WASHINGTON (HUNS) — Every week during lunchtime at Thomson Elementary in Logan Circle, a line of students moves through the hallway on their way to a bright yellow room tucked beside the cafeteria. Instead of heading outside for recess, they step into a space filled with color, soft chatter and a long bookshelf stocked with stories they choose themselves.

It is where Power Readers meet, a program created by Everybody Wins DC that pairs students with volunteer mentors for one-on-one reading sessions. Staff at Thomson say the sight of children rushing in to pick a book and settle beside a mentor is a small but powerful reminder of progress in a city still struggling with low literacy rates among Black students.

For most third graders there, lunchtime usually means lining up for food, eating with friends and then heading to the playground for recess.

Instead of staying in the cafeteria, 8-year-old Lo Jean heads to a classroom filled with colorful books and chooses to spend time with her Power Readers mentor, Talia Ford, or Ms. Talia – as the children call her – who also serves as the programming manager at Everybody Wins DC.

This particular session was unique. Another student, Johnathan, found himself without his usual mentor so he joined Lo Jean and Ms. Talia in their reading group.

Lo Jean was more than happy to let him in on the story, animatedly summarizing the twists and drama of their current book ‘Dork Diaries: Tales from a Not So Dorky Drama Queen.’

Johnathan listened closely – his curiosity growing as Lo Jean described the plot’s most dramatic moments.

“Lo Jean and I gave him some context about the book we were reading and he was like, ‘This is juicy!’” Ford laughed.

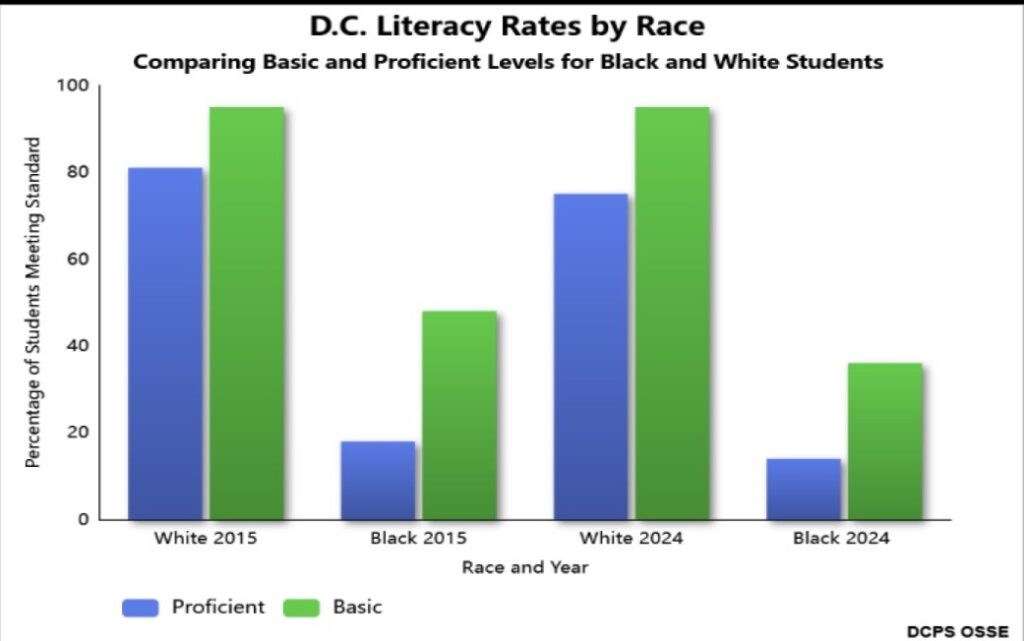

Analysis by the Washington Post in 2019 showed about 27.8% of Black children in D.C. read at or above grade level on the reading exam part of the Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers (PARCC) test, compared with 85 percent of white children. Today, just 27% of Black students in the District are proficient in English Language Arts, according to the 2025 assessment by the D.C. Office of the State Superintendent of Education.

