By Keely Aouga, Lindsey Desir and Joshua Heron

Howard University News Service

Carter Sessoms feared that if affirmative action was deemed illegal, the presence of minorities might decrease at campuses across the country.

“Affirmative action was to put in place some equitable strides within the workforce and education systems because of the socioeconomic disparities perpetuated by racial bias that existed in these institutions,” said Sessoms, a history major on a pre-law track at Howard University.

“As someone who’s going to law school after my undergraduate time at Howard, it is concerning,” she added. “During the application process will the circumstances that were directly related to racial disparities that affected me overall as an applicant be considered? This is what I’m left with: If someone’s hand isn’t legally pushed to consider applicants of equal talent, exam stats, and academic potential, will they? Will they consider me?”

The merits of affirmative action as a remedy to enhance diversity has long been a subject of debate. But how has it worked and who has benefitted? What are the implications of affirmative action, and are there options?

The merits of affirmative action as a remedy to enhance diversity has long been a subject of debate. But how has it worked and who has benefitted? What are the implications of affirmative action, and are there options?

The debate was heightened in October when the U.S. Supreme Court heard oral arguments in Students for Fair Admissions v. University of North Carolina and Students for Fair Admissions v. President and Fellows of Harvard College. In 2014, conservative activist Edward Blum sued Harvard University and the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill over their use of race-conscious admissions.

Title VI of the Civil Rights Act bans race-based admissions that, if done by a public university, would violate the Equal Protection Clause under Gratz v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 244, 276 n.23 (2003). Now that the Supreme Court has deemed race-based affirmative action unlawful in a 6-3 vote on Thursday, the scope of college admissions and the rates of diversity among college campuses across the country could be forever changed.

The History of Affirmative Action

Affirmative action is defined as, “a set of procedures designed to eliminate unlawful discrimination among applicants, remedy the results of such prior discrimination, and prevent such discrimination in the future,” according to Cornell Law School’s Legal Information Institute. It can be applied to both higher education and employment.

The term was coined during John F. Kennedy’s presidency. It has been controversial since then and the reason for many court cases. Under President Kennedy’s Executive Order 10925, affirmative action’s purpose was to “ensure that applicants are employed and that employees are treated during employment without regard to their race, creed, color or national origin.”

When many people mention affirmative action, they are referring to the removal of discriminatory practices in employment and admission to higher education that take into account the history of oppression that marginalized groups have faced in this country and their inability to have the same opportunities as white people.

Opponents believe that affirmative action does the opposite of its intentions: ending discrimination. Connecticut College has created a web page dedicated to explaining support and opposition.

