By Maya King, Howard University News Service

A healthy patient-provider relationship requires a strong element of trust. Patients trust their doctors to give them the treatment they need when they are ill, just as doctors trust their patients to follow his or her directions so they won’t have to return quickly or in worse condition. These are the basic rules of medical care and they have applied since before the drafting of the Hippocratic Oath.

In the District of Columbia, a potential breach of trust has occurred between some patients and healthcare providers. When Northeast Washington’s Providence Hospital made plans last Spring to close permanently, hundreds of Ward 5 and 7 residents lost access to affordable hospital services close to their neighborhoods. Similar numbers of doctors, nurses, medical technicians, and support staffers also lost their jobs. Providence’s closure was rooted in an apparent lack of resources—yet, it created what many Northeast residents saw as a clear break between the hospital itself and those who needed its care.

“It upset me because I figured that with Providence closing, that’s gonna mean that Howard University Hospital and the Washington Hospital Center are the next closest hospitals,” said Jean Johnson, a former Providence patient and Ward 5 resident. “But when I attended a hearing, [Howard University Hospital and Washington Hospital Center representatives] said they could not handle any more emergency cases.”

Providence Hospital officially ended its acute care services in December 2018. Citing a near $23 million financial loss over the last three years and commitment to moving in a “new strategic direction”, representatives from Ascension, the Catholic-owned company that runs Providence, said in a statement that the 283-bed facility would officially close its doors by April 2019.

“The community felt very betrayed,” said Emily Lucio, a Ward 5 Advisory Neighborhood Commissioner. “They felt as though no one came to them to say, ‘business isn’t going well, we’re looking at closing.’”

Now, other medical centers are taking up the task of providing for some of Washington’s neediest patients. Howard University Hospital, known historically as a safe place for low-income black Washingtonians to receive quality medical care, is chief among them. Since last year HUH has added extra bed space, opened new care units and hired additional medical staff (a number of whom were former Providence employees) to accommodate the sea change. But doing so has been a heavy lift for the hospital, which is entering its third year of financial surplus after spending several years in the red.

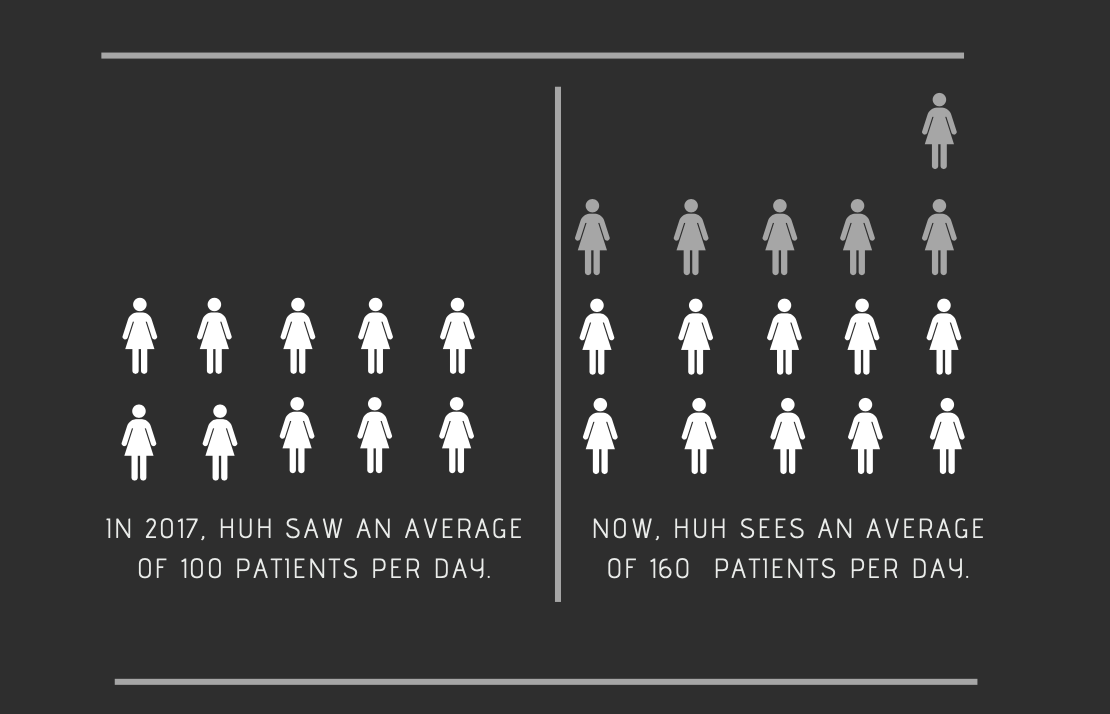

“Right when Providence even made the announcement, we saw the bump up [in the number of patients],” said Sandra Mavin, HUH’s Assistant Chief Nursing Officer. “We had to get more staff, we had to get more resources, more supplies, more everything, to accommodate.”