Efforts to boost Black literacy in D.C. stretch back to Reconstruction when newly emancipated residents saw education as essential to full citizenship and self-determination. Over the decades, Washington’s Black community built a legacy of learning in Freedmen’s schools, church-run night classes and community institutions.

For generations, Black Washingtonians have viewed literacy as a foundation for economic mobility, civic engagement and personal freedom.

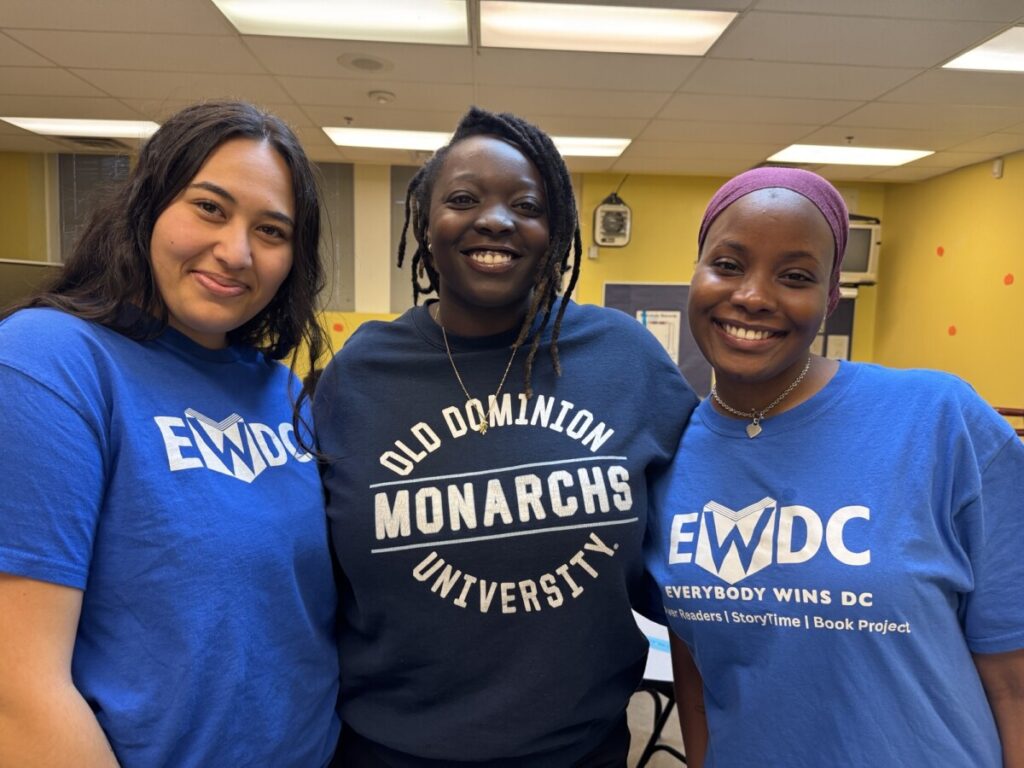

Yashika P. Okon, senior program manager at Everybody Wins DC, said that is where Power Readers fills a critical gap.

“I think that the classroom setting is important but I also think that the one-on-one setting is important as well so that the student can understand that there is a difference in how I need to behave, how I can engage and that this particular person is focused on me and that is what I need,” Okon said.

That legacy continues today in schools like Chisholm, J.O. Wilson and Thomson where teachers, librarians and community partners are working to close literacy gaps that have persisted for decades. In neighborhoods like Ward 7 and Ward 8 where resources are scarce and reading proficiency remains among the lowest in the city, programs like Power Readers are a lifeline.

At schools like Thomson—where many students speak English as a second language or come from households with limited literacy access—there is need for one-on-one reading support. Teachers and staff often rely on programs like Power Readers to provide students the extra attention that classrooms cannot. These individualized sessions help build fluency and confidence for students who might otherwise fall further behind.

