WASHINGTON (HUNS) — In July 2024, Anthony Antrum-Frank became the guardian of his grandson, bringing him into his home in Upper Marlboro, Md., after the child had been living in a car in Connecticut with his mother and five siblings.

As a new guardian, Antrum-Frank began noticing small behaviors and sentiments from his grandson that worried him.

One day in particular while he was playfully horsing around with his grandson, in a fighting stance, he saw something shift in his eyes.

“[My grandson] was really trying to hurt me,” Antrum-Frank said. He understood his grandson likely developed pent-up aggression and that he needed a positive outlet to handle his emotions.

Just two days later, while getting a haircut, Antrum-Frank noticed the barber next to him wearing a graphic T-shirt with Gary Russell, a Washingtonian professional boxer, that read “PAL Connect Boxing.” He asked about it and that conversation introduced him to the Connect Boxing program at the Prince George’s County (PGC) Police Athletic League.

The PGC Police Athletic League, known as PAL, works to build trust between youth and law enforcement through mentorship and community-based programs. Its approach reflects a broader national effort to reduce juvenile crime through early intervention, engagement and opportunity rather than enforcement alone.

PGC PAL also offers sports programs, including Connect Boxing, where youth like Antrum-Frank’s grandson train weekly and compete in local matches.

“Since he’s been in the program, he has friends outside of school. The camaraderie he’s built here is paying dividends,” Antrum-Frank said.

Antrum-Frank’s grandson knows his coaches are police officers in their day-to-day jobs; their authority carries more weight when it comes to discipline and behavior outside of boxing.

When his grandson got in trouble at school, the first thing Antrum-Frank told him was, “You know, I have to tell coach.”

Antrum-Frank explained that his coaches were like family — and family needs to know what’s going on so they can help.

“I explained that to him, and sure enough, Coach had a little talk with him. That’s just what he needed, [because] sometimes coming from me, the parent, it doesn’t register the same,” he said.

PGC PAL is one of over 300 chapters across the nation, serving over 2 million kids annually.

PAL’s roots trace back to 1914, when former Police Commissioner Arthur Woods of the New York City Police Department (NYPD) introduced Play Streets, a program that closed sections of city streets so that youth from crowded neighborhoods could play safely outdoors.

These supervised play areas set the foundation for a bigger mission.

By 1917, the initiative evolved into an official nonprofit entity. Its early mission focused on providing structured recreation to prevent delinquency while improving relationships between youth and police officers.

The organization now runs early childhood education centers, teen juvenile re-entry programs and youth employment initiatives across the five boroughs.

PAL’s emphasis on sustained mentorship rather than short-term interventions remains key to its success.

