By Jaylen Williams

Howard University News Service

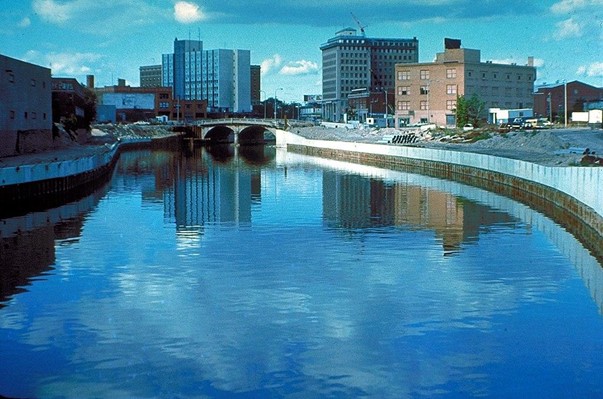

Flint, Michigan, was once a bustling city, home to a plethora of automotive factories that employed much of its population. People once asked, “How close is Flint to Detroit?” They once laughed at the fictional Flint Tropics in the movie “Semi-Pro”’ with Will Ferrell. Some remember when director Michael Moore featured Flint in his 1989 documentary “Roger & Me.” But now, their city is best known for the Flint water crisis, which has faded from the headlines, but has been going on since 2014.

Teacher Pat Cavette described growing up during Flint’s heyday. “Flint was one of the top wealthiest cities in all of America for many years,” Cavette said. “General Motors was founded downtown in 1908, and Flint later became the second-largest city in Michigan. So, it had everything we needed just as most other large towns — excellent school system, well-paying jobs, entertainment, amusement parks, numerous high schools to attend.

“When I was growing up, everybody was employed and making middle-class income or higher. Flint also produced many college professionals and even many Olympians. Flint had a lot of positives going on.”

This is not to say that Flint is without its positives today. Flint is home to many community colleges with downtown campuses for the University of Michigan and Michigan State University. People also make use of the job corps facility where they learn useful trades, the local planetarium, the Black-owned Comma Bookstore and the Flint Institute of Arts.

However, the Flint water crisis has left a stain on the city’s once shining reputation. In April of 2014, Flint’s water source was switched from Lake Huron to the Flint River. Residents were apprehensive. They would only fish recreationally at the Flint River, throwing anything they caught back in the water. The smell of the river was sometimes so putrid that they considered the fish unfit for eating.

Former Flint Mayor Karen Weaver remembers her reaction to the news that Flint would get its water from the river. “We grew up knowing that everything was in that river — from grocery carts to bodies, all kinds of stuff,” Weaver said. “I remember telling my husband, ‘We need to get bottled water, because I don’t want to drink that water.’”

Though the news was not well received by residents, the plan proceeded and Mayor Dayne Walling, who was under an emergency manager appointed by then-Gov. Rick Snyder, pushed the button that would initiate the change.

Three months later in July, the city issued a boil water advisory, which was not just a one-time event. In the fall, Flint’s General Motors plants had stopped using tap water, because the high levels of chlorine were corroding engine parts. By the start of 2015, residents were being vocal about the discoloration that left the water yellow. The material used to treat the water had corroded the old lead pipes, and that material then got into Flint’s drinking water.

Weaver ran against Walling during this time and won.

“I had been volunteering on someone’s campaign,” Weaver said, “and seeing that we were under an emergency manager, I wanted to run to get involved.”

“A lot of people don’t know that our first issue was that our water rates had been raised illegally. We were paying eight times the national average. I went into office knowing we had poisoned water, but when I started running, we were talking about the cost of the water.”

Then-Mayor Weaver declared a state of emergency, a sharp contrast to the previous administration, which insisted everything was fine with the water. But by then, there was no denying that something was indeed in the water.

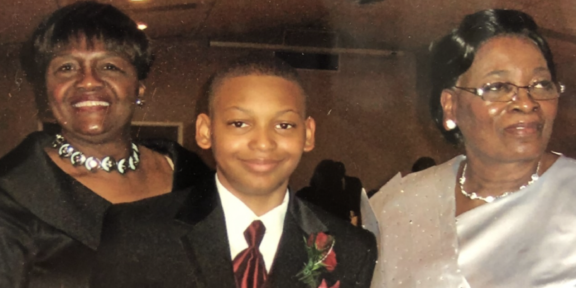

People were breaking out into rashes after taking showers, developing Legionnaires’ disease (a severe form of pneumonia) and complaining of a smell coming from the tap water in addition to the yellow discoloration. Perhaps worst of all, Flint’s children were showing signs of lead exposure, which can lead to cognitive disabilities and other health issues. This is still an ongoing problem, because lead exposure takes years to manifest, and no amount can be considered safe.

“Not only did we have a water crisis, we had a public health crisis, an infrastructure crisis and an economic development crisis — everything was happening at once,” said Weaver, who is running again for mayor. “We wanted to identify those kids, so they could get the help they needed. We knew our special education rates were going to go up, because the damage had already been done. But we wanted to make sure that we had the services in place those families deserved as a result of the damage that had been done.”