“We make sure that everything we give them is free of charge,” Okon said. Access to books, mentors, and consistent reading time becomes the difference between students who fall behind and students who discover the joy of reading.

This broader context becomes essential for understanding why schools across the District rely so heavily on community based reading programs. In the District, the literacy rates vary depending on the ward the students live in. Wards in D.C. are all funded by the citywide government budget; however, not all have the same level of resources for learning as others.

The District implements a Uniform Per Student Funding Formula (UPSFF). In 2025, UPSFF provides about $13,000 per student. This amount is multiplied by the number of students in the school to determine how much funding the school receives. The city gives additional funding to schools that have more students with disabilities, students from low-income households, among others.

However, even with the same UPSFF funding, not every school in the District has the same access to high-level education because higher-income schools use their funding on advanced classes, new technology and college counseling which impact learning directly.

DCPS allocates school funding through a per-pupil model that links each school’s budget to its projected enrollment. The district assigns a dollar amount per student and multiplies it by the expected number of students, which determines how much local funding a school receives. Because the formula influences staffing, intervention programs and classroom resources, shifts in enrollment can have a direct impact on the support schools can offer developing readers.

On the other hand, lower-income schools use their funds on hiring new teachers, attendance coordinators and special education aids. They are not able to spend their money on enrichment programs for the students and instead have to spend it on necessities.

Additionally, poverty plays a role in learning ability. Unreliable housing, food shortages and trauma can all make it harder while a student in a stable environment does not have to worry about such issues. They can focus all of their attention on learning and learning only.

According to the OSSE, in English Language Arts (ELA) Performance Levels—when looking at students who are economically disadvantaged—36.6% of them did not meet expectations. On the other hand, for students who are not economically disadvantaged, only about 16% of them did not meet expectations. That is a 20% difference and further proves how much of an impact socioeconomic status has on students’ ability to learn.

In order to get those who are disadvantaged up to speed, one on one or small group tutoring – or High Impact Tutoring (HIT) – was introduced to give those students more attention.

Power Readers depends on volunteers who work with elementary school students for at least one hour a week practicing their reading skills.

The sessions are in an environment where the students can make mistakes and learn without being embarrassed in front of the class or discouraged.

Thomson joins other schools in D.C., including J.O. Wilson and Chisholm, who benefit from their programming.

The literacy challenges students bring into the classroom are often rooted in gaps that start early and especially in areas such as comprehension, morphology and decoding.

Fourth grade English Language Arts teacher Cierra Barnes sees these gaps every day and connects them directly to the impact of socioeconomic status.

“Parents’ economic status affects their ability to buy books or resources, and that can create gaps,” Barnes said.

She believes access matters long before a child steps into her classroom.

“Demographics do impact students’ literacy,” Barnes said. “Some kids do not have books at home or share a room with siblings which limits access.”

Barnes said these barriers show up in her students’ reading habits and confidence. Many arrive without decoding skills or comprehension skills.

“One big challenge is decoding which is being able to take apart words to figure out what they mean,” Barnes said. “Another challenge is morphology—looking at prefixes and suffixes to understand bigger words. Some students read fluently but struggle to understand what they are reading.”

Power Readers said they change that trajectory by giving students one on one time that does not always fit into the school day.

For many of Barnes’ students, this is the first time an adult focuses attention solely on their reading development.

“Power Readers expose children to literacy and stories, wanting to read,” Barnes said. “You have students who never pick up a book during the school year, but during Power Readers they are super excited to read and connect with someone older over a story.”

That enthusiasm has shifted the culture of reading at J.O. Wilson. Students begin to view themselves differently once they have a mentor beside them.

“It gives students the confidence to pick up a book when no one’s looking,” Barnes said.

She sees the difference even during class activities.