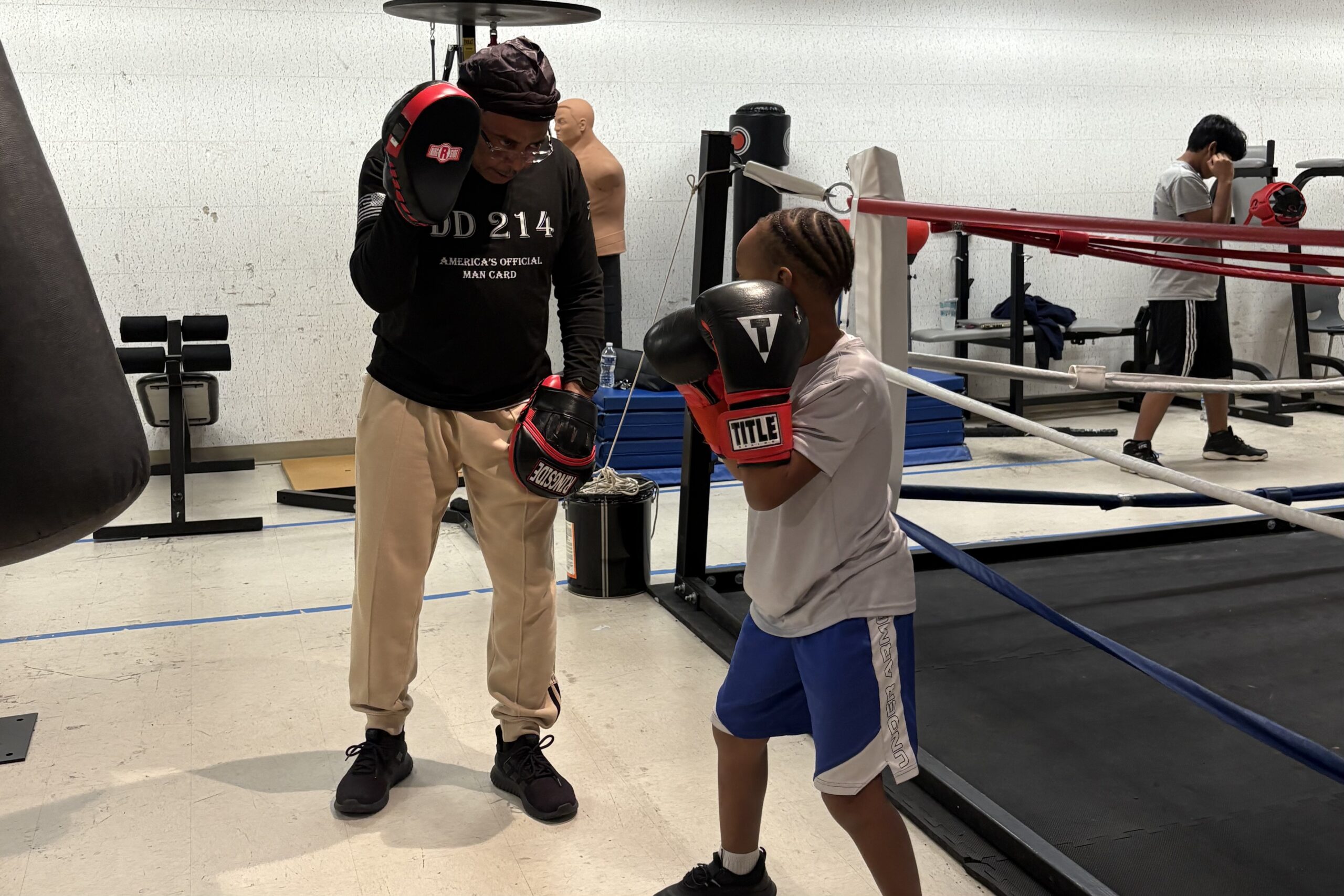

Connect Boxing practice starts with the kids stretching in the middle of the ring. Thirteen-year-old Christopher Escobedo leads the group, preparing for their upcoming matches.

Escobedo is finishing his first year of boxing, but said he already sees changes in himself and his work ethic.

“PAL helped me get my grades up, get my discipline up and respect all my elders,” he said. “Back then, in sixth grade, I had bad grades — C’s, some D’s. But ever since I joined this program, I have straight A’s.”

After encouragement from family friends, his parents wanted him to try boxing. Escobedo enrolled and said the sport hooked him immediately — he loves the thrill.

He continues coming to practice and working toward bigger matches because of his friends and the relationships he has built with his coaches.

Although improving in boxing excites him, he loves the community the most because they’re “so nice and loving.”

