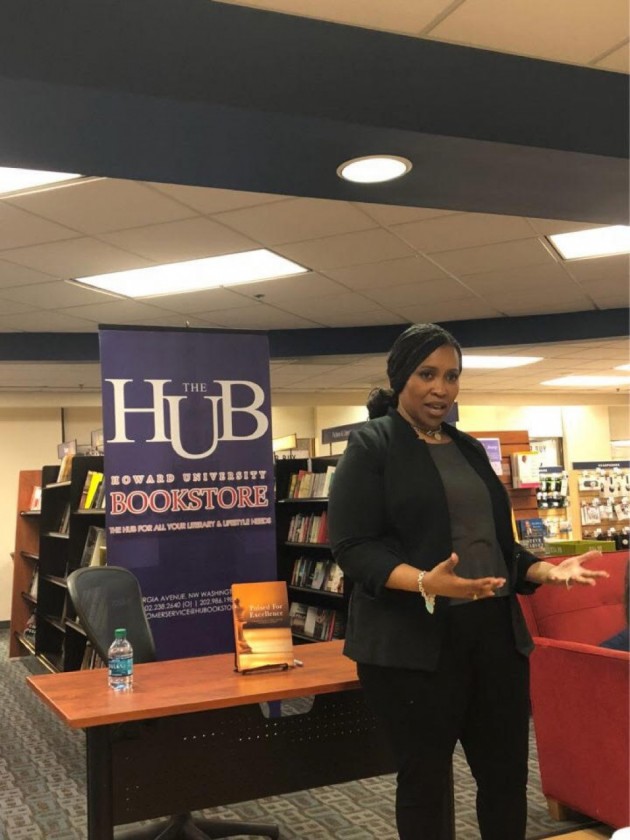

WASHINGTON – Touré took over the District. The pop culture journalist and critic hit Busboys and Poets and Howard University Bookstore to sign and discuss his new book “Who’s Afraid of Post-Blackness: What It Means to Be Black Now.”

Touré left some with a better understanding of the term “post-blackness,” and others still confused, but most importantly he sparked a conversation. He said he included the questions asked to the 105 people he interviewed for his book, because he wanted to get people talking about it. And that’s exactly what people did.

Thelma Golden, director of the Studio Museum in Harlem, and Glenn Ligon, conceptual artist, coined the term post-black in the ’90s.

“Being an artist who happens to be black is liberating; being a black artist is confining,” Touré said.

He uses the term to describe the complexity of being black in the age of Obama. Post-blackness does not mean post-racial, Touré stressed.

“There are 40 million black people, so there are 40 million ways to be black,” said Toure, quoting Henry Louis Gates, an interviewee from his book.

Over on 14th Street, on Wednesday night, Jonathan Capehart, a writer at the Washington Post, joined in the discussion. Stirring the minds of the audience at Busboys and Poets, Touré read an excerpt from a chapter in his book, “The Most Racist Thing That Ever Happened to You.”

He read from the voices of comedian Chris Rock to Yale professor Elizabeth Alexander and the irreverent tales about their encounters with racism today – which many of them concluded is not something you can vividly describe, or something they may not have ever known happened to them.

“Racism is more subliminal, subjective and subtle today,” Touré said said. With racism today blacks must choose their battles, he said, giving the example of Rick Perry’s “Niggerhead” Ranch to roll your eyes about, but the Troy Davis execution to stand up for.

But, a shared history and a past of racism are the only things that Toure said brings black people together.

“We decided that we are a community, but what exactly is the glue?” Touré asked. “There is no value system that black people share.” He continued, “I think less than ever there is a consistent black experience, different from our parents and grandparents.”

In this day and age, black people have the ability to be both communal and individualistic, Touré said.

“The Civil Rights that they [black people] fought for, we have them now. Unity alone is not going to supercede the glass ceiling,” Touré said. “Racism is not the same. The battle can’t be won with the same tactics as before.”

Ariane Inkesha, who moved to Washington, D.C., from Gambia less than a month ago, found that she could not directly relate. She didn’t notice that she was different, in terms of race, until she visited France, but moving here she has noticed that no matter where you are from, people see you the same – black.

“The way we experience blackness is very different,” she said. “I didn’t realize I was black until I came here. We don’t have a conflicting relationship with White Americans.”

Haitian-American Bianca St. Louis agreed. When she first moved here, she didn’t understand why race and self-identification was such a big deal. She asked Toure how members of the Diaspora fit into the concept of post-blackness, which focuses on only blacks in America.

“We need to have a more ‘diasporic’ mindset to understand that you are my brother and sister just as much as anyone else is,” Touré said. “If you are from Ghana our boats just happened to stop at different times.”

At Howard University, where alumnus Riley Wilson joined the discussion on Thursday, Touré recalled a time at Emory University in Atlanta when a black linebacker told him, “Shut up Touré! You ain’t black.” This moment pushed him to define his own blackness and eventually write the book.

“They [black whistle-blowers] have a narrow vision of what it means to be black. When you go with that they say, it is twisting history a lot of the time,” Touré said.

Some audience members, like Howard alumnus Michael Tomlin-Crutchfield, thought Touré was defining the term blackness from the stereotype of “acting white.”

But, Mike McIntyre thought differently.

“Post-Blackness is just a new term to talk about the struggles that we’ve [black people] always had in terms of self-identification,” McIntyre said.

Touré in His Own Words

On Music and Post-Blackness:

“We don’t have a universal massive figure like James Brown or Marvin Gaye. The cultural distribution system doesn’t allow figures like Beyoncé to reach us culturally. Now we have so many black experiences that it is hard to find a centralized one”

On the Work World and Post-Blackness:

“Your ability to get ahead is at stake When those things are at stake then perhaps playing the game is more valuable.”

On Using the Word African American:

“African American, linguistically speaking, is a mouthful and genealogy speaking it’s not accurate. The word black has so much power.”

On Performing Blackness:

“We all have the ability to modulate, given the different people we are talking to. We are always performing for somebody, so there are multiple ways of performing blackness.”