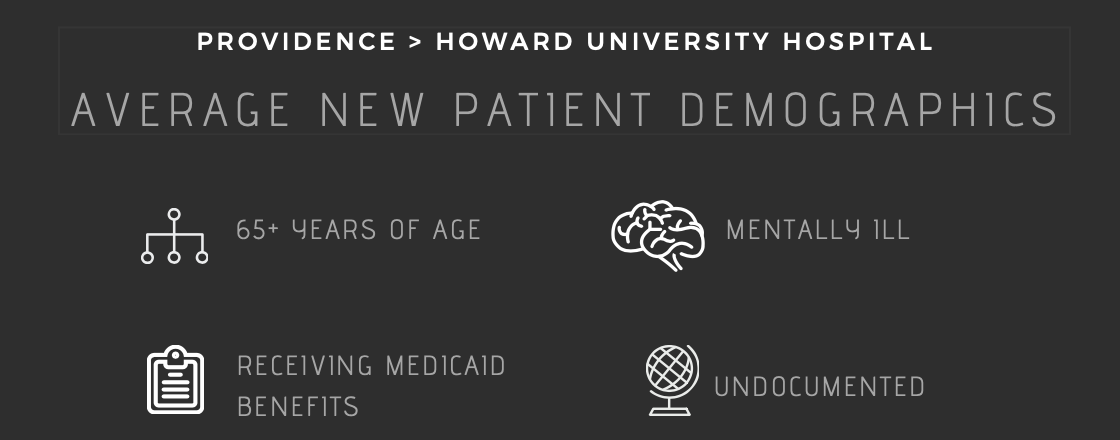

As a non-profit healthcare facility, Providence provided care to patients that many other hospitals were reluctant or unwilling to serve, due to the fact that a majority of them were uninsured or received Medicaid benefits. The low reimbursement rates attached to these patients made it difficult for hospitals to break even financially after providing care.

In a public response to Providence’s closure, Howard University president Wayne A.I. Frederick, who is also on staff as a surgeon at HUH, affirmed the hospital’s role in continuing to serve any and all patients, saying that the university medical center “remains committed to bridging any resulting service gaps and providing care to serve the District of Columbia community.” For HUH’s leadership, bridging those gaps has required immediate, extensive, action.

“That means meeting patients and individuals where they are,” said Dr. Shirley Evers-Manly, HUH’s Chief Nursing Officer. “We know we have a lot of patients with diabetes and sickle cell, so we really want to be able to provide patient-centered and family-centered services for those patient populations.”

It also caused them to look more closely at what public health providers refer to as “social determinants of health”, or the socioeconomic factors impacting one’s quality of life. A new wave of patients who struggle with substance abuse, homelessness and mental illness have quickly folded into HUH’s patient population over the past year. Some are also undocumented.

“Those are the patients who, when you think of the Catholic hospitals and sisters of charity, [providing services to them] was their mission,” Evers-Manly said.

Now that the city is without a large enough hospital center to fulfill this semi-charitable role, a number of DMV-area medical centers are at a moral and financial crossroads in determining how to best care for patients without completely turning them away.

“With the new diagnostic-related groupings system, the goal is to get the person out [of the hospital’s care] within five days,” Evers-Manly continued. “But if you have somebody who comes in your hospital and they’re here because you don’t have a place to send them or their families don’t want to take them back in, it becomes a problem.”

“Are we a ‘charity hospital’? No, we’re not,” Mavin said. “But are we gonna close our doors or not accept patients that need us? We’re not going to put you out if you don’t have anywhere to go.”

Some patients, however, may not find the inconvenience of Providence’s acute care closure surprising. When Providence closed its maternity ward in 2017, there was no mention of it on the hospital’s website or at the hospital itself. The change was so sudden that some expectant mothers did not learn of it until arriving at the hospital already in labor. In response, HUH opened two new units and expanded its maternity ward to meet the patient increase.

HUH’s response to Providence’s maternity ward closure represents an early effort to pick up where a fellow healthcare provider had fallen short. In 2018 the hospital began expanding its maternity ward through the construction of a new wing that will increase the hospital’s birthing capacity from 900 to 2,000 deliveries annually.