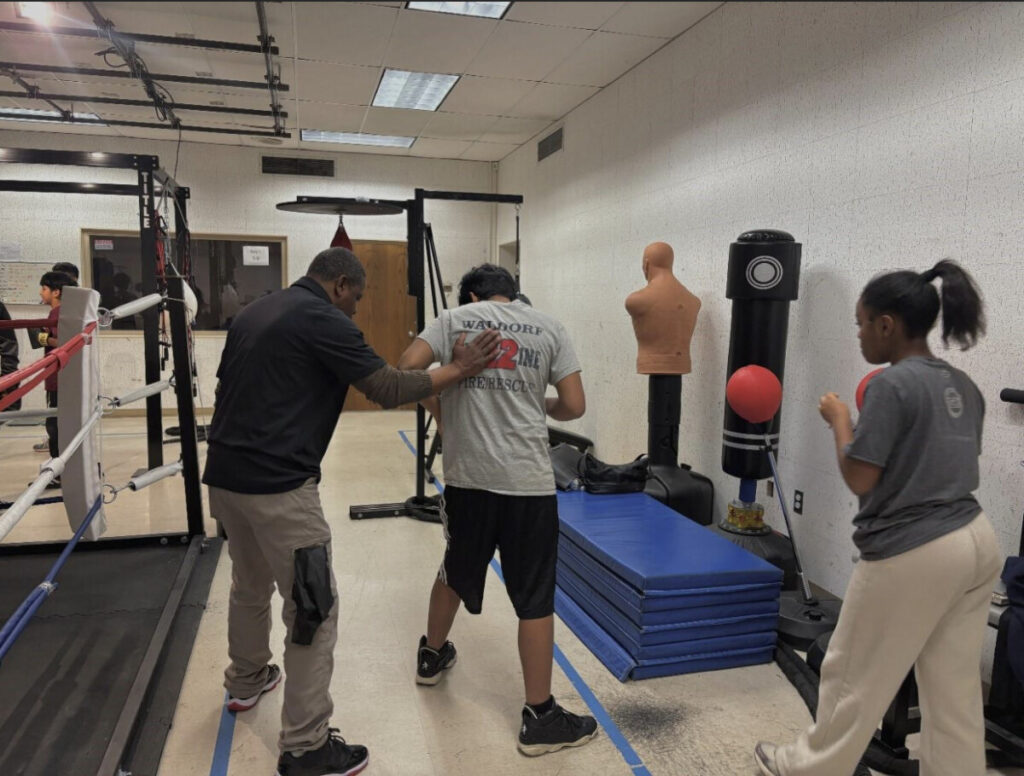

During practices, coaches guide each station: some kids hit bags and dummies, others jump rope, and a few work on hooks, jabs and punches under their coach’s supervision.

With the leadership of Cpl. Pierre Boone and his longtime boxing mentor, Coach Gregory Lowery, the PGC PAL Boxing Connect League is a growing outlet for youth looking for guidance, structure and community outside of their everyday environment.

Boone grew up in Southeast Washington, D.C., where stability, he said, was hard to find.

With a mother battling addiction and no father present, he found direction in the one place that demanded discipline and built confidence; the boxing ring.

He started training at age 12.

“Boxing played a major impact on my character building, leadership and discipline,” Boone said. “I got inspired when I was with the police agency to help the youth within the community, bringing my specialty to help get their attention.”

Boone is currently in his 18th year of service as a PGC officer.

He was in the pursuit of becoming a professional boxer, consistently training, as that’s what he believed was his life’s calling. However, his childhood best friend, Donnell Jones, was killed due to street violence, including additional friends throughout his life.

“I wanted to do something honorable and give back in a way to prevent someone else from feeling the exact pain that I felt losing a best friend,” Boone said.

Along the way, Boone had mentors who suggested he start filling out applications, encouraging him to fully pursue becoming a police officer.

“I applied for different agencies in Prince George’s County police agency. They accepted me faster than the other agencies,” Boone said. “And here I am today using my platform to help kids and through the sport of boxing have a connection with my community.”

Much of that foundation came from Lowery, now 63, who coached Boone throughout his childhood. Lowery was the mentor who picked him up from the neighborhood, kept him focused and made sure he stayed committed to something bigger than the environment around him.

Boone credits him for shaping his confidence and sense of purpose.

“He used to come around the hood, in Southeast and pick me up for boxing practice,” Boone said. “I stuck with his mentoring boxing program all the way through high school and afterwards.”

Lowery’s influence traces back to his own early start in boxing at 10 years old.

He never became a professional boxer, but he poured his skills into mentoring kids in Southeast. While coaching, he focused on volunteer initiatives and creating a safe space for young boxers like Boone.

