By Joy Young

When Isabella Miller and other members of Howard University’s Youth Justice Advocacy program walk into the D.C. Youth Services Center, the group is immediately subdued by the severe atmosphere of their surroundings.

Armed guards instruct students to take off their shoes, pass them through metal detectors, and pat them down to check for weapons. Then, guards usher them through the center to the living quarters, where students, not so different from themselves, wait in anticipation.

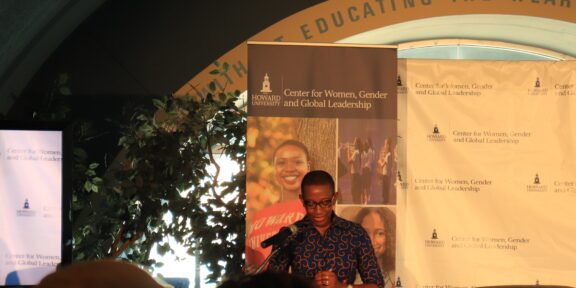

The Youth Justice Advocacy Program (YJA) is a Howard University organization created to advocate for reformed youth justice policies. They also mentor young people who have fallen victim to the school-to-prison pipeline, a term that describes how marginalized students are more likely to enter the criminal justice system due to a lack of resources and preventative policies.

The chapel-based group, which partners with the D.C. Youth Services Center, serves as a holding facility for 12 —to 21-year-old students who await sentencing.

The eight-week program, called “Build Better Dreams,” centers on a reflection-based discussion about personal goals and interactive activities, with game days and trust-building practices every other week to bond with students. The program engages in a variety of activities, from writing letters to the students to playing spades with their mentees.

Miller serves as the communications manager for the youth program and said the guilt of leaving the facility is more complicated than the strict check-in process.

“I feel that I am leaving behind students that we all care about deeply—we can go back to our normal lives after we’re done mentoring, our mentees cannot,” Miller said, “Some students have

shared how scary it is to sleep at the facility at night, and there are a lot of things they don’t have access to, like bedsheets and socks, in some cases.”

According to Miller, the students are sent to the facility for a wide variety of crimes. After their time is up, they will either leave to go home to a group home, wait on trials or be relocated to a different facility.

Hassana Arbubakrr, the President of the Youth Justice Advocacy program, emphasizes that most of the program’s children are victims of circumstance.

“These are middle and high school students that go from going to school every day, getting their lunch boxes together, to being behind bars and away from their families in a matter of seconds,” she said. “Possibly because they were in the wrong place at the wrong time.”

However, Arbubakrr believes that there is still hope that they will get out and wants the program to help them build a stable framework if they do.

“We try to create restorative practices while they’re in there so they’ll make better decisions, have a sense of direction, and avoid ending up in the same predicament,” Arbubakrr said.

Black students are three times as likely to be suspended or expelled than white students. They are also three times more likely to be in contact with the juvenile justice system after that, according to the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU).

Youth Justice Advocacy Members partnered with HU Chess Club to teach DC Youth Center students Chess in 2023. (Photo Courtesy of @hujusticeadvocates on Instagram)

“The students have had to grow up very quickly, being so young,” said Miller said. “A lot of them have dealt with financial instability for as long as they can remember and feel like committing a crime is the only way they can get out of it.”

“Some of these kids commit crimes just so they can have a place to lay their head at night,” she adds. “I remember we once asked them where they see themselves in ten years, and every single one of them said they see themselves still in jail—that had a big impact on me.”

Studies have shown that youth who are arrested without appropriate support or rehabilitation experience high rates of arrest and re-incarceration, according to the Sentencing Project.

“When these kids get out, the adults around them aren’t always able to help them, and they feel like they have to turn to crime to survive. It’s a hard situation to get out of,” Miller said.

Though the youth program is chapel-based, anyone is welcome to join. The chapel introduced the organization to Howard under the name Ministry for Youth in 2011, and it has grown in size from there. The group grew from about 60 to 100 this year, facing a huge uptick in their applications, and hopes that the interest in their work will continue to grow.

Wesley Ramsey IV, a junior finance major at Howard, worked with the youth program for the first time this semester. He says that he enjoys establishing connections with the kids while doing activities that they like to engage in.

“It’s cool building connections with the younger youth… I like that it’s not always like sitting down, but in ways that they can express their happiness and joy,” he said.

Ramsey shared that his favorite memory is mentoring kids during their gym time.

“We have to build rapport with the students in order to serve them,” Arbubakrr said. “We don’t want them to feel like we’re bossing them around, we want them to trust us and feel like we’re supporting them.”