By Alexis McCowan, The Undivided For Howard University News Service

A butterfly flaps its wings in Alaska and causes a hurricane in New York. This is the concept of

COVID-19 for a child with autism according to Dr. Shameka Johnson, a speech specialist.

The coronavirus has turned every human’s life upside down and added a mask to every possible

equation. The dynamics of daily life, hospitals, and schools has been dramatically altered. These

changes have been difficult on every human being, but pose unique challenges for autistic

people.

Kristel and James Minnock are the parents of Jesse Minnock. Jesse is 13-years-old, an only child

and he has severe autism. They currently reside in Ventura County, California. He is described

by his parents as a 13-year-old toddler when it comes to his mannerisms and behaviors.

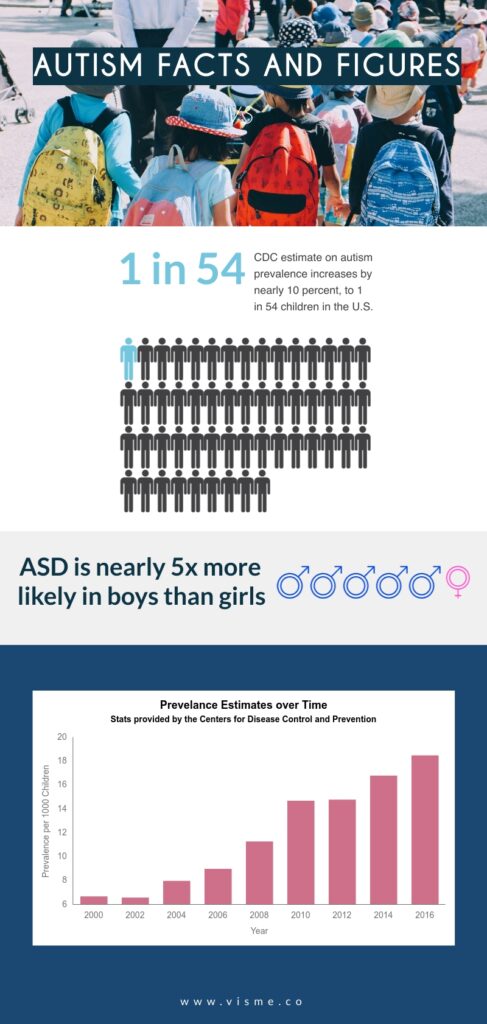

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that 1 in 54 children in the U.S.

has autism. The prevalence is 4.3 times higher among boys than girls. In 2018–19, the number of

students ages 3–21 who received special education services under the Individuals with

Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) was 7.1 million, or 14 percent of all public school students.

Among students receiving special education services, 33 percent had specific learning

disabilities.

In March, James said Jesse’s school administration went from “hey, school tomorrow to

nothing.”

There were few packets that were sent out to families and there was minimal communication

from Jesse’s school.

According to James, Jesse doesn’t do well with transitions so they tried to provide normality for

their son at the beginning of the academic school year. Before the pandemic struck, James said

their most common day involved him going to the office and Kristel, his wife, working from

home as an adjunct professor.

They do this same exact routine every day.

“I’m sitting in my car until I can go home so that he thinks I was at work,” he said. He completes

his work from his car.

In terms of school, Jesse is in a virtual learning environment. He has one main teacher and there

are a few parent educators that participate in Zoom classes as well. He spends about 40 minutes a

day in his classes.

The transition into virtual learning was a strenuous one because Jesse loves school. Kristel said

he kept requesting to go to school; physical school.

According to an article from Spectrum News, many autistic people are being cut off from day

programs, school services and in-person medical appointments.

Children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) develop at a different rate and don’t necessarily

develop skills as typically developing children. Children with ASD can struggle with focus,

attention, transitions, organization, memory, time management, emotional control and

frustration.

“He would try to get his backpack, he would ask maybe 50 times in a minute for the bus and I

just kept saying it’s not coming, it’s not coming,” Kristel said.

“He [Jesse] would reach a level of frustration where he did get pretty upset and self-injurious. He

usually starts with banging his head on the table, banging his head on hard surfaces and then he

may start hitting other people,” she continued.

Psychologist, Dr. Sharon Thomas said children with autism are up against different challenges

Psychologist, Dr. Sharon Thomas said children with autism are up against different challenges

during coronavirus.

“Kids have anxiety about what COVID means and some difficulty adjusting to these new

routines that unfortunately change all the time. People that they were used to seeing regularly,

they don’t get to see anymore.”