To Weaver’s point, the number of students who were eligible for special education went up, according to Education Week. The percentage of special education students has increased by 56 percent, rising from 13.1% in 2012-13, the school year before the water crisis began, to 20.5% last school year.

“Flint was left hanging by local, federal and state governments to solve the issue still yet to be solved, and generations will pay for what’s been done,” teacher Pat Cavette said.

In November, Flint residents were awarded $600 million in a lawsuit, but the lawyers for the plaintiffs were seeking about $200 million in legal fees. This is the most recent lawsuit, and Flintstones are adamant that it is not enough.

“You have 80,000 to 100,000 people who are supposed to split $400 million; that’s not that much money,” Weaver said. “Seniors who lost life and limb and those who suffered stillbirths and miscarriages due to the crisis, what do they get? People who died from pneumonia brought on by Legionnaires aren’t even included in this lawsuit.”

Almost 200 miles west of Flint, another predominantly Black community is also experiencing the hazards of old lead pipes. Like Flint, Benton Harbor, Michigan, has suffered in obscurity. The lead limit in its water has exceeded EPA regulations for at least four years. Residents have filed a lawsuit against Gov. Gretchen Whitmer and other officials for “indifference,” seeking class-action status.

“They should’ve had access to bottled water, testing and other necessities three years ago, and they should’ve known how to do that based on what happened in Flint,” Weaver said of Benton Harbor.

“In Flint, they wanted to do the predictive model, which is ‘with 90-95% accuracy we can say that the neighborhood has copper pipes,’” she explained. “So, you’d find seven houses with copper pipes, but the last one would be lead pipes. If we had gone with that model, we would miss families, so we did not do that.”

“They didn’t even want to dig, but we said, ‘No, we have to know.’” That meant performing hydrovacing, which is essentially using hydro evacuation to dig a hole to determine the type of metal in a pipe. Weaver recalled that once a worker found that a pipe wasn’t actually copper, but a lead-lined pipe that had been repaired with copper. She is adamant that the people in Benton Harbor should be aware of such factors.

“We want them to know how do you get water credits, how do you demand higher water quality standards, because Flint is a blueprint for exactly how to handle that, a blueprint that they did not use,” she said. “As you seek to build trust, try to hire people from Benton Harbor as much as possible.”

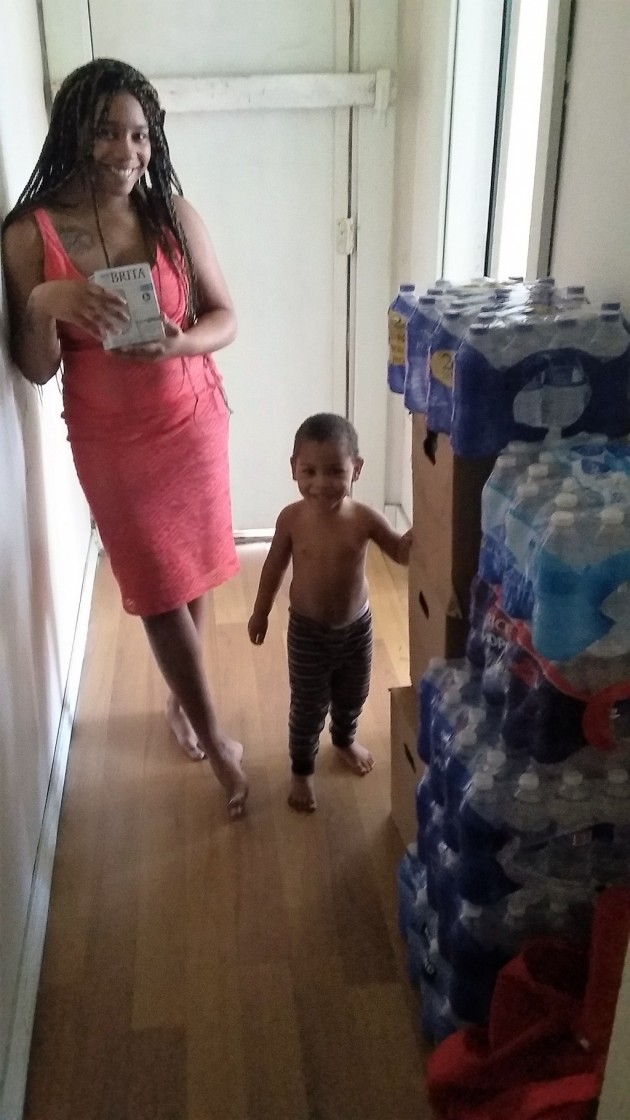

In Flint, people wouldn’t open their doors to receive water from the National Guard. Instead, officials hired young people between the ages of 16 to 24 to give out water and food. Residents decided that they needed to be part of the solution.

“It was healing for us,” Weaver said.

Jaylen Williams, who grew up in Flint, Michigan, is a reporter for HUNewsService.com. His article was a finalist for a Hearst Award for explanatory reporting. It has been updated for the Breathing While Black Project on environmental and climate issues.