“Power Readers makes students confident, especially during read alouds or popcorn reading,” Barnes said. “Students who typically might not raise their hand even want to participate.”

She said much of this growth comes from choosing stories that reflect the students’ experiences. Cultural relevance makes reading feel personal instead of like a chore.

“Students are most engaged with culturally relevant stories,” Barnes said. “If I have four Black boys, I might pick a book about Stephen Curry or topics they can relate to. This exposes children to literacy and stories making them want to read.”

The connection between students and mentors reinforces identity alongside skill building. Barnes said the program helps students see a path forward especially for those who lack reading support at home. Students in under-resourced neighborhoods often do not have quiet spaces to read or adults available to help. Power Readers fills those gaps by giving students a reliable reading routine and someone invested in their growth.

The impact shows in the numbers. Between 2022 and 2024, J.O. Wilson recorded more than a 10% increase in literacy rates after Power Readers was implemented.

In Ward 8, where many students face financial challenges, the proficiency rate is 13 percent. The results at J.O. Wilson shows what consistent support can do.

Barnes believes the program’s strengths come from more than the curriculum. It is the individual guidance that changes how students see themselves.

“I would add more mentorship,” Barnes said. “Power Readers should include partnerships so students have someone they can look up to and feel comfortable asking questions.”

She views the program as a tool for building readers who feel proud of their progress and eager to learn. For her, change happens gradually but meaningfully. One book, one mentor and one student at a time.

Across D.C. schools, one-on-one support is one of the clearest indicators of whether a struggling reader can make meaningful progress.

High impact tutoring has emerged not as an extra service but as a necessary part of how students catch up, stay engaged and build confidence in their ability to read independently.

Teachers and school staff see the impact in real time especially among students who have faced the steepest barriers to early literacy.

The classroom reveals the limits of what even the strongest teachers can do when time is short and every student needs something different. Large groups make it hard to pause, reteach or work through the small steps that lead to reading fluency. That is why one-on-one reading has become central to how schools approach literacy recovery.

Barnes sees that difference as soon as students have space to slow down and practice.

“Some students can sound out the words without actually making sense of them,” Barnes said. “You start to see the progress when you can sit beside them and break things down at their pace.”

Because foundational skills vary so widely, direct attention changes the pace of learning. Barnes said the individual setting allows students to ask questions they may avoid in class.

“When it is just the two of us, they are willing to stop and say they do not understand something,” Barnes said. “That honesty is what helps them grow.”

That support also transforms how students view themselves. Many who once hesitated during class reading activities begin to participate with more ease.

“You can see the shift,” Barnes said. “Students who were quiet during group reading start volunteering because they feel prepared.”

The interest begins with something small such as a story that resonates or a character who reminds them of home.

Barnes said culturally relevant books make a noticeable difference.

“When students see pieces of their own lives on the page, they lean in,” Barnes said. “It gives them a reason to care about the story in front of them.”

Lauren Dunn, a librarian at Chisholm Elementary who has worked directly with Power Readers for three years, sees the same response in the library. Students gravitate toward the setting because it feels like a space built for them. Some ask to join the program after seeing classmates return excited from sessions.

“Students tell me they enjoy having someone who listens only to them,” she said. “That kind of attention is rare on a busy school day and they value it.”

After working for a program like Power Readers, Okon sees one on one reading as a direct response to gaps schools cannot always fill.

“Teachers manage many responsibilities and individualized time can be hard to provide,” Okon said.

She believes students benefit from learning how to engage differently in these sessions.

“A focused space teaches them how to slow down, ask questions and connect with the text,” she said.

Part of the program’s success, Okon said, comes from removing financial and logistical barriers. Books and materials are fully covered so students can participate without worrying about an additional cost.

“We want every child who needs support to receive it,” Okon said. “No student should be left out because their school cannot afford more books.”

Early literacy has become one of the most urgent challenges facing D.C. schools and educators say the issue is no longer confined to test scores.