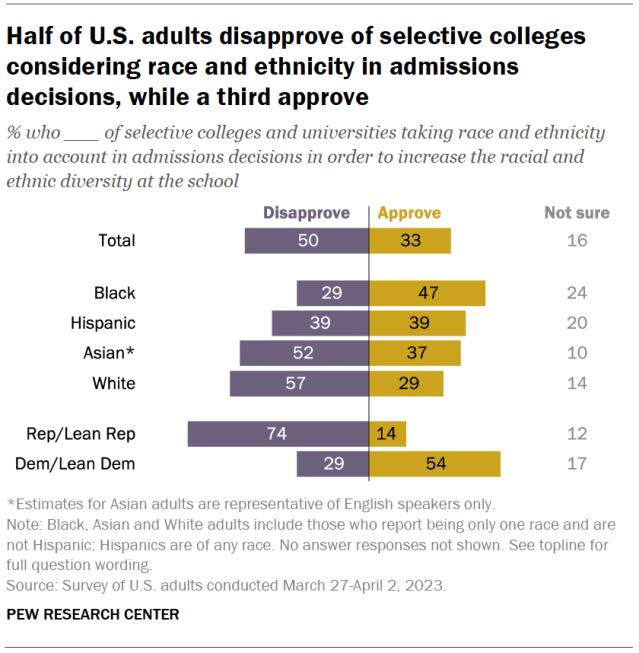

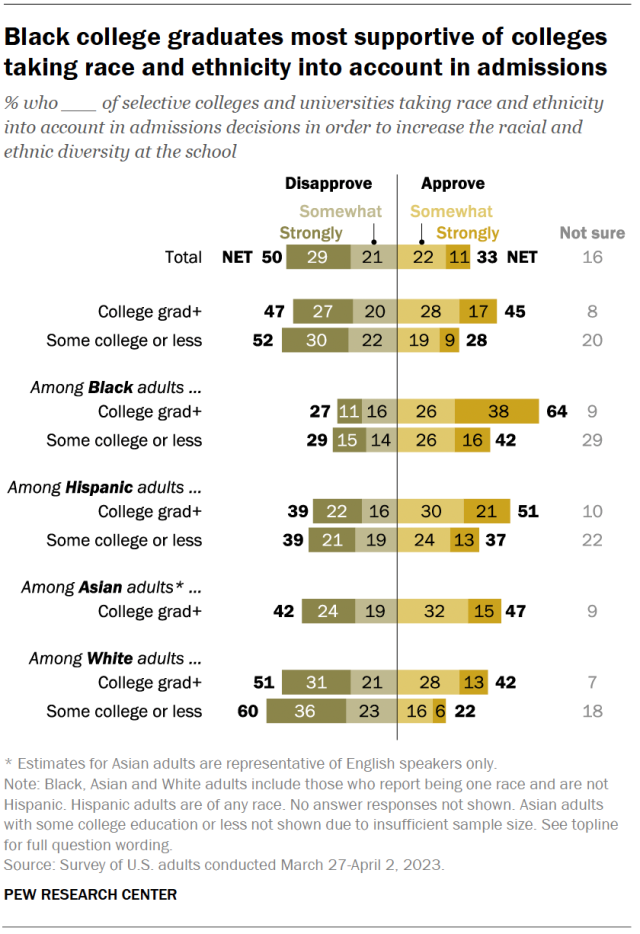

More than half of Republicans (74%), white citizens (57%) and English-speaking Asian Americans (52%) disapprove of using race and ethnicity in admission decisions, according to a recent survey from the Pew Research Center. A third of African Americans (29%) who were surveyed also disagree.

“I don’t think there’s a solution to the race problem,” said Craig Ricard, a 2007 Howard law school graduate and a public defender in the District of Columbia.

“Affirmative action is in place as a solution,” the 16-year veteran said before the Supreme Court decision. “It’s a handout to Black people and something used to soothe the open wound of oppression. I don’t believe the oppressed people can go to the oppressor to discuss a solution.”

Ricard likens affirmative action to a “drink of wate

“It’s a drink of water that calms the oppressed down so it’s easier for the oppressor to keep their foot on their neck, because there will be less complaining.”

Nevertheless, Ricard admits affirmative action has done some good, but doesn’t see it as a sustaining force in the race to equality.

“I’m happy about what it has done, but I don’t think it’s a long-term solution to the issue,” Ricard said.

Additionally, some opponents believe that affirmative action grants opportunities to those whom they believe are unequipped to perform well in higher education or the workplace, thus stripping away opportunities from those who are “better deserving” and often white. However, studies show that those who are admitted to schools or hired for jobs through affirmative action meet and often succeed the same qualifications as their white counterparts.

Since the implementation of affirmative action, a number of cases have been brought before the court to determine whether it is a legal system. These cases include Grutter v. Bollinger, Regents of the University of California v. Bakke and Fisher v. University of Texas.

DeFunis v. Odegaard in 1971 was the first case questioning affirmative action’s legality. Marco DeFunis, a white man, argued that he was denied admission to the University of Washington law school because affirmative action was used to admit “unqualified” minority students above him, according to The University of Washington’s “Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project.”

The case that followed DeFunis v. Odegaard is Regents of the University of California v. Bakke where the court allowed “the use of race as a factor in admission if it was part of an overall evaluation of an applicant,” according to PBS’s Newshour

The most recent case against affirmative action prior to the hearing in late October was Fisher v. University of Texas involving a white woman named Abigail Fisher.

The use of affirmative action at the University of Texas was upheld, and Fisher is now a leader of Students for Fair Admissions, which brought the cases against UNC and Harvard.

Students for Fair Admissions is a “nonprofit membership group of more than 20,000 students, parents and others who believe that racial classifications and preferences in college admissions are unfair, unnecessary and unconstitutional,” according to its website

Like DeFunis, Bakke and Fisher, Students for Fair Admissions believes race and ethnicity shouldn’t be used as factors in college admission, contending that it gives unfair advantages to marginalized groups.

In the recent Pew study, 28% of African Americans said other people assume that they have benefited unfairly from affirmative action. In reality, affirmative action does not benefit people of color as much as some claim it does.

Affirmative Action: Who Are Its Beneficiaries?

When Fisher first brought her case to court, her main argument was that she was denied admission to the University of Texas because she is white. Most controversy surrounding affirmative action falls on the debate of whether it is fair for racial minorities to benefit from such a system.

