Editor’s Note: This story originally appeared on The Black Capitale, a Newslab Capstone Project.

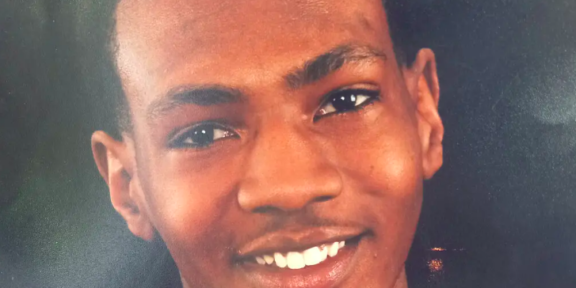

WASHINGTON– Lawrence Carpenter was sent to prison on drug-related charges in 1991.

Carpenter who was born in one of the most dangerous neighborhoods in North Carolina began selling drugs, at a young age, as a way for him to survive. His father was in and out of jail and his mother was addicted to drugs. He didn’t have any guidance besides the streets.

After selling drugs for a number of years, Carpenter’s luck ran out when he was arrested in Philadelphia after a lengthy chase and thrown in a cell at five in the morning. He was only 17. Despite running drugs with his crew, he was the only one caught. Leading up to his trial, he was offered less time if he gave up his drug mates, but Carpenter refused and was given a six-year sentence.

“I remember my lawyer came to me three times with a 40-year plea bargain,” Carpenter to The Black Capitale.

“The last time he came to me with that bargain, I called my mom crying telling her I couldn’t do 40 years. At that moment she said the realest thing ‘You in there playing around thinking it’s a game well it’s your life they playing around with. Better sit down and learn your laws and learn what they are doing to you’.”

But when he was released on parole, Carpenter went straight back to the drug game.

“I’m what you young folks call the plug. I was the biggest drug dealer in my city,” he lightheartedly joked.

While Carpenter listened to his mother and got familiar with the law, it didn’t help him from returning to jail five years after he was released.

He believes he avoided being caught for so long because of his first sentence; he had taught himself the law and knew how to break it. It wasn’t until 2002 that Carpenter had to turn himself in for a parole violation. By this time he was 28, recently married and had the responsibility of taking care of a baby girl.

“I only spent 11 months the second time I was incarcerated and it was way worse than the six years,” he said. “This time I’m grown and I’m feeling stupid because I thought I was so smooth I wouldn’t get caught. I wasn’t afraid because I was a living legend in there, but I had a family so I was more focused. My mentality was I have a little bit saved so for those 11 months, I was reading about starting a business. I knew when I got out I wasn’t coming back to prison.”

So started a business he did.

A new start

Carpenter started his own janitorial business with only $400. He chose this route because he didn’t want to go back to school for too long or start anything that depended on to many people. And most importantly, because for many released from prison, finding a job can be an insurmountable exercise.

Being labeled an ex-felon in America, strips these people of basic civil rights. Ex-cons aren’t allowed to vote, aren’t allowed to travel abroad, aren’t allowed to join the military and aren’t allowed financial aid for education. For many, reintegrating back into society is extremely difficult.

In the US, the mass incarceration rateis 707 adults per every 100,000 residents which is the highest in the world—by a huge margin. According to the 2010 Census, there were 2.3 million prisoners in the US. Black men only are only 6.5 percent of the population, but make up 40.2 percent of the prison population. A study by the Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR) found that 15 to 30 percent of previously incarcerated people are less likely to find jobs upon release.

Carpenter taught himself the ins and outs of running a business. His company, Super Clean Professional Janitorial Service, based in North Carolina, now employs 73 people and has 28 subcontractors. It also provides commercial cleaning services in three states and has been recognized for its service by the City of Durham.

“I never attempted to work for anyone else. I knew I was in a situation that I was going to be prejudged in and I didn’t want to live in poverty. I always had an entrepreneurial spirit I was just in the wrong game at first,” he told The Black Capitale.