It shows up in confidence, classroom participation and students’ sense of belonging as readers. Across the District, teachers describe a growing divide between students who receive consistent reading support and those who do not, a gap that has widened since the pandemic.

At Chisholm Elementary, Ms. Dunn said she sees the effects every day.

“Some students walk in already believing they can’t read well,” she said. “You see it in their shoulders and how they hesitate before they open a book.” Those moments often determine whether a child leans in or turns away from reading altogether.

For students who are behind, classroom time alone is rarely enough to repair those gaps. Teachers juggle pacing guides, large class sizes and varying skill levels, which makes one-on-one instruction difficult to sustain.

“There are days when I wish I could sit with each student for 20 minutes just to slow down with them,” an early literacy teacher said. “But the reality is the school day moves fast.” Librarians and literacy coaches echo that sentiment.

Without additional support, many students continue moving through grades without the foundational skills they need.

The emotional barriers can be just as steep. Students who struggle with decoding or comprehension often feel embarrassed to read aloud or ask questions. Ms. Dunn said that stigma builds over time.

“Kids learn very early who the strong readers are,” she said. “By third grade a lot of them already think they are behind everyone else.”

Programs that offer individualized attention help shift that narrative. When adults focus on just one child, she said, students begin to trust the process and themselves.

“Reading every day with someone who can guide you builds habits that stick,” Dunn said. “That steady rhythm is what strengthens early readers.”

Power Readers operates through small, intentional rituals that turn reading into something personal rather than instructional.

One of the clearest examples is what students find inside their books.

“I, or volunteers, come in, and they just put a stamp in the book along with a note,” Ms. Talia said. “Our notes are something specific that we all do for programming so whenever a student gets a book, whether that is through their free library or book distribution or whatever the case is, the book will have a note from a volunteer just to encourage them to continue their reading journey.”

These messages are short, often just a sentence or two, but they become reminders that someone is paying attention to what the student chooses and how they are growing as a reader.

That level of care extends to the work that happens behind the scenes. After sessions wrap up, Ford returns to the office where she and a coworker sift through new titles from Bookshop and Scholastic, making sure the carts students pull from stay full.

On this particular afternoon, she said, they were focused on stocking Thomson’s shelves. The school currently has 40 students in the Power Readers program, which means new books cycle through faster than they can reorder.

“Our books are getting run through pretty quickly so our main goal today is to find what books we are going to start adding to the cart so that they feel sufficiently stocked,” Ford said. The program runs with a small team, and every decision is purposeful. “Our team is only six people deep, but we do a lot of insightful work,” she said.

That insight shows up in how they select and categorize the titles students see.

“All of our bookshelves are categorized by things like grade, chapter books, graphic novels, etc.,” Ford said.

The choices are not arbitrary — they reflect what students actually gravitate toward.

“A lot of our students love graphic novels,” she said. “A student told me that they love graphic novels because they can tell who is talking, and so I feel like that helps bridge the gap between what we see literacy as and what they do, and it really just helps us support them and see what type of books they want to see on the cart and what they genuinely enjoy reading.”

For many students, being able to follow a story visually makes reading feel approachable instead of intimidating.

In the last year, Power Readers expanded that approach through Power Readers Monthly Activity Books, themed sets that encourage students to explore reading beyond the classroom routine.

The selections are tied to moments in the calendar and cultural celebrations.

October included “Creepy Crayon,” Literacy Month featured Stacey Abrams’s “Stacey’s Remarkable Books,” Indigenous Month highlighted Autumn Pelter’s “Water Warrior” and Social Justice Month introduced “Waiting for the Biblioburro,” a story selected to help students think about activism and the importance of representation in February, which centers Black history and community.

Even with curated offerings and organized carts, the core value of the program is student choice.

Students select what they read and how they spend their time during sessions. It is an approach rooted in respect.

