By Chrisleen Herard

Howard University News Service

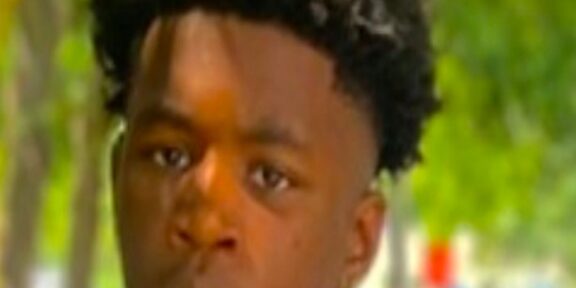

Tyre Nichols was a 29-year-old father and FedEx worker who loved skateboarding, taking pictures of the sunset and most of all his mother, whose name, tattooed on his arm, would be one of the last Nichols called out as he was being brutally beaten to death by five Memphis police officers on the night of Jan. 7.

“It’s funny, you know, he always said he was going to be famous one day,” Nichols’ mother, RowVaughn Wells, said last Friday in a news conference as his supporters continue to demonstrate around the country. “I didn’t know … this is what he meant.”

Candles in the shape of hearts lit Nichols’ memorial service on Monday at the Regency Community Skate Park in Sacramento, California, where his family and friends gathered to celebrate the life that he lived long before moving to Memphis to be with his mother during the pandemic.

Mourners then joined Wells at her son’s funeral on Wednesday, including Vice President Kamala Harris and survivors of others slain by police such as George Floyd and Breonna Taylor.

“He changed the world!” an individual is heard yelling from the church stands as a tearful Wells took to the podium to give thanks to all those who came to give tribute to her son while calling for Congress to pass the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act.

Nichols was on his way to his mother’s home when he was pulled over at the intersection of Raines and Ross Roads on suspicion of reckless driving, a speculation that has yet to be confirmed as the investigation continues into his death.

In spite of the original report claiming that an unarmed Nichols was irate, aggressive and violent, a police officer would be the one to open Nichols’ door, dragging him out of his vehicle and starting the actions that led to his death.

“You gonna get your a– blown the f— up! Get out the car. Get the f— out the f—in’ car!” an officer is heard yelling on police bodycam footage.

“Damn, I didn’t do anything!” Nichols attempted to explain. “Hey I didn’t, alright, alright, alright, alright. … You don’t do that, OK!”

In a relentless beating that mirrors the police brutality of Rodney King in 1991, Nichols was tased, pepper-sprayed, beaten, kicked in the face, hit with a baton and endured much more before dying three days later at a hospital. An independent autopsy would later reveal that he suffered from “extensive bleeding caused by a severe beating.”

With a taser gun pressed against his leg, officers pulled Nichols onto the ground. “Get on the ground! I’m gonna tase you; get on the ground! Lay down!”

Nichols attempted to shield himself from being pepper-sprayed and hit with several thousand volts of electricity. “Stop. OK stop. Alright, OK, alright!”

However, the yelling and threats didn’t stop even after he was put on the ground.

“B—-, put your hands behind your back before I break them … knock your a– the f— out!”

“Alright, OK! You guys are doing a lot right now. Stop! I’m just trying to go home.”

Former Memphis officers Tadarrius Bean, Demetrius Haley, Emmitt Martin III, Desmond Mills Jr. and Justin Smith were fired 10 days after the traffic stop occurred for excessive use of force, failure to intervene and failure to render aid.

“Aside from being your chief of police, I am a citizen of this community we share,” Memphis Police Chief Cerelyn Davis stated. “I am a mother. I am a caring human being who wants the best for all of us.”

“This is not just a professional failing; this is a failing of basic humanity toward another individual.”

Another six days later, on Jan. 26, a grand jury indicted the five officers on a second-degree murder charge for Nichols’ death, in addition to aggravated kidnapping and assault, official misconduct and official oppression. All but one, Demetrius Haley, are released on bond.

Two more officers have been relieved of their duty since Nichols’ murder: Former officer Preston Hemphill, for his participation and use of a taser at the initial police stop, and another former officer, who has not yet been identified. Hemphill, however, remains free without any current charges brought against him.

Finally, two emergency medical technicians, JaMicheal Sandridge and Robert Long, along with Lieutenant Michelle Whitaker, were also fired after “fail(ing) to conduct an adequate patient assessment” before an ambulance arrived on the scene, according to Chief Gina Sweat.

“This incident was heinous, reckless and inhumane,” Davis added.

