By Darreonna Davis

Howard University News Service and Inside Climate News

BALTIMORE—Lily Goldsmith was in her kitchen making soup when she picked up her phone and learned from Twitter that the tap water in her West Baltimore neighborhood was contaminated with E. coli, and residents were being advised not to drink it.

A West Baltimore native who always took pride in the quality of the city’s water, Goldsmith was dismayed to have to boil water and rely on cases of bottled water just to get by.

“Water is such an essential thing to just your everyday life, and you come to sort of take it for granted,” Goldsmith said. “It was really weird for that thing you normally take for granted to be sort of suddenly unsafe or maybe not unsafe.”

After the notice of water contamination in September, residents in the West Baltimore community banded together to support one another. Nonprofit organizations, like the St. Francis Neighborhood Center where Goldsmith works, responded to the crisis by distributing bottled water to those in need. Goldsmith said they distributed over 200 cases of bottled water and a number of water jugs for sustenance, disease prevention and peace of mind. The excess bottled water was used during their community harvest festival in October.

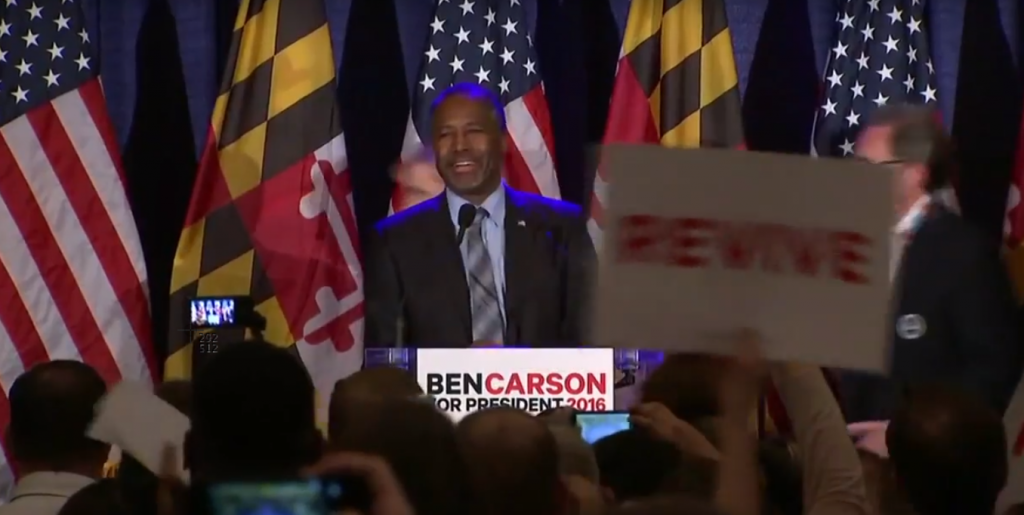

At Coppin State University, a historically Black college that sits within the neighborhood impacted by the boil water advisory, student leaders such as Ira Anderson Jr., an elementary education major and junior class vice president, worked to ensure students had access to bottled water during the advisory.

Ironically, just a week earlier, students held a bottled water drive to support their peers at Jackson State University after they and other residents of Jackson, Mississippi, were without water due to late summer flooding.

“We actually did a water drive for them and turned around the very next week and needed to do one for ourselves,” Anderson said.

The city of Baltimore issued a boil water advisory on Sept. 5 after detecting Escherichia coli — more commonly known as E. coli — contamination in the water. On Sept. 9, the city’s Department of Public Works released a statement officially lifting the boil water advisory after several negative water tests hinted at safe consumption.

An informational hearing occurred on Sept. 29 with the city administrator, the director of the Department of Public Works, the director of the Office of Emergency Management, the Baltimore city health commissioner, the Mayor’s senior director of communications and representatives from the Mayor’s Office of Neighborhood Safety and Engagement appearing before the city council to discuss the water contamination issue. Here, city officials attributed the water contamination to aging infrastructure.

E. coli seeps into tap water through sewage overflow, agricultural storm runoff and broken water pipes, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. Health impacts of E. coli include diarrhea and, in extreme cases, kidney failure.