“We give students a choice in picking out their books and what they would like to do during our sessions because, to me, giving respect to our students and how they are choosing to spend their time with us is the utmost important,” Ford said.

The structure is simple but powerful. When students feel trusted to choose their own books, they engage more deeply and see reading as something that belongs to them rather than something assigned.

These efforts also connect to a longer history of literacy access in the District. Unlike much of the South, by 1830, African Americans made up 25% of D.C. and most were free before the Civil War.

According to data from the National Assessment of Adult Literacy, with a staff of Black teachers and some white Northerners, literacy rates among Black students and residents jumped from 20 % to 70% by 1910. 1865 called for the end of slavery and the uprising of the Freedmen’s Bureau for education efforts and community-led training. The bureau educated over 100,000 people despite the limitations of being underfunded and understaffed.

Importance of Literary Access

Greeting students at Chisolm is the school’s librarian, Ms. Dunn. Her love for reading and teaching growing up nurtured the career she one day chose.

“Literacy access is something I’m really passionate about and why I became a librarian,” Dunn said. “I saw a need for more librarians and it’s been a big part of my life to encourage kids to read and build a culture around literacy. It’s my purpose.”

School librarians are well intertwined in daily educational efforts in the classroom. From teaching students how to use literary and technological resources to assisting teachers in finding materials for classroom instruction, librarians play a crucial role.

Ms. Dunn has an open-door policy for all Chisolm students and she says the kids do not take it for granted. At the elementary level, librarians are often seen as mentors outside of the classroom. The job encourages them to curate books of interest—with either less or more pictures—that match with the students’ reading levels. Additionally, librarians reinforce early literacy skills like vocabulary, fluency and comprehension.

However, the amount of librarians, like Ms. Dunn, continues to deplete as the years go by. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, 86% of public schools nationally had a librarian from 1999 to 2000.

Right now in D.C., nearly half of public schools do not have a librarian.

Visits to the school library are on the list of things students have to do at least once. Whether those stops in the space included chatting with the librarian, finding a quiet place to study or buying a ‘Dork Diaries’ book from the Scholastic Book Fair, the experience of the space is unique to most students.

The program has made kids excited to read again. The sessions also improve confidence for when it’s time to read in front of the class or read for a presentation. Keeping them engaged and interested is key in continuing to improve literacy rates.

“We just go off the vibes,” Ford explained and flipped through the ninth Dork Diaries book with a cheetah print-sleeve. “Today was both fun and insightful. They asked great questions and made some really thoughtful observations.”

Watching Lo Jean and Johnathan together showed how much the program grows naturally from the kids themselves.

As they picked up where they had left off which happened to be page 165, Lo Jean took the lead confidently reading aloud and discussing each section with Ms. Talia who prompted her to dig deeper.

“Can you explain what the Miss Know It All column is to Jonathan?” Ford asked.

Lo Jean immediately broke it down for him. She also made connections to her own life. She laughed about Nikki, the protagonist, having a spoiled little sister then admitted, “I consider myself the spoiled little sister too,” because she is the youngest with two older brothers.

In this session, the group explored literary tropes examining how MacKenzie, the antagonist, fits the familiar ‘rich girl’ character type. For Lo Jean, recognizing tropes gave her more insight into why MacKenzie acts the way she does and why her rivalry with Nikki keeps the story moving. Johnathan added his thoughts and the conversation flowed with their shared opinions.

Conversations, connections and further learning tend to spark in interactions like these—and the increase of resources, librarian support and mentors could be a starting point. However, this information is not brand new.

One in every four D.C. adults struggle with basic reading. The effects of this ratio shrinking could result in increased poverty rates, workforce displacement, homelessness or a decrease in school enrollment. Though it was not always like this.

The National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) reports that the city’s reading score gaps were smaller between white and Black people in the 1980s and they were almost reading on the same level.

