The Educational Saga

Of an American Family

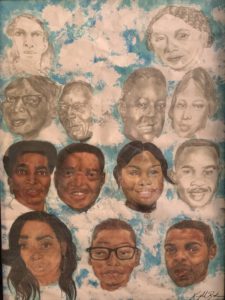

What has been my family’s experience and contribution to education in black America? I thought back to my maternal grandmother, Vera Webster, telling stories about going to school in the South. My paternal grandmother, Rose Miles, also grew up in the South and attended Tennessee State University (TSU). But before I could understand their responses and memory, I had to see where they came from and what came after them — perhaps finally talking about myself to then compare and contrast our educational experiences. I began my research by conducting interviews and looking into the archives and records of a few HBCUs. To do justice to their experiences of struggle and triumph, I’ve broken their stories into sections by name, time, and place along with updates on the following generations.

Vera Webster – Greensboro, Alabama, in Hale County

Early Years and Grade School (1942-1961)

Q: How would you describe your educational experience in black America?

A: I didn’t have all the means I should’ve had to get an education. During my time, we didn’t have time what we needed. The white kids had better books, and we were separated; that was a hindrance for us getting what we wanted. Black kids didn’t go to college [in my town] maybe 10 out of 500. We didn’t get prepared for college. Only a few parents struggled to send their child to college, the rest didn’t go. There wasn’t any grant or financial aid offered to us – although my cousin, Sarah Lee, did go to either TSU or Alabama A&M, and few sisters of a friend I knew.

Q: What are some of the things you remember about each period of your education from elementary to high school?

A: Well in elementary, I started at a school called Saint Luke. First, second, and third was taught by Miss Jessie Bell and fourth, fifth, and sixth was taught by Miss Ellis. It was two rooms to this little school, and they’d teach each grade for a few minutes each. After awhile, they closed that school and sent us uptown to another school called Stephen Memorial School. I remember when we get flu shots, they would vaccinate the white kids first and then bring the same needles to us. When they came, kids would be all over the place- running. The needle was dull and it made our arms stiff and swollen and our arms bled. The Lord took of care of us!

Q: Was it a different experience going to school and growing up in the South and, if so, in what way?

A: Yeah, it was different. Kids didn’t have the clothes they needed to go school. Segregation was the problem–we had no rights! No one told us anything; we had to pay to go to public school. You had to pay when you got to the next grade, but the whites didn’t. My brother, Ted, was working at a drugstore and they kept getting calls from white folks saying they were gone move their business if Ted didn’t get fired, because Ted had been demonstrating for civil rights. Said they didn’t want to do it but they had to let him go, and he told them it was all right ’cause he was going up North. That store closed a few years later.

Q: Were whites intimidated by educated blacks in your area?

A: Yeah, but those black people might have had a better income and so had more material things but no respect. Most of the black teachers were told to vote Republican to keep their job, so that’s what they did to protect their job.

Q: What were some of the ways you learned outside of school?

A: My mama taught us how to read and write. We all knew how to read and write our names and some times tables. We knew how to write complete sentences with the right punctuation before we started school. We didn’t have to start from scratch; we already knew the stuff before we started. She taught us by having paper on the wall and asking us what the things she hung up spelled.

Q: As a child or teenager did you notice any big difference in your schooling versus the whites?

A: We didn’t know exactly what the whites was doing. We knew they had good buses that would let them off right at the house if it was raining, ’cause they had pavement, and we had dirt roads. Their buses had heat, and ours didn’t. See, they would give the old buses to us when the white kids got a brand new yellow one, so sometimes the windows would be busted out on ours. The principal of our school was black. His name was Mr. Fredd, and the white superintendent was named, Mr. Raimi. They came up with the idea to charge 7-12th grade children tuition — about $2 a child. There were 11 of us, and Dad struggled to pay it. So, sometimes he wrote Mr. Fredd a note saying he’d have it soon; it was an IOU. Come to find out Mr. Fredd and Mr. Raimi were splitting the money; they were getting from the black kids paying for tuition, books, lunch.”