Cases similar to Fisher v. University of Texas, such as Grutter v. Bollinger, Gratz v. Bollinger and Hopwood v. Texas, argue that the practice is unfair. Supporters of this cases believe that affirmative action works against white people and instead offers opportunities to those who are less deserving based solely on the color of their skin.

It is true that racial minorities receive many benefits from affirmative action. Between 1976 and 2008, Black and American Indian/Alaska Native people saw their share of total college enrollment increase by 39 percent and 46 percent, respectively.

However, schools that banned affirmative action have seen a drop in admission of students from racial and ethnic groups. When California banned it in the late 1990s, the percentage of Black undergraduates at the University of California, Berkeley fell sharply –- from 6% in 1980 to only 3% in 2017.

But while affirmative action has helped to diversify schools and workplaces, white women are proven to be the primary beneficiaries.

Affirmative action isn’t based on race alone. Gender is an important factor, which in turn helps white female applicants just as much or even more than diverse applicants. According to one study, 6 million women, mostly white, have utilized affirmative action to their advantage.

The same study also states that “according to state data, white women hold 35% of top administrative jobs in Washington, compared to 5.8% for women of color; furthermore, white women receive about 5% of state government contracts, which, although it is a paltry percentage of the total, is still larger than the 4% received by all people of color combined.”

Implications and Options

The Supreme Court ruling on the use race or ethnicity as a factor in admissions will affect student bodies across campuses in America. The admission process could become an impasse to the American dream instead of providing the opportunity to achieve it. Diversity could decrease dramatically on campuses and in the workplace as a result.

So much for post-racial America, affirmative action proponents say.

“It is a complete misnomer to suggest this is about ‘colorblind,’” Vice President Kamala Harris said during an appearance in Louisiana, “when, in fact, it is about being blind to history, being blind to data, being blind to empirical evidence about disparities, being blind to the strength that diversity brings to classrooms, to boardrooms.”

A coalition of 25 legal, civil rights and community groups primarily filed an amicus brief in opposition to the two October cases citing the “devastating effects that forced blindness has had on California’s people, institutions, and economy.”

“For example, in the three years after Proposition 209, the average enrollment rate of Black and Latinx students declined by 21.3% and 12.7%, respectively, at the University of California (UC) campuses,” the coalition said.

Another amicus brief reported similar results in Michigan after approval of Proposal 2, a 2006 amendment to the state’s constitution.

The brief notes that the University of Michigan experienced “a marked and sustained drop especially among the most-underrepresented groups, Black and Native American students, whose enrollment has fallen by 44% and 90%, respectively, since Proposal 2 was adopted.”

It added that the lack of diversity contributes to isolation and affects student’s well-being: “Fully one quarter of underrepresented minority students surveyed indicated they felt they did not ‘belong’ at U-M, a 66% increase over the last decade.”

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, one of the three Supreme Court members who voted in favor of affirmative action, said in her dissent: “If the colleges of this country are required to ignore a thing that matters, it will not just go away. It will take longer for racism to leave us. And, ultimately, ignoring race just makes it matter more.”

In writing for the majority, Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. appeared to urge schools to proceed carefully in shifting course, a warning that is likely to spill over to corporations.

“As all parties agree, nothing in this opinion should be construed as prohibiting universities from considering an applicant’s discussion of how race affected his or her life, be it through discrimination, inspiration, or otherwise,” Roberts wrote. However, he added that “universities may not simply establish through application essays or other means the regime we hold unlawful today.”

“What cannot be done directly cannot be done indirectly,” Roberts said. “The Constitution deals with substance, not shadows.”

Questions linger: Will there be alternatives to affirmative action? How can diversity be enhanced on campuses?

When California banned race as a factor in admissions for public education under Proposition 209 in 1996, only 96 African American students were in the first-year class of 5,000 at UCLA a decade later.

However, the school began considering family income, first-generation status and GPA. In addition, more was invested in outreach and recruitment throughout the University of California system. Consequently, the percentage of Black students at UCLA, which also has the highest number of applicants in the state system, has increased, but not to pre-Proposition 209 levels, according to a UC system 2018 report on representation and other data. Except for UC Berkeley and UC Riverside, other UC schools also saw increases.

At UC Davis, the School of Medicine has been using adversity scores through a socioeconomic disadvantage scale known as SED, which includes family income and education, in addition to other standard criteria such as grades and test results. The SED scale is intended to increase the diversity of doctors and help to address health disparities.

“Black and Hispanic medical students are three times as likely as their White counterparts to come from families with combined parental incomes of less than $50,000,” faculty members said in an article that they co-authored for the Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved at Meharry Medical College. They “are more likely to provide care for patients of color and to practice in high-need areas with fewer health services.”

