By Airielle Lowe

Howard University News Service

Patricia Ceasar received a reverse 911 call from the city of Winston-Salem, North Carolina, on a Monday evening that warned residents of an unspecified danger in close proximity and told them to evacuate.

“It was very nerve wracking,” said Ceasar, a Winston-Salem resident for over 30 years. “I have never in my whole life been evacuated and I was so shocked at the reverse 911 call that I called the police department to see if it was some kind of hoax … and they told me it was not a hoax and that I needed to leave.”

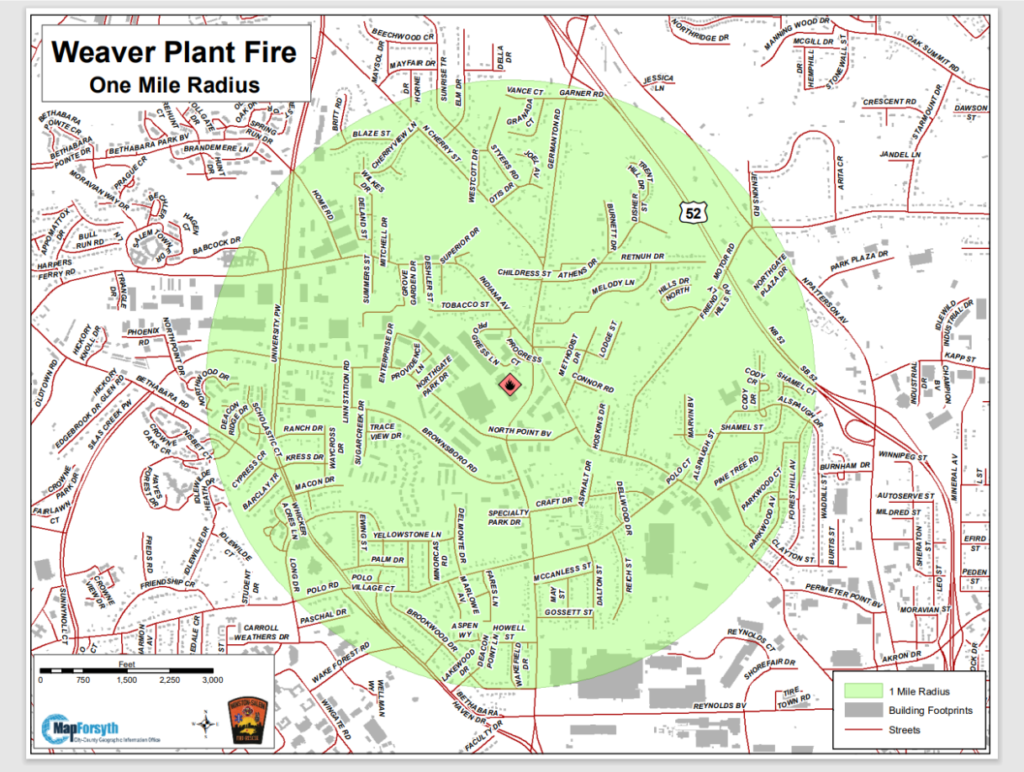

It turned out that nearly 600 tons of ammonium nitrate had caught fire at the Winston Weaver fertilizer plant on Jan. 31. The fire burned for four days straight, with firefighters being unable to approach and contain the fire, due to the risk of a deadly explosion with the potential to kill thousands. Instead, residents within a mile radius were told to evacuate, temporarily displacing a reported 6,000 people.

Ceasar, along with other nearby residents, fled in fear of their safety and once safe had that same fear for their homes and belongings they had left behind.

“If I had lost my home, I wouldn’t have had anything but the car I was driving,” Ceasar said. “How in the world would I start over?”

Ammonium nitrate, which can cause respiratory problems, is a chemical used to make fertilizers and explosives. The chemical can burn if in contact with combustible material and can also produce toxic oxides of nitrogen. In 2013, a fertilizer plant in the town of West, Texas, reportedly containing as much as 270 tons of ammonium nitrate, exploded after a fire broke out, killing 15 people and injuring 200 more.

Although the fire that ravaged the Winston-Salem plant has since been contained, with residents given permission to return to their homes, three lawsuits have been filed against the company for negligence, as well as the potential health concerns with the release of dangerous chemicals into the air and local waterways.