Q: What was your parents’ education, and what time period did they live?

A: They didn’t have really have one. My mother stopped in the 10th grade, and I think my dad stopped in elementary. Mama didn’t drop out; she just couldn’t go. Ma and Dad could read and write though. My dad was great at math! They grew up during the early 1900s.

Q: Did your parents stress education?

A: Yeah, they did, but Dad not so much but Mama really did. But we had to stop and do crops for a while. During the late ’50s early, ’60s, the government stopped that so we had to go to school instead of doing crops and start when we were supposed to and that was the best thing. Before that, we started late about the last of October or the first of November, because we had to finish crop season. We had to borrow a friend’s book, but when you did that, you had to do your homework and theirs, too. (Laughs)

Q: What was your grandparents education?

A: My grandmother Eliza could read and write. Grandma Elizabeth couldn’t read or write, but she had lots of common sense! She lived off common sense. The whites folks thought she crazy, ’cause she would talk back to them. I don’t know grandfathers; they died before I was born.

Q: What did your grandmothers teach you?

A: My mother’s mother died early. Grandma Elizabeth didn’t teach much except how she made certain food and to “stay out of southern white folks way; they get you into trouble.”

Q: What are your thoughts on education, and does being black influence how you feel about it?

A: Every child needs one because the more you have the more free you are! It might — that education is best when you can go to college. In my day, coal mine and railroad workers could afford to send their kids to school, but they’re better programs now.

Q: Any additional comments?

A: I wanted to go to college but it was just hoping in vain. When I finished high school in ’61, that was it. I wanted to be a registered but I had a son and I started working and never did it. But I was so happy when my daughter Krissy went to Howard, ’cause she was the first of my three that finished and a first generation college student. I didn’t know much about Howard, but I’d heard it was a good school. But I never thought I’d have a daughter and grandson go there, and that’s a joy to me.

Paternal Grandmother: Rosie Miles, Greenwood, Mississippi, and Memphis, Tennessee

Early Years to College (1945-1967)

Q: How would you describe your educational experiences in black America?

A: It was very exciting. It put me on the path to acquire meaningful academic knowledge and develop social skills needed for outside of school culture. It taught me that sharing was very important in the world. It could be from offering an extra piece of cake to offering your knowledge of a subject. We came to Memphis when I was four months old. It’s been home ever since. My education was started in Memphis Public school system at Manassas High School, that housed grades one through 12. We were separated by floors: high school, third floor; junior high, second floor; and elementary, first. You were not to be caught on the wrong floor without a teacher’s pass. The band room, gymnasium and auto shop were in adjoining buildings.

Q: What are some of the things you remember about each period of your schooling?

A: I didn’t attend kindergarten. It was not a part of public school. Private homes and babysitters provided some basic learning skills. My family thought I was ready for 1st grade, but I did not know my “ABCs.” It only took sending a note home and an overnight drill by my father to catch up on five years of work. My brothers and sister served me a severe warning to never let that happen again. We had a family history in the school, so they were embarrassed when confronted by the teacher. Junior high was a little tense. Five teachers out of seven were males; therefore we had to always come correct. But, they were good teachers and I really enjoyed their classes. Everybody had to participate right or “don’t know.” Senior high: Miss Popularity, Homecoming Court, social clubs in school and city wide, and presented as a debutante 1963. I also wrote a weekly article for the Memphis World newspaper.

Q: Was it a different experience for you going to school in the South and, if so, in what way?

A: I didn’t have anything to compare it with until I started my career as an educator in the north and watching how the students were programmed and placed was very interesting. We were more or less placed as a whole and taught as a group.

Q: Did you have what you need in school in terms of books and supplies, or did it seem the white students got the best?