“The uncertainty was very disturbing … especially since I got sick immediately after the boiled water advisory was lifted,” Goldsmith said.

Some people, like Goldsmith, have gone back to drinking tap water. Others, like Jerell Paul, a junior chemistry major at Coppin State, remain uncomfortable.

“You would never catch me drinking out the tap,” Paul said. “I try to keep my mouth closed when I’m in the shower. … I don’t really trust it.”

Paul expressed that he and his two roommates at Coppin fell ill following the boil water advisory. Goldsmith said that her fiance had a stomach illness at the start of the advisory, and that she fell ill with cold-like symptoms that were not Covid-related about two days after the advisory was lifted. Neither they nor Paul and his roommates have been able to trace their ailments directly to the contaminated water.

“On a psychological level, it felt kind of gross not being able to just drink water freely,” Goldsmith said. “Even if you have bottles of water available, it just feels really peculiar — it feels like you’re sort of ignoring some of those basic health needs, or sort of putting them on the backburner.”

“Also, even though bathing was sort of safe … it was sort of an underlying anxiety thing, sort of similar to how it was throughout the whole coronavirus pandemic. There’s that nagging anxiety in the back of your head about all the ‘what ifs.’”

Baltimore native and Coppin State University student leader Ira Anderson Jr., 24, committed to supporting his student body with bottled water amid the water contamination crisis. (Photo: Darreonna Davis/HUNewsService.com)

Baltimore native and Coppin State University student leader Ira Anderson Jr., 24, committed to supporting his student body with bottled water amid the water contamination crisis. (Photo: Darreonna Davis/HUNewsService.com)

Since that time, Coppin’s student organizations have been stashing cases of bottled water in the student activities center in case more contamination arises. An East Baltimore native living in West Baltimore, Anderson is just hoping to be as proactive as possible for the student body — something he criticizes local officials for not doing.

“I just feel like that stuff didn’t happen overnight,” Anderson said, arguing that rusted or corroded pipes should have been a “red flag” that triggered repairs. “Being proactive instead of reactive, like, let’s go ahead and handle it now,” he said.

Distributing bottled water is a task that many residents and organizations have taken on in response to contamination in communities across the country, most notably in Flint, Michigan, where lead and other toxins seeped into drinking water in 2016 caused by a change in water distribution systems two years earlier, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). In 2018, Blue Triton Brands Inc. began distributing its Ice Mountain brand of water at local help centers and provided at least 20 million bottles of water through the program’s conclusion in 2023. Volunteers around the country also donated water.

But water drives are a short-term solution to a long-term problem. The CDC reported that 51% of households said the physical health of at least one family member had worsened because of the Flint water crisis. And although the lead levels have been in compliance with federal standards for seven years, demand for bottled water remains as residents distrust the water system, according to local outlet MLive.

After the Mayor’s Office in Baltimore was criticized for the way it handled communications during the E. coli outbreak, Monica Lewis, the mayor’s senior director of communications, said that in the future all agencies involved will communicate with her office to determine the best response.

Following the outbreak, the city applied a 25% discount on residents’ water bills in October after the contamination issues of September. Anderson, whose water bill typically costs between $230 to $240, saw his bill reduced and was thankful to have some type of relief.

Although Paul has stopped using the water at Coppin State, his roommate, Jaime Tudor, a Prince George’s County native, is drinking the water again but staying prepared for the likelihood of another outbreak.

“I’m giving the water a chance,” he said. “I’m giving it the benefit of the doubt. I haven’t gotten sick or anything like that.” But should he get another boil water notification, Tudor added, “I’m back to what I was doing.”

Though it took her a while, Goldsmith has returned to her traditional usage of the water.

“I’ve definitely shifted back to just drinking water from the tap as I did before,” she said. “It definitely took me a little bit to get comfortable doing that again … but now I’m pretty much back to how I was before.”

Darreonna Davis is editor of HUNewsService.com and an environmental justice reporting fellow for Inside Climate News. This article is part of Howard’s Third Reparations project for the inaugural Solutions Journalism Student Media Challenge.