Johnson, who went to Providence seeking care for herself and her husband, said they both have had to adjust to the closure of their hospital of choice. The couple goes to Washington Hospital Center now because it is where their doctors have decided to practice. But longer wait times and potentially lower quality of care are genuine concerns for both of them, who are part of the community above the age of 60.

“The aging population have been long-standing members in this community and supporters of Providence hospital,” Lucio said. “Many of whom don’t have reliable transportation to get to other areas of town, so they’re a top priority.”

As a resident of Ward 5, moving from Providence to the Washington Hospital Center adds an extra ten minutes to their commute by car and 30 by bus. It could be the difference between life and death, though, as she and her husband used the hospital primarily for emergency purposes.

“It just kind of frightens you to know that you aren’t gonna have any medical service close by,” Johnson said.

As a result, HUH’s emergency patient population has increased by an average of 50-60 additional people per day. Unexpectedly, the number of walk-ins has far exceeded the number of patients who arrive via ambulance. Over the last year, the average length-of-stay for patients at HUH increased by an entire day.

Former Providence employees also are facing a new reality with the hospital’s closure—since December, at least 800 nurses, technicians, and administrative staffers either lost their jobs or were put at risk of losing them. It amounts to a major community job loss that could have comparable economic consequences.

According to Elizabeth Falcon, executive director of D.C. Jobs with Justice, Providence’s closure was not very widely known in the community it served. She and her team lobbied local leaders and media outlets, hoping to draw more attention to the issue and fight for a way to keep the hospital from closing so abruptly and putting people out of work so quickly. Employees, too, had the same concerns as patients.

“Folks were worried about long trips across town to get to an E.R., plus Washington Hospital [Center] has long waits,” Falcon explained. Jobs with Justice, she continued, aimed to use D.C. government resources to “hold the hospital accountable to the needs of its community.”

Howard University Hospital has, in turn, hired a small number of former Providence nurses, technicians and administrative staffers, according to Evers-Manly. They even held job fairs at locations in the Providence neighborhood.

Ascension Health, the company that owns Providence, controls a national network of hospitals in 21 states across the country. According to its website, it is the largest Catholic-run health network in the U.S. It is also no stranger to closures. In late February, Bay Medical Sacred Heart, a Miami-based hospital that is part of the Ascension network, announced that it would be closing its maternity ward due to hurricane damage.

In response to the negative community response to their closure announcement, in late February Providence officials announced plans for the construction of an urgent care center and health village on the hospital’s Northeast campus. While it could offset a large number of Northeast residents looking for semi-immediate care, to some, it is little more than a public-facing effort to clean up a hasty closure.

“They seem to be piece-mealing this process,” said ANC commissioner Sandi Washington during a meeting in late March. “I just hope this is more than just a head nod.”

The D.C. Department of Health did not immediately respond to a request for comment. Representatives, however, have publicly pointed to the construction of the new East End hospital to be built in Southeast Washington. It’s good news for some Ward 7 residents, who feel that low-income black D.C. citizens have been caught in the middle of a public health crisis for years.

“Ward 7 is in the middle of a food and health desert,” said Tyrell Holcomb, Chairman of Ward 7F. “There are very few resources that for the last 10-15 years or so that have been dedicated to improving the quality of health and the quality of life for residents.”

Holcomb said the closure of Providence added several additional barriers to care for residents of his neighborhood. Travel times, wait times and varying qualities of care were all issues he listed as part of the average patient experience. In turn, he said, some residents put off going to the hospital altogether, even if they needed to. It prompted Holcomb to support a resolution that pushed up the target date for East End Hospital from 2023 to late 2021. East End is on track now to be funded early so it can begin construction as soon as possible.

“It’s not one issue necessarily impacting the community,” Holcomb said. “The lack of a real healthcare system East of the River is an issue that impacts all of us.”

Ward 5 commissioners agreed during a meeting in late March to sign a letter of support for the medical village, citing the positive impact of having at least some medical care in their neighborhood. According to Ascension representatives at the meeting, as soon as the hospital receives the required signatures, it will begin the process of opening the medical village—which will function like an urgent care center and also provide ambulatory services—in late May.

In the meantime, Howard University Hospital and others are continuing to provide care to as many patients as it can using all of the resources it has available.

“We’re caring for the patients,” Mavin said. “We’re strapped, but the patients that are coming to us, we’re caring for.”

This story originally appeared in the 2019 Capstone Newslab Project The Black Print