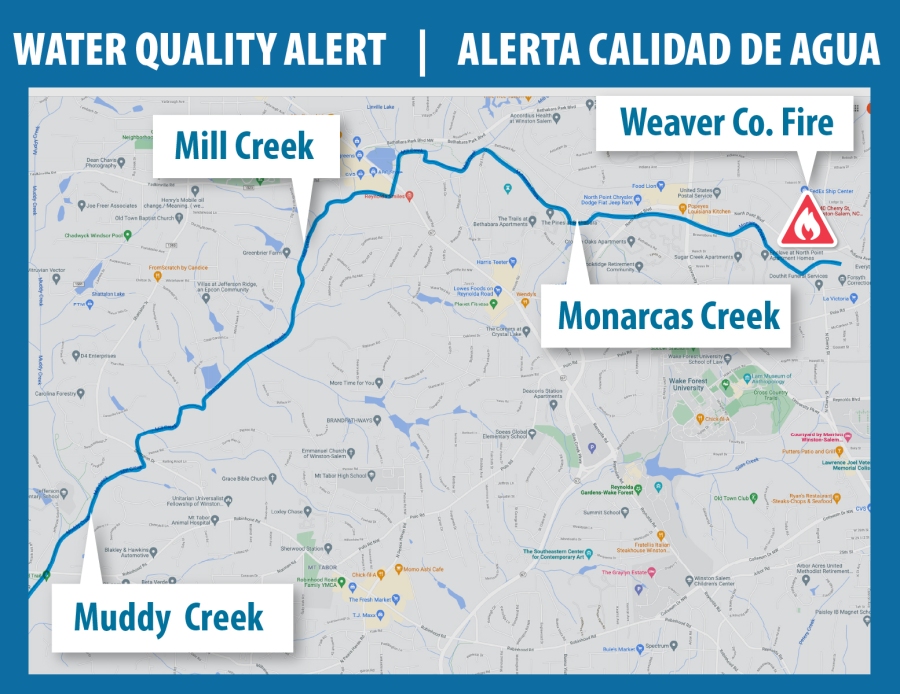

Soon after the fire ended, officials reportedly warned residents to stay away from local creeks due to chemical detection and released the following statement: “City officials are warning the public to stay out of Muddy, Mill and Monarcas creeks downstream from the Winston Weaver Co. fertilizer plant and to keep pets and other animals out of the creeks due to elevated levels of chemicals in the water resulting from the fire at the plant.”

Minor Barnette, director of Forsyth County Environmental Assistance and Protection, told Fox 8 that the air quality near the plant had improved greatly since the beginning of fire, but there has been little update on the status of local water supplies since the initial one.

Though the air quality has been deemed “breathable” and residents have returned home, the fire at the Winston Weaver has still left lasting, negative impacts on a community forced to pack up and leave at a moment’s notice, confused as to how they could live so close to a plant holding a significant amount of dangerous chemicals, without ever being notified.

Although Patricia Ceasar shared that she was familiar with the plant’s existence and drove past it often, she admitted that she, like others, were unaware of the plant’s contents. “All of us were wanting to know why was this amount of stuff up there, and nobody had any idea,” Ceasar said. “We were just clueless.”

