WASHINGTON, D.C. – Atop the U Street metro station sits an African-American Civil War Memorial, carrying the names of more than 200,000 African-Americans who fought for the Union in the Civil War. Each panel has a unit name, most of them regiments of US Colored Troops. A lesser known fact is that the accompanying museum sits across the street in an alley.

The museum is currently celebrating 20 years since its conception, although it formally opened its doors in January 1999. The idea for the museum came to former Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) member, Dr. Frank Smith, after meeting a descendant of an African-American soldier who had served in the Civil War.

“It was intriguing to me because although I had three and a half years of education at a good college in Atlanta called Morehouse, I had not read anything about these soldiers in the Civil War,” Smith said. He had just left Morehouse to complete a SNCC assignment in Mississippi, people to vote.

Years later, Smith had moved to D.C. and begun to serve on the City Council. He was tasked with the responsibility of revitalizing U Street after the 1968 riots following Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s death, which left the U Street corridor devastated.

Nancy Holden, of St. Cloud, Minn., was visiting a friend in D.C. when she stumbled upon the museum while looking at a map of the area. She had not learned about the troops in school or any time before visiting the museum. “I thought the number of actual troops was rather interesting. The heroic role they played is really rather phenomenal. It’s a shame that we haven’t focused on them as much,” she said.

The lack of education on these soldiers is what drove Marquett Awa Milton, the museum’s interpreter, to abruptly end his studies at the University of the District of Columbia and join the museum’s staff full-time.

“I like promoting the truth,” said Milton. “I’m doing this to investigate who are we, why we’re here. This will help me understand that our ancestors had the skills of building a powerful nation and their stories were not taught in the schools.”

Milton participates in what he calls “living history,” a series of reenactments in which teams go to the sites of the battles, dress up in replicas of the uniforms and fire black powder. He wears his war uniform to the museum every day, armed with a musket similar to those his ancestors would have used.

Like Milton, Smith says, many people come to the museum having done their own research. He estimates that of the 10,000 people that came to the grand opening, about 3,000 of them were descendants of African-American soldiers who had already done research and had the records to prove it. The mission of the museum then became to provide a formal place to archive these stories and act as a sort of information bank for researchers.

Twenty years later, the mission continues.

As part of its 20-year celebration, Smith participated in the inauguration of the George Washington Williams Walking Trail at Banneker Field in Washington D.C. to commemorate Williams’ wish to connect Howard University students with the knowledge of their history. The campus of Howard University is adjacent to Banneker Field.

Williams was a free black man who, at 14 years old, lied about his age to fight in the Civil War and fought under two different regiments. After the war, he tried to get a monument built to the soldiers in that space.

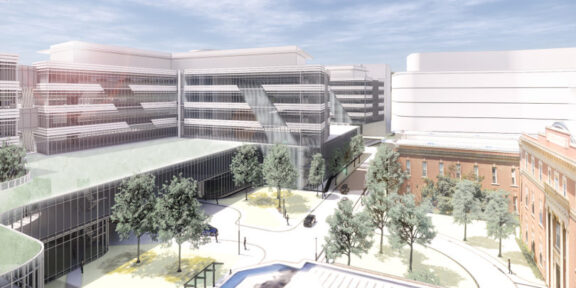

The museum also recently used a $3.4 million grant to purchase part of the Grimke School building, where it is currently housed, with plans to triple its exhibit size. Construction begins this spring. One of the exhibits is to be called “Bullets to Ballots: Voting Rights Legacy of the United States Colored Troops.” Another will focus on the heritage of former First Lady Michelle Obama, who has both maternal and paternal lineage tracing back to African-American Civil War troops.