A: White students definitely got better treatment. We were totally segregated. They passed the white school’s discarded books to the black school when they got new editions. We were responsible for 90 percent of our supplies; that’s where sharing played a big part.

Q: Were whites intimidated by educated blacks in your area?

A: Segregation was a way of not accepting black intelligence. So we have white flight back to the outlying areas surrounding the city. Therefore, their children will not know how intelligent blacks are, and it keep going in circles until this day.

Q: What were some of the ways you learned outside of school?

A: We had church activities year round. Memphis was known for it — great teenage social clubs around the city. You were given the opportunity to meet other students around the city. The sponsors were from sororities and fraternities as mentors. We had competition among the various clubs for honors and recognition.

Q: As a child or teenager did you notice any big differences in your schooling versus the white?

A: We were shut out totally but knew things were not the same — especially using discarded books and old gym equipment.

Q: Parents’ educational background and their time period?

A: My father attended Alcorn State University for one year. My mother only attended up to the 10th grade, 1919-1921.

Q: Did your parents stress education.?

A: They knew that education would be a stepping stone for preparing me for an aspiring adult future, while stressing discipline and responsibility. I only missed three days from the first to 12th grade.

Q: Parents’ and grandparents’ education?

A: My paternal grandparents were master carpenter and eighth grade education. My maternal grandparents were a farmer and seamstress. My maternal grandmother’s mother was Mahalia York Hudson. She was an out-of-wedlock white baby, and they gave her to the help, the Yorks, to raise. Her white family paid for her to go to Tougaloo College where she majored in home economics. She married a Native American, Joe Hudson.

Q: What did your grandparents teach you?

A: They put lots of value on behavior and manners. I was taught how to sew and choose fabric. How to work as a team while doing chores around the house.

Q: What are your thoughts about education, and do you think being black influences your thoughts on it?

A: I am very thankful that I was one of God’s chosen to be a part of a group that helped me develop inner growth and knowledge to develop into a responsible individual. Yes, because it has exposed me to things more important than competing with other races. I realize that I could also make contributions and share with my people as windows to joy.

Q: Were white southerners involved in any part of your education?

A: Yes, they were the wind in my back. Once my vision became clear, I have never stopped moving forward with as many as I can bring along to be a part of this educational journey. I have been in situations that nothing brought me out but education and God.

Q: Any additional comments?

A: Thanks for giving me the opportunity to look back over parts of my past. My school days were my anchor, and for that, I am thankful. Parents and faculty continue to stand and rally for the students. We have a rich history of scholars and respectful citizens that have achieved great accomplishments around the world. A lot of those greats still serve as mentors today at Manassas. This is 20 + year for a school wide brunch given every year in Memphis, the 2nd Saturday of May with 1,000 plus in attendance. UNITY. I should mention I regret not listening to Mama about our family history, because she really was the family historian I wish I would’ve at least tape-recorded. That’s one of my greatest regrets.

Honoring My Family’s History and Memory

When I was seven years old I saw Alex Haley’s Roots miniseries on TVOne. I was enthralled by the idea that a person could find their ancestors before slavery. So I started doing research into my family history. My grandmother knew who her grandparents were, so that was an easy start, but I became interested in seeing if I could break the barrier to before 1800.

My cousin and I found that our oldest ancestor was born c.1831. Her name was Eliza Gause, born in Virginia in the year of Nat Turner’s Rebellion. Eliza was sold into Alabama early in her life enough to say later that she didn’t remember her mother and father. She married a man named Ed Johnson and had one son with him, also named Ed.

In her old age Eliza Gause was widowed and went to live with her son Ed; that’s where she was found in 1910 at age 79, when the census was conducted that year. It was said that Ed was incredibly strong: once there was a shed that had caught on fire and Ed lifted up the flaming shed to get the animals out.