This increase was studied and attributed to federal education programs like Chapter 1, or Title I. At the time, the scores of voluntary Black test takers for the NAEP and SAT were expected to go down despite them being the majority taking the assessment. However, their reading scores increased by 30 points while white test takers’ scores increased by only two points. This was the same year the Civil Rights Act passed the House and Senate.

Today, Black students continue to go through events that are documented in history books from COVID-19 to the longest government shutdown in U.S. history. The written passages would not have meaning if no one is able to read them in the future. Based on the recent data, the future is closer than some might think.

Magic wands or comic book superheroes aren’t necessarily coming to the rescue to help students increase their engagement with literature. Nevertheless, Dunn believes that the brain—like any muscle—needs consistent and focused exercise.

“Practice is at the forefront when it comes to developing strong literacy skills,” Dunn said. “Maybe a student doesn’t have someone that is reading to them after school consistently. It’s important to read beside someone—especially for our early readers.”

In a perfect and fictitious novel, all students have equal access no matter what their background is. Elizabeth Ross, the city’s assistant superintendent of teaching and learning, recognizes that this problem is a recurring issue.

“We find that there are significant opportunity gaps,” Ross said. “Our students furthest from opportunities are achieving at lower rates than our students closest to opportunity. That’s something we’re working really hard to disrupt.”

Power Readers is involved in six elementary schools in the DMV and three of them have over 60% of Black students enrolled. Similar to these schools, Black students make up the majority of the city. Despite this fact, they scored 69 points lower than their white peers in the 2024 reading assessment. White students account for 17% of the population.

Throughout history, the education Black people received was shaped by periodical eras like slavery, Reconstruction, Jim Crow, segregation and civil rights activism.

These details offer further context that addresses the limitations that come with educational and literary access for Black Americans.

At the same time, modern challenges continue to shape how students interact with reading.

For Black kids specifically, their culture is a part of the new social media populating app stores and trends. Picking up a book can make them feel disconnected from that and their peers.

As a way to combat this issue, Everybody Wins DC began their Power Readers program. This program focuses on giving every kid more attention.

The intention guiding every moment was easy to see. Ms. Talia is not just a mentor. She is someone who deeply understands how a love for reading takes root.

“My mom is the reason I love books,” she said. “She used to take me to Barnes and Noble, letting me pick out whatever I wanted. I never experienced the Black literacy gap growing up because I was raised by someone who loves to read.”

Her job with Everybody Wins DC opened her eyes to a more challenging reality.

“I have learned that many students do not read at grade level and even more are not reading books they actually enjoy,” Ms. Talia said.

That personal touch was present throughout the session. Ms. Talia revealed that after Lo Jean finishes the ninth book in the Dork Diaries series, there is just one title she has not read yet. Ms. Talia is planning to buy that missing book so they can read it together.

By taking this extra step, she said she is showing Lo Jean that her interests matter and ensuring she can continue reading books outside the classroom that she genuinely enjoys. After finishing the series, Ms. Talia plans to introduce her to ‘Curlfriends,’ a graphic novel featuring Black girls with natural hair.

“Lo Jean has curly hair and I have locs,” Ms. Talia said. “We should focus on representation so she can understand the relationship between hair and Black girlhood.”

Choosing stories, for her, is thoughtful and meant to reflect Lo Jean’s life so that reading feels fun and not like a school assignment.

Instead of waiting for a whole class to catch up or struggling to get attention, Lo Jean and Johnathan received personalized instruction, personal discussions and gentle challenges tailored to their literacy journey. Literary terms like protagonist, antagonist and common tropes became easy to understand and remember.

They were able to relate stories to their own lives and understand reading not just as a skill but as a way of making sense of themselves and the world.

By the end of the session, the confidence and camaraderie had grown. Lo Jean showed more initiative and Johnathan’s interest in the story had turned into excitement.

Faith Harper, Will Armstead, Rasiah Worthy and Grant Roundtree are reporters for HUNewsService.com