In criticizing the Supreme Court’s decision, President Joe Biden advocated adversity criteria such as the SED scale. The Biden-Harris administration is also directing the U.S. Department of Education to advise colleges and universities on how they can legally address diversity. The education department also plans to hold a national summit.

“Our colleges are stronger when they are racially diverse,” Biden said in a briefing after the ruling. “We cannot let this decision be the last word.”

Below are four ways to increase diversity:

Economics and Education

Low-income students disproportionately come from under-represented groups. Schools that prioritize them could enhance their diversity.

In addition, colleges and universities could cut back on legacy admissions for the children of alumni – a preference reported by 787 institutions, according to James Murphy, a senior policy analyst for Education Reform Now in a fall 2022 report, “The Future of Fair Admissions, Issue Brief 2: Legacy Preferences.”

“Many highly ranked universities and colleges enroll more legacies than Black students,” Murphy said.

Jackinia Andre is an example of a student with financial difficulties stemming from a health scare in her family.

“In my junior and senior year of high school, I worked a great amount of hours in fast food restaurants and retail stores because my mom became sick and wasn’t able to work as much,” Andre said. “At one point in my senior year, it was only my mom and I, and I worked up to 30 hours a week. I did this to save money for college and to buy groceries to make the burden lighter for my mom.”

As a result, Andre was not fully able to invest herself in school and the community as much as she would have liked.

“I didn’t get the chance to participate in extracurriculars, do community service or have the same grades as my peers,” Andre said. “Luckily, my dean and teachers advocated for me. If the colleges I applied to didn’t use affirmative action in making their decision to accept me, I would’ve been in great trouble.”

She ended up selecting Howard University, where she is a political science major on a pre-law track.

Ring the Pell Bell

A substantial number of Black students receive Pell grants, according to the National Association of Student Financial Aid Administrators (NASFAA).

“Students of color are more likely to be Pell Grant recipients, with nearly 60% of Black students and roughly half of American Indian/Alaska Native and Hispanic students receiving a grant each year, compared with just under one-third of white students,” NASFAA reported in a 2022 issue brief on the Pell Grant.

“Additionally, roughly half of first-generation college students and student parents, and almost 40% of student veterans, are Pell Grant recipients.”

Another option is to offer free tuition, such as some states and the District of Columbia. In addition, out-of-state public institutions can decide whether to give special scholarships to Pell Grant recipients.

Diversity Has Become a Sport, So Recruit Minors

To maintain diversity, more admission representatives must divert from campus and go to local or regional high schools.

Affirmative action might be deemed unconstitutional, but action is a right every American can make. Going to high schools and recruiting first-generation students will help to keep diversity leveled. Hispanics and Blacks consist of the highest percentage of first-generation students.

It Is Time for the SAT to SIT?

The SAT was created with a purpose – as a determining factor for admission to a higher education institution. However, Black and Hispanics underperform most in the math section.

The underlying source of the gap in SAT scores is the wealth gap. Many Black and Hispanic students cannot afford tutoring and after-school programs to prepare for the SAT. Some schools they attend aren’t fortunate enough to provide essential resources either. Therefore, they are left without guidance to take a test to determine their future.

Sessoms questions whether sustainable solutions are possible given the state of the Supreme Court.

“It is hard to believe there will be an entity to replace affirmative action to still allow minorities a fair shot at their educational and workplace opportunities, because we may have the same SCOTUS for a prolonged period of time,” Sessoms said. “Therefore, the ruling of any similar case would be more than likely the same with this potential precedent.”

Sessoms believes that while their implementations are improbable, alternatives to affirmative action ending are present.

“Because socioeconomic disparities are so closely connected with racial disparities, there could be a work by these institutions to admit the highest-achieving students from specific communities and regions whether it’s by county or ZIP Code, etc.,” Sessoms said. “And this way there’s still a higher potential for racial diversity, and also reflected in diversity of background, sex, beliefs, etc.”

A common thread being sewn into each option is that maintaining diversity does not start at the secondary education level. Maintenance of diversity begins at the nativity of the one disproportionately affected.

The Supreme Court can end affirmative action, but the solutions must be poured into the centrifuge tubes labeled wealth, education and social gap to maintain diversity and give under-represented students a chance at receiving the that they desire and believe they deserve.

Keely Aouga, Lindsey Desir and Joshua Heron wrote this article as reporters for HUNewsService.com. The article is part of Howard’s Third Reparations project for the inaugural Solutions Journalism Student Media Challenge.