Her son married a woman named Ellen and by 1875 had a daughter named Eliza Ann, along with three other daughters. Eliza and Dan Holley II married on January 7, 1901 and had four daughters, one of which was my great grandmother Adell. They also had a son whose name has been lost over time. Dan Holley II parent’s, Dan and Lucinda, married some years after emancipation on December 7,1881.

Adell was a faithful member of Greenleaf Baptist Church where she was the secretary of the senior choir from the 1940s until her death in 1977. Adell married Albert Webster on March 22, 1922. Albert was light skinned with gray eyes. His father named Link, was about three when slavery was abolished. Albert’s mother was named Elizabeth

Shephard. There’s an old story that may be apocryphal. While in the field sharecropping one day, a white man watching said something to her along the lines of “Get back to work,” and Elizabeth responded, “You get down off that horse, and I’ll beat you until you shitty as a bull.” The white man raised his eyebrows and said, “ Oh get on way from Lizabeth, you crazy”

Adell had eleven children, one of which was my grandmother Vera. Vera had three children, the youngest of which was my mother, Kristen. All that culminated in her being the first generation college student on her mother’s side. Albert and Adell lived in a place called “the quarters” until the late 30s where they moved to a location called, “Picken’s Place.” Israel Pickens was the governor of Alabama from 1821-1825; he along with his brothers and nephews owned most of the slaves in Alabama, and my family may have worked for one of the Pickens. The Pickens sold one of the properties to Lewis Lawson, the man my great-grandfather Albert would sharecrop for until the 1960s when Lawson died.

Vera married a man named Otis Williams on August 7, 1976. The Williams family goes back to 1816 from Tennessee. Richard Williams was born in that year in Tennessee, while it was still written in maps as “Indian Territory.” Richard Williams and Lucinda Fitzgerald had a son named Frederick in 1840. Frederick jumped the broom as a slave with an unknown women who died before she obtained emancipation. They had children who later ended up in Chicago whom we last saw in 2000. Frederick married a much younger woman named Marthie after emancipation. He continued to have children into his 70s, one of which was my grandmother Orell. Frederick lived to be 107, according to his grandchildren, he was still running after them and lifting them high over his head at that age.

Orell had a son named Otis who moved to Flint in 1950 the year after the death of his father, Raymond. Orell lived to be 93 and died in 2006, I still have faint memories of her. Otis died in 2009. Leaving his sons, daughters and grandchildren behind. One of the last things he did was vote for then-candidate Barack Obama. He smiled as he walked away from the booth. He watched the inauguration on TV that January he said, “I’ll be- I never thought I’d see a negro President.” One of his daughters told him the word was “black” now. He shrugged, all he cared about was the man who had just been sworn in.

The descendants of slaves, sharecroppers, and auto-workers, I sit here at Howard University. As I sit I often think of those who suffered before me, and they seem to me to be saying, “You must go on, you must press forward, you must finish.” So that’s what I intend to do (and in that way) honor their memory. – Jaylen Williams”

The Saga Continues

So after those two interviews a few common themes became clear to me that there was a common trend of segregation being detrimental to the young lives of my grandmothers. For them it became an enemy though not chattel slave they are treated as an inconveniences and had to that they too, were America. You’ll also notice the trend that they were both given hand me downs and hate segregation with a vehement rage. So though we know they’re here to tell the stories but what happened up to the present day.

Vera Williams (1961-Present)