“He just stuck to me,” Lowery said. “I considered him my son. I tried to school him on everything I could. He made something of himself coming from the hard part of D.C., passing all the drugs, and becoming a PG cop.”

Before joining Boone as a PGC PAL coach, Lowery survived a traumatic turning point in 2020 when he was shot five times at a barbershop in Northeast Washington.

The shooters were juveniles, and the experience left him ready to walk away from coaching altogether.

“It created a lot of fear in me because I didn’t know who the kids were,” Lowery said. “I thought, ‘Man, I can’t save everybody. I’m gonna stop and give up coaching,” but Pierre kept asking me to come help him coach, so I prayed on it, and God gave me a sign to go.”

Today, the two operate as a team, mentor and mentee turned colleagues, passing down discipline, accountability and emotional support to a new generation of young athletes.

“The feeling is better than money,” Lowery said. “I can see I’m leaving a legacy, and Boone is leaving his. It all started with me, and he stayed on the right track.”

Together, they are creating a space where teens not only learn boxing fundamentals but also build character, responsibility and confidence, which are qualities that Boone knows from firsthand experience can change the trajectory of a young person’s life.

“I was one of those kids from a high-risk area, so it’s personal,” Boone said.

Boone expresses empathy for families in his community and said his passion for youth mentorship comes from the heart.

“I’m living proof of what positive mentors and coaches can do. [Connect Boxing] is a village and a family,” Boone said.

Sports Programs Strengthening Prince George’s County Youth

Prince George’s County is home to nearly 950,000 residents, with 22% under the age of 18. The county offers a range of sports activities and nonprofit organizations that keep the youth physically engaged.

Today, PAL serves as one of the largest youth police partnership programs in the nation. According to the National PAL, more than 300 chapters across 38 states serve over 2 million young people annually.

Prince George’s County, neighboring Washington, is the second most populous county in the state, after Montgomery County.

Although the PAL program was officially established as a nonprofit in 2016, records show its presence in the community for decades prior.

While coronavirus was at its peak, tensions between law enforcement and the public were also rising, fueled by police brutality, particularly against Black Americans.

During this time, many perceptions of police officers and their role to protect communities were strained.

As someone who served in the Army for 25 years and has a brother who is a federal police officer, Antrum-Frank said he was troubled by what was happening in the community.

“Given the events that happened since George Floyd, there’s been a stain in my brain about that, because you see the same thing happen over and over and over again,” he said.

Cpl. Robert Boyce, PGC PAL program coordinator, strives to build trust with youth through personal connection and understanding.

“The whole point of it is to really bridge that gap between law enforcement and youth, so they see us in a different aspect and not just from an adversarial, negative point of view,” Boyce said.

Boyce, a police officer for nearly 14 years and a Prince George’s County native, said growing up in the area inspired his decision to enter law enforcement. He now leads PGC PAL’s youth mental health initiative, describing his team as deeply community oriented.

“If we weren’t police officers, you could very well see us being some kind of counselor, social services person, or minister — that’s what it feels like,” he said.

He added that the officers’ approach to working with kids is key. Officers often change out of their uniforms during athletic events, blending in more as gym coaches than law enforcement.

“When we have to put our police hats back on, the kids are surprised: ‘You guys are police officers?’” Boyce said. “They see us more as mentors and coaches than as police officers — and that’s a good thing, because it shows them we’re just people who care about them.”

The Importance of Police-Community Relationships

One in four residents of Prince George’s County is an immigrant and about 100,000 children have at least one immigrant parent, making 83% of them first-generation Americans.

At the age of 17, Mercy Kimeng left Cameroon and started a new life in Prince George’s County.

As a teenager, she saw firsthand the activities youth her age took part in, especially during the summertime.

She also realized that some activities other teenagers were involved in could lead to trouble.

After growing up in this environment, Kimeng noticed, during one summer break, her son befriended peers who were not good influences. A fellow parent introduced her to PAL Connect Boxing.

Through the program, PGC PAL combined her son’s love for boxing while also instilling decision-making skills within his personal life.