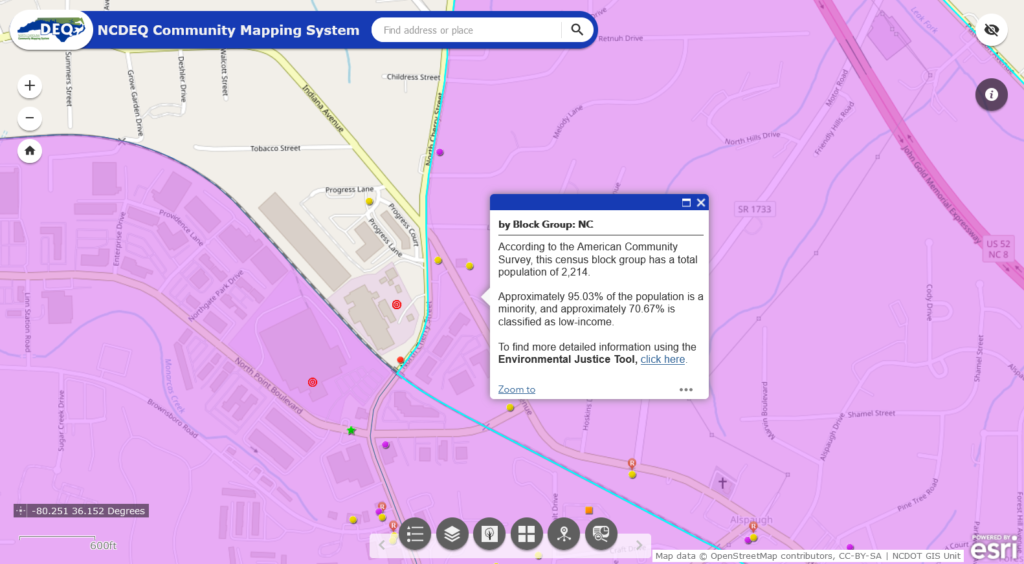

The chances of a fertilizer plant catching on fire and exploding are liable to happen anywhere in the nation and as such, affect any community who lives close by. However, African Americans are 75% more likely to live in “fence-line communities” (communities next to a company, service or industrial facility that have a direct effect on the community) and more likely (along with other people of color or POC) to be exposed to air pollution. As such, they are more likely to suffer from asthma, cancer and other chronic illnesses than other races.

According to the N.C. Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) mapping system, all areas bordering the plant are of a high minority and low-income population, with the area to the east consisting of 95% minorities.

And this is not a coincidence, but by design, as is the case with many communities of color disproportionately located near industrial areas.

Geographical Racism in Winston-Salem

In 1904, a water reservoir cracked, and 800,000 gallons of water poured into the street, killing nine people and destroying eight houses. The area of destruction, nicknamed “The Pond,” attracted African Americans after its rebuild as it was one of the few places they could find a place to live.

In June 1912, Winston-Salem’s Board of Aldermen enacted an ordinance that prevented Black people from owning or living on property in certain areas near white people.

The topography of The Pond created stagnant rainwater, which became home to industrial runoff from nearby factories. Through various practices enacted by city officials, Black people were unable to move out of their neighborhood or improve upon it, and The Pond became one of the worst neighborhoods within the city.

Although the 1912 ordinance was later ruled unauthorized and The Pond eventually underwent a “slum clearance project,” Winston-Salem continued to enact laws to divide the city by race and discourage white communities from allowing African Americans inside them.

This included the creation of a highway known as U.S. 52, which not only cut into the Black community located east of the highway, but also segregated Black residents from the white community on the west. The Weaver fertilizer plant sits about a mile west of the highway, and a majority of the residents around the plant are reportedly low-income people of color.

At the time of the plant’s creation in 1939, it was located outside of city limits. However, when houses began to be built in the area, African Americans were more likely to be able to afford the area near the plant than others neighborhoods, because of these geographical racist practices.

A Legacy of Environmental Racism

Winston-Salem is not the only North Carolina city guilty of geographical and environmental racism and injustice. In Eastern North Carolina where the majority of industrial animal farms reside, communities of color that have been disproportionately impacted complain of contaminated water from hog waste and rancid smells from decomposing animals and rotten eggs.

“There’s also a physical geography that often influences a lot of environmental injustice,” shared

Russell Smith, a geography professor at Winston-Salem State University and faculty lead for the Spatial Justice Studio at the Center for Design Innovation.

“For most of North Carolina, the western side of cities are a higher elevation and the eastern sides are lower,” Smith explained. “So, wastewater treatment plans are going to be in those lower lying areas.”

“The other physical geography piece that goes along with that is predominant wind patterns,” Smith added. “The wind tends to flow from the southwest to the northeast, and because of that polluting industries tend to be placed on the east side: one, so that they could collect sewer runoff and two, for smokestacks.”

A study from the North Carolina Medical Journal found that communities located near concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) have higher rates of “infant mortality, mortality due to anemia, kidney disease, tuberculosis, septicemia and higher hospital admissions/ED visits of LBW (low birthweight) infants.”

North Carolina is one of the top poultry producing states in the country, and poultry operations in the state that use dry waste systems are not required to have permits.

And to the northeast in Warren County, North Carolina, the state government decided that a poor, rural Black community would be the site for toxic waste dumping in 1982. Although residents protested for six weeks, the toxic waste was eventually deposited in a landfill in the community.

However, Ben Chavis, the leader of the movement who coined the term “environmental racism” after being arrested, sparked a national movement. Although the battle was lost in Warren County, across the nation Black Americans and other people of color are fighting against a history of environmental racism, first stipulated by geographical racism during an era of segregation and Jim Crow laws.

The first step is to recognize this legacy to prevent additional polluting industries in Black communities — as with the Winston Weaver plant.

Airielle Lowe is a reporter for HUNewsService.com. She also wrote about “forever chemicals” for this Breathing While Black Project.