Vera married my grandfather, Otis, who’d gone up to the ninth grade, according my aunt Angel, “He said, “‘I’m done with school they can’t teach me no mo’. I’m going up to Flint and get me a job in at General Motors like my uncle.”’ Otis’ brother, Clyde, went to Howard also graduating from the School of Dentistry. Vera had three children, a son and two daughters, Angel went to Ferris in Michigan and considered pledging with the Iotas. Her son, Carl, went to a school in Columbus, but when Vera was laid off he didn’t feel right using their money so he went to a community college in Flint, called Mott. He felt he was a financial burden, Angel became physically sick and had to return home she did go to Mott and Baker. My mother graduated from Howard in 2005. On why she chose Howard she said, “From the time I watch “school daze” and heard the “doing the butt” song by E.U., I wanted to go to an HBCU. I’ve always been inspired by black unity, weather it’s with love, sportsmanship, or entrepreneurship. I love all things Black. With age and maturity I began to explore what I wanted for myself. What college I wanted to attend, and by the time I was a Junior my top four college choices were Howard University, Xavier University, Ohio State, and University of Michigan-Ann Arbor. The best of both worlds at the time…to me. The more Jet Magazine’s I read, and the more I became aware of the elite alumni that had previously attended Howard, the more I knew I wanted to be apart of that type of greatness. Phylicia Rashad pretty much sealed the deal for me. Cosby show was my era, and she was everything to me! (My mother shared, I think her sense of style and elegance as someone who was both book smart but wasn’t street dumb. Claire and mother had a dry wit about them being mothers) My second semester of my senior year of high school I became pregnant with who we now know to be Jaylen. Although my dreams of going away to college had to be postponed, it was very important for me to not give up on my dreams. I pondered back and forth with the idea of going miles away from my child just to attend a university I feel in love with as a child. Despite the judgement and naysayers, I decided to pursue my dreams and I’m so happy I did. Howard University shaped me into something I know I never would’ve received from a predominantly white university. Howard gave me confidence, tenacity, and assurance of myself so that I could be the role-model I thought my son needed to see.

So we go from limited education but common sense sharecroppers miles away from Washington and only a faint notion of a dream for family to be able to go to such a place to a legacy Howard University student. We see through these that the future and hope for a better day was in the mind of all the people aforementioned but what happened to Rose?

Rose married my grandfather, Hardin Thomas, a Alabama A&M graduate. She too, had three children. Twin boys and a daughter. Alaina went to Hampton and the twins went to Morehouse. On Morehouse my dad, Ainsley, said, “The reason I went there had a lot to do with tradition, I had to attend summer school to go there so it presented a challenge for me and I loved the fact MLK went there. The sociology department was cool and that’s what I majored in. Atlanta is a great cultural place and that sealed the deal for me.” His twin brother Ash opined , “There was this mystique and sense of pride Morehouse men always displayed. I chose to attend Morehouse because it offered me the promise of being molded into a scholar and a renaissance man who was sensitive to the needs and sufferings of others. It would seem HBCU’S are in my blood. Everyone had a common goal to immerse themselves in the back community as it were. Even that the white relative of ours who was not black but because of the circumstances surrounding her birth grew up with the black experience and became adopted into the black community in Mississippi which one may consider remarkable.

The interviews speak for themselves but let’s analyze together what it can mean. For the whole semester we’ve been talking about education in black America. But now I can apply personal narrative to the facts. We can draw a few conclusions for each generation, in the 40’s and 50’s segregation had a detrimental effect on the experiences in their early life but the hatred of that condition breeds activism rather than sedentary. Then their children aspire to black excellence and see an HBCU as a place they can come into themselves and be around people like them and they pass onto their children. That in a short summary is my family’s experience in black education and education in the south before they participated in what became known as the great migration resulting in me being a Michigander. From the recent struggle of segregation and disenfranchisement to now generations of HBCU attendees and graduates. As we learned in class, the education of black people is done typically done in the black church and home first. A fact that was affirmed by Rose and Vera by their responses. As in the beginning, the family and the black church are pillars of ur education even for some of those who were not black but grew up as though they were like Mahalia. Now HBCUS can be added as a pillar at least for this group of black people. Through these shared experiences we develop a shared social consciousness/awareness and bond over both struggle and triumph. Education then is our greatest weapon that my family also possesses because as Grandma Rose and my mom observed it creates “unity”. When we have that we become unstoppable as innovators of trends and change, I’m honored my family contributed to that.