While many Americans celebrate the arrival of warmer weather, D.C.’s immigrant population has the threat of deportation and detainment lording over them. The Central American Resource Center might be their only glimmer of hope.

Tucked away in the Salvadoran enclave of Columbia Heights Alex Rivas, who bartends at Rinconcito Salvadorian Tex-Mex, doesn’t shy away from discussing his personal experience as an immigrant in America.

“I came here in 2016 from Venezuela. I left because the socialism was just so bad,” says Rivas, who left the country due to its current political climate ruled by accelerated economic inflation, power cuts and lack of medicine and food.

Employed in a small immigrant neighborhood restaurant opened nearly 20 years ago, Rivas works shoulder to shoulder with immigrants from all over Latin America who live in fear of their lives being uprooted and being sent back to their countries of origin which they have fled in search of a better life.

“You know, people say ‘oh, well they should go back to their country, or go back to Mexico.’ Well, we also want people to understand that that’s not an option because Mexico faces X Y and Z. El Salvador faces X Y and Z,” says Sarah Hall Aguila, director of operations at the Central American Resource Center.

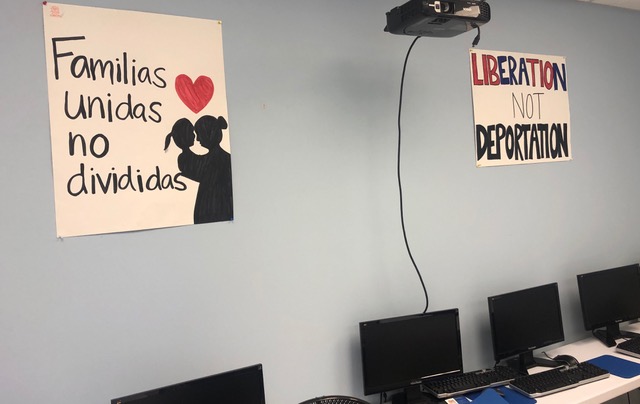

The Central American Resource Center (CARECEN) was established in 1981 to meet the needs of refugees fleeing violence and strife in countries like El Salvador, Nicaragua, Guatemala, and Honduras. All in which were experiencing civil wars during the 1980s and 1990s, environmental disasters and other life-threatening epidemics.

This organization has kept the goal in mind to protect the rights of Central American refugees seeking shelter in Washington, D.C., from the conflict in their home countries. The program provides direct services in immigration, housing, and citizenship. CARECEN also promotes empowerment, civil rights advocacy and civic training for Latinos.

“We provide immigration legal services first and foremost related to family-based immigration, we offer education classes to help prepare folks for the citizenship interview, and we do what we call transnational advocacy to understand the policies in place in the country of origin and what propels people to leave. So sometimes it’s easier to say what we don’t do,” says Sarah Hall Aguila.

“When TPS expires, many people’s entire lives will change for the worse if they have to go back to my country. Oh it’s going to be really really bad,” says Yasmin Romero-Latin, Mount Pleasant’s first Latina elected neighborhood commissioner. After coming to the U.S. in 1995, Romero-Latin is currently serving her fourth term on the Advisory Neighborhood Commission.

Romero-Latin says, “We’ve got a lot of problems in El Salvador, but I often mainly think of two things. Number one, the life for my country is really, really different than here. It’s like an entire 360-degree difference. It’s not only the fear of parents being deported in September, No. If the parents go, they’re taking their families there too. Second, a lot of kids who are brought here to grow up don’t speak Spanish. These children will never survive in my country if they don’t speak Spanish.”`

Recently, Trump administration’s decision to repeal Temporary Protected Status (TPS) in September of 2019 has been extended to January of 2020. The injunction will provide a reprieve to roughly 200,000 Salvadorans, 50,000 Haitians, 2,500 Nicaraguans and 1,000 Sudanese with the TPS designation.

After the expiration of TPS, are immigrants expected to go back to El Salvador? Aguila says, “It seems like that’s what the U.S. government thinks, but what our assessment shows is that most TPS holders are just kind of going to go back into the shadows. Yeah, that is what’s gonna happen.”

Aguila says, “Every year the class of people or the group of people renewing TPS ends up getting smaller because they’ve sort of self-selecting out, they’ve figured out other ways to gain more permanent legal status. Most of them have families probably already here, or they’ve married an American citizen. They’ve been here long enough that they’ve put down roots in this country. They have mortgages, like these people bought houses. So yeah, just leaving is not really an option.”

Nobody knows for sure what is going to happen January of 2020, but many agree that going home is not a viable option.

Like Alex Rivas whose residence status happens to be documented, more than three million Venezuelans have fled the country. These immigrants have been caught in a historical moment where their futures are uncertain, in a time where immigration has taken center stage in a tumultuous political landscape.

Following political discontent in Venezuela, Florida representatives Darren Soto and Mario Díaz-Balart, have introduced the Venezuela TPS Act of 2019, a legislative project that if enacted, will allow Venezuelans living in the U.S. who have fled the country’s repressive government and collapsing economy to qualify for TPS protections and work permits.

Would you ever go back to Venezuela? “No. I would never go back. Unless the Socialism got better, because I fear for my life.” says Alex Rivas.

“Most immigrants who come here aren’t trying to come steal jobs and take things. We have no other options. Most of us are fleeing the country and running for our lives. Every immigrant’s story is different, but most of us are running from danger.” says Rivas.

“People don’t understand how difficult this can be. Here, if my son has good grades, I buy him good shoes and a good phone. But not over there. I can’t give him anything when he gives me something good. If I give him something, the gangs will just steal it and rob him,” says Romero-Latin.

The question becomes, why would anyone continue to risk their lives making a journey to a place where they may never gain citizenship and risk being deported? To this Aguila responds, “The people in El Salvador will say, I would rather see my kid die trying to get to America than to just stay here and get killed on the corner.”