“There is some difficulty with missing friends, although they’re expressing it in a way that looks

more like defiance and tantrums,” said Thomas.

James also said that on typical days before Covid-19, if Jesse would have an emotional outburst

there would be several trained professionals that would know how to diffuse the situation.

During the pandemic, Kristel acts as the trained professional.

The main support that the Minnocks receive comes mainly from within their household.

“People in our shoes, their social circles get very small very fast,” said James.

The Nelson family is also impacted by the pandemic and the changes in the environment. Akiko

Nelson, mother of Luke Nelson has been focusing on helping her son become as independent as

he can be. Luke is 21-years-old and has severe autism and limited communication. In March, his

school announced that the school would be closing and Luke had a difficult time with the

transition. Akiko decided to give it a try but his behavior was getting more aggressive.

After three days on Zoom, Akiko realized that virtual learning was not a good fit for her son.

“Zoom was putting more demand on him.”

Luke identified school as a place where he could socialize,but that aspect was not apparent to

him during virtual learning. Teachers unconsciously paid more attention to verbal students and

this created frustration for Luke.

“It’s natural for staff and teachers to gravitate towards the ones that can communicate and

conversate,” said Akiko.

Since the school was only offering Zoom, Akiko made the difficult decision to put a “pause” on

his education needs.

Akiko said, “It was only creating stress for Luke; there was no reward.”

One of the many challenges the Minnock’s face is not receiving occupational or speech therapy

at this time, which is an essential part of Jesse’s individualized education program. Speech

therapy for example is important because Jesse is non-verbal and he needs to know how to

communicate with others.

Without that “he is not getting a real education at all,” his mother opined.

Jesse’s transition to early learning has not been entirely effective and his father sees it as

performative.

“What we are doing right now, to me, is theater. Where we are all acting like we are doing

something that will help Jesse but it’s just theater; nothing is actually happening,” he said.

The virtual set up he believes for children on the autism spectrum is a result of a lack of courage

and communication.

“Where the courage would come in is at the federal, state and local level to have the courage to

say, “we can’t teach your child in the current environment, with whatever is going on, we can’t

do it,” said James.

“This is Luke’s last year because he is aging out and we decided to create a program to focus on

more self-help skills rather than doing academic skills,” said Akiko.

She continued, “The goal for us is to get him to reach a point where he can actually do it [tasks]

on his own. It’s more about making him independent in these little steps, like shaving, bathing…

and pouring his own milk.”

Researchers at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health contributed to a new U.S.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report that finds the prevalence of autism spectrum

disorder (ASD) among 11 surveillance sites as 1 in 54 among children aged 8 years in 2016.

“They [autistic children] each have unique challenges depending on what level of functioning

they have and what other challenges they have in addition to autism,” said Thomas.

“Some of my clients have autism as well as Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder.” Right

now those clients are having “the most difficulty staying focused, staying on task, remaining

engaged and given the distance between the teacher and the student it’s been harder to keep them

engaged,” she continued.

People with autism often have anxiety and struggle with small changes to their schedule. The

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke reported that people with ASD thrive off

of routines and when there is the slightest change or disruption can pose a challenge. The result

of these changes often emotional outbursts that have the potential to get violent.

“There is a risk in regression not just in their difficulty practicing and maintaining their social

skills, but a tendency to withdraw into themselves and to go back to being more rigid in the

things that they like to do. They may want to focus more on iPad time or video games or the

things that are individual activities that are at times easier than keeping up with a social

interaction with a peer,” said Thomas.

Psychologists spend months preparing autistic clients for different transitions in life, but no one

could prepare for the coronavirus.

Speech pathologist, Dr. Shameka Johnson talks about the importance of educators and clinicians

during the pandemic. She said that the responsibility to adapt to the changes lies with educators

and clinicians.

Johnson said the pandemic has the potential to stunt children with autism’s growth but “it isn’t

the sole indicator.” The real indicator is the ability of the educator or the clinician to engage the

child.

“If there is a disconnect in the service or the education, that’s the biggest indicator of the child

regressing or not retaining information more so than the pandemic, because life happens all the

time,” she said.

Johnson said there is still a job to be done, whether the world is in a pandemic or not. clinicians

and teachers have to prepare themselves to best support children with autism.

“It’s really about how we respond to life happening. If we’re not prepared as the professional on

our way to address and adjust and meet the needs of the child that’s going to be more of an

impact then the actual pandemic.”