The electrifying sounds of a taser are heard buzzing on police bodycam footage after a fearful Nichols managed to get away from the officers. Ultimately, the officers would later find him down the street at an intersection on nearby Castlegate Lane.

The second part of the footage is a 31-minute video that, although silenced, is nonetheless filled with Nichols’ screams as officers are seen holding him down and taking turns beating him until he laid lifeless against a police cruiser with no aid.

Nichols, handcuffed, waited for an ambulance to arrive on scene 28 minutes after the beating took place and he complained of shortness of breath.

“Tyre Nichols is calling out for his mom,” Ben Crump, the Nichols’ family attorney and renowned civil rights attorney for the families of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd, said at the conference. “He calls out three times for his mother. His last words on this earth (was), “Mom! Mom! Mom!”

“And when you think about his kidnapping charge, he said, ‘I just want to go home.’ I mean, it’s a traffic stop for God sake. A traffic stop. A simple traffic stop.”

“When Black people have simple encounters with police, they end up dead,” Crump continued. “We don’t hear about these things with our white brothers and sisters. We don’t see the videos of the police doing the most with white citizens.”

“And that’s where we gotta continue to speak to this police culture in America,” he said. “As much as those five officers killed Tyre Nichols, it was the police culture in America that killed Tyre Nichols.”

Police killings hit a record high in the United States in 2022 at 1,192 deaths, averaging almost 100 per month and surpassing the previous high at roughly 1,160 deaths in 2021, according to Mapping Police Violence. Black people accounted for 26% of those killed.

To help prevent a higher body count in the new year, peaceful protests have flooded cities like New York, Chicago and Memphis.

One protestor, who calls himself Loove Moore from Oakland, California, speaks about his experience from taking to the streets after Nichols’ murder.

“We wanna show everybody that we are here in unity. That’s what I got out of it,” Moore said. “It didn’t have to happen out here, but … the people are gonna stand up for the people. Just different groups of different groups and different tribes coming together to speak on it.”

Moore said he felt unity with young people, “kids on shoulders, different colors.”

Alan Chavoya, outreach chair of the Milwaukee Alliance Against Racist & Political Repression (MAARPR), who also protested this past weekend, said that a case such as Nichols’ bared a familiar face in the most populated city of Wisconsin.

“There were these popular cases that sort of came up amidst the George Floyd uprising a couple years ago,” Chavoya said. “We refer to this group as “Thee Three.” It was three young men of color, Antonio Gonzales, Jay Anderson and Alvin Cole Jr. and they were all murdered by the same police officer, Joseph Mensah, a Black police officer.”

“So here in Milwaukee, we understand too that … it doesn’t matter. A cop’s a cop, and it really doesn’t matter the race. …When they put that uniform on, when they have that badge on, we know what they’re capable of doing.”

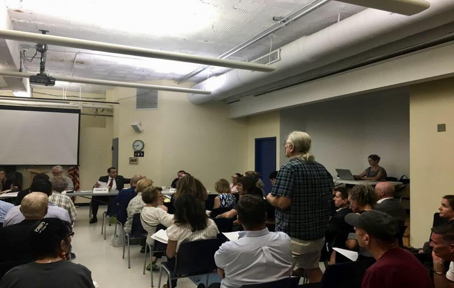

Chavoya then frames how he and MAARPR hope and plan to achieve police accountability and transparency in the future.

“Our big push is for community control of the police. So, what that means is that the people have the first and final say as to who polices them and how they’re policed, and this would take shape through a civilian police accountability council that’s democratically elected by different communities.”

“This board will have a direct say over the police budget, direct access to investigations internally into the police. … They would also be able to hire and fire police officers, and so that’s the big dream of community control that can then lead, you know, to more, effective change.”

A failed attempt at protecting the community, The Streets Crimes Operations to Restore Peace in Our Neighborhoods, otherwise known as the SCORPION Unit that was launched in 2021, was disbanded after the five original officers instead brought violence to the neighborhood that they were responsible for guarding, just yards away from the Wells’ family home.

“I was telling someone that I had this really bad pain in my stomach earlier, not knowing what had happened,” Wells said, “But once I found out what happened, that was my son’s pain that I was feeling, and I didn’t even know.”

“But for me to find out that my son was calling my name, and I was only feets away and did not even hear him, you have no clue how I feel right now. No clue.”

Nichols was on his way home to have dinner with his mother when officers pulled him over, after taking pictures of the sunset at Shelby Farms Park for what would be his last time.

Chrisleen Herard covers crime and legal issues for HUNewsService.com.