Inmates to Entrepreneurs

For some former inmates, starting their own businesses is the only way to survive after prison. Inmates to Entrepreneurs, a non-profit organization based in North Carolina, offers currently and formerly incarcerated people the tools to “start their own business and engage in entrepreneurship by providing resources, mentorship, and hope.”

“We offer two courses: a two-hour course and an eight-week course,” said Jaclyn Parker, Inmates to Entrepreneur’s director. “The two-hour course is for those who are currently incarcerated and the eight-week course is for those who are released. In both courses we help them brainstorm ideas, give them business books, and articles pertaining to the related field,” she continued.

The vision of the program is to reduce the rate of recidivism. Recidivism is defined as the tendency for a convicted criminal to re-offend. In 2016, The United States Sentencing Commission found that nearly half (49.3 percent) of offenders released from prison in 2005 were rearrested within eight years for either a new crime or for some other violation of the technical conditions of their probation or release.

“People’s first instinct is to survive. So when people get out they have the tendency to go back to what they know,” said AJ Ware, executive director of Inmates to Entrepreneurs.

“Most people think that because someone is incarcerated that they are dumb and some of the most intelligent people I have come across were formerly incarcerated. Even your local drug dealer, that’s a business it’s an illegal business but it’s a business. They have customers and they have to sell that product for profit and reinvest it to buy some more. That’s business 101.”

Ware served a four-year sentence for committing a robbery at age 25. Upon release, he started his first business with $25. Ware and his colleagues encourage their students to start low-capital businesses.

“(Start) something service based, so that they can walk out the door and start working and making money.”

The eight-week course is provided three times throughout the calendar year. Even though a several will show interest, only about six to eight graduate from the program.

“The biggest challenge for a lot of our students is transportation,” said Parker. “For this past class, we had about 30 people sign up, 20 showed up for the first class and only 13 graduated. Out of that 13, five were women. Also, sometimes people’s parole changes so they can’t travel the distance they need to for the program. Fortunately, we haven’t had anyone be rearrested since I’ve been here.”

Carpenter became a mentor for the Inmates to Entrepreneurs program after seeing Brian Hamilton, founder of the program, on the news. Carpenter had been doing` community work in the area and wanted to get more involved and was intrigued by the program Hamilton presented. From their meeting, Carpenter respected Hamilton’s honesty and knew they could work together.

Although Ware and Carpenter have successful businesses now, it wasn’t an easy road to get there. For Carpenter, his biggest fear when starting his business was being able to present it professionally. He firmly believes that whatever you practice is what you become.

“One of my greatest fear was that I had practiced being ignorant for so long that I became ignorant,” Carpenter said. “My vocabulary was like ‘what’s up homeboy’ ‘how you doing playboy’ so when it came time to be professional and present my company I didn’t have the confidence to speak to people.”

Because of that lack of confidence, Carpenter chose to surround himself with more business -like minded people. Now as the mentor to younger inmates, Carpenter teaches his students to find what motivates them. He states there have been times where he was lazy and didn’t want to work but his motivation was to provide for his family. He didn’t want them to grow up in poverty like he did.

Being labeled an ex-felon comes with common misconceptions such as once a criminal always a criminal, they can’t be trusted and they are lazy. According to the Bureau of Justice, only 12.5 percent of employers said they would accept an application from an ex-convict.

Carpenter’s life isn’t consumed only by his business he also uses his proceeds from his business to give back to the community.

“I donate a lot of money to my old neighborhood,” Carpenter said. “Specifically, there were two guys one just signed to play football at Oregon and the other plays at Morgan State football. I remember seeing them when they were younger and I was like ‘oh Lord they not about make it.”

He continued, “The one who signed to Oregon his dad used to run with me in the streets and was doing time and then his mom got arrested by the feds so he started living with my cousin and I took care of them. I believed in them and I saw them try. I just wanted to see them win.”

Carpenter and Ware were able to change their lives around even with laws preventing them from succeeding.

“I just want to see people win,” Carpenter optimistically said. “I want to see reform. I want to see changes in our judicial system. I’m not saying that prison is skipped over white people but if you catch a white person he got really caught up in something.”