Residents should report crime that abandoned properties attract, causing a decline in the value of neighborhood property.

A new family has moved into the house two doors away from yours. Suddenly, there is traffic in and out of the house daily. People congregate outside at all hours of the day and night. Profanity, arguments and loud conversations can be overheard. It appears drug sales might be taking place.

What can you and other residents do?

A lot, said an assistant attorney general of the District of Columbia and a community prosecutor with the Department of Justice.

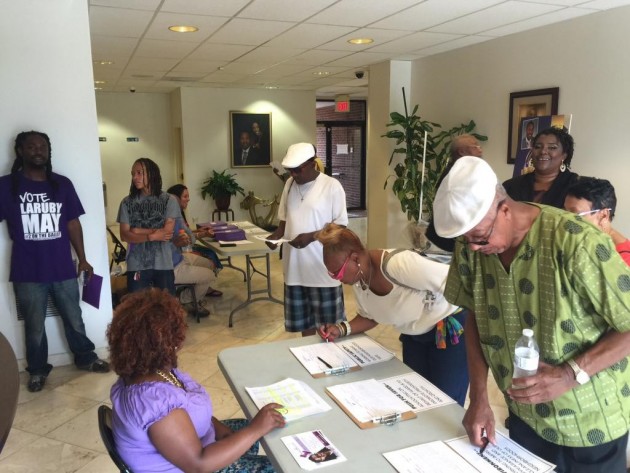

Asst. Attorney General Michael Aniton and Community Prosecutor Trena Carrington of the Department of Justice gave residents of the Petworth neighborhood a list of things they should do to protect themselves and their neighborhood during their recent Advisory Neighborhood Commission (ANC) meeting.

ANC Commissioner Donna Brockington noted that there were several complaints from residents about the noise in the neighborhood.

“Noise is definitely an issue,” Aniton said in response to Brockington’s concern.

But she also wanted to target some tougher community problems.

“I want to focus more on the drug, gun and prostitution aspect,” said Aniton, whose office handles housing code violations, businesses operating without proper licenses or permits, drug, firearm, prostitution and general nuisances.

“A nuisance property uses, sells, or reproduces drugs, keeps or stores firearms that aren’t registered or engages or practices prostitution in any manner.”

If residents notice property in the neighborhood that would be considered a nuisance property, he said, they should call the police. Once a complaint is made, the investigation would begin, he told the more than 50 residents in attendance.

Aniton stressed that although there may be suspicious activity going on in the community, the activity must be reported.

“Do [resident’s concerns] have to be an emergency [to call the police],” Brockington asked.

“No,” Aniton said. “A call can be anything.”

Police are first looking for evidence that the property has an adverse impact, Aniton and Carrington said.

That evidence can include increased fear of residents in the area, increased vehicular and pedestrian traffic, increased police calls, bothersome solicitations, dangerous weapons displayed, investigative purchases, arrests at or near property, executed search warrants and discharged firearms, they said.

One or more of those conditions has to be present for the property to be considered to have an adverse impact on the community.

But first, there has to be a call for service, followed by a search warrant and arrest reports on file as evidence against the property to begin a legal process against the property, Aniton said.

“Once we have the evidence that shows that there’s an adverse property, then we can move forward,” he said. “We can use that evidence to essentially bring a case against the property owner.”

Aniton and Carrington said after those conditions have been met, the following occurs.

Once there is enough evidence, a notice is sent to the property owner. The letter informs them that their property has been reported as a nuisance and asks what the owner plans to do to remedy the problem.

Remedies include putting up fences, installing lights outside of the property, initiating an eviction process or the destruction of sheds. The owner then has 14 days to respond to the notice.

If the owner agrees to cooperate and take the necessary steps to remedy the problem, the case is closed and considered successful. If the owner does not respond or responds stating that he or she is not going to remedy the problem, a complaint is filed.

The complaint turns into a criminal property case. The complaint asks the judge to order the owner to find and put in affect a solution the issue.

“An investigation can be from a month to a year or longer,” Aniton said.

“It’s a process,” Carrington added. “Sometimes it’s three or four agencies trying to combat the problem.”

Aniton and Carrington said residents with concerns could email them at Michael.aniton@gmail.com or trena.carrington@usdoj.gov.