“I’m very proud that I found this program for my son because only God knows what could’ve been his life,” Kimeng said.

She noticed the skills learned in PAL Connect Boxing translated to his performance in school.

As he grew into a teenager, Kimeng realized how susceptible kids are to their surroundings.

“He loved to box [as it gave him] some talent and knowledge of being a man, to make his own decisions,” Kimeng said. “Not to be a follower, but to be a leader.”

The presence of PGC PAL in the community gives kids an opportunity to invest their time in sports instead of activities that could be harmful.

“I really wish a lot of police officers [got] involved, not just to patrol the street but to help other kids in the streets, like what [Boone]’s doing,” Kimeng said. “What he’s doing is impacting PG County.”

Boyce said the program aims to help youth make better decisions — and when mistakes happen, officers use them as teachable moments.

“You never know what’s going to stick with a child,” he said. “You just expose them to something positive, and next thing you know, they’re going to college, joining the military, or studying something they were introduced to through PAL.”

This growth is what makes Boyce’s job special to him. He said PGC PAL has earned a strong reputation over time.

“We’re not perfect, but we’re a lot further along than a lot of other departments,” Boyce said. “That’s reflected in our relationships with the community.”

He added that the community is highly supportive of the department and its work, with many residents even having the police chief’s personal phone number.

Boyce also noted that many members of PAL are people of color or come from minority backgrounds, which helps them relate to the youth and share their stories more comfortably.

He said the kids enjoy everything the PGC PAL program has to offer, and that many of them have bonded over shared interests.

“Every one of us has some kind of passion or hobby that we’ve been able to create a program out of, and the kids have benefited from that experience,” Boyce said.

mentoring session. (Photo: Beverly Robertson/HUNewsService.com)

Leslie Recabarren grew up in Silver Spring, Md., an only child, with a mother and father who were always engulfed in work.

As she grew into adulthood, she realized she wanted her kids’ lives to be different.

Her three children — Landon, William and Julissa — have three different personalities: one naysayer who is hard to impress, one extremely outgoing and always the loudest in the room and the other shy and timid, waiting to pop out of her shell.

Recabarren also never grew privy to sports, but with a fiancé who is a fanatic, she was persuaded. She signed her kids up to play basketball at PGC PAL.

While being in PGC PAL activities for three years, her kids are starting to grow into young adults who are learning the value of thinking for themselves — critically assessing situations and going through life with confidence and precaution.

“[The officers] let them be themselves. And I think that’s very healthy, because sometimes that’s all they need. A safe space where they can be themselves [and] also get words of encouragement whenever they need it,” Recabarren said.

Their three different personalities have turned into a unit of confident and motivated youth who can take on the world — and help make Recabarren’s life easier because she worries less about their future, she said.

Through their invested time spent within the program, the Recabarrens started to develop strong relationships and bonds with the coaches, especially with an officer by the name of Coach Davis.

In 2024, he passed away, leaving an emotional impact on the family.

“It’s a very sensitive topic because my daughter used to call him her twin,” Recabarren said. “The reason why that nickname stuck was because they both wore braces, and she used to be self-conscious about her braces.”

Not only were her kids involved in PGC PAL basketball, but they were also a part of the Boxing Connect program, competing in their 2-day competition showcase. Recabarren shared how Coach Davis’ passing tremendously impacted her family.

“He actually bought ring-side [VIP] tickets to my daughter’s [boxing] fight right before his passing,” Recabarren said. “We had a dedicated chair for him with his name in graffiti and put it ringside.”

PAL has lasting effects on youth as they grow up not just in Prince George’s County but in several communities.

Enough so that alumni of PAL now serve in prominent roles that support PAL operations, including Galen Duncan, the vice president of health, wellness and performance at National PAL.

National PAL, based in Washington, provides resources to PAL chapters across the country, including support with grants, funding and training. It also hosts events such as the annual youth summit and develops programming that local PAL organizers can use to enhance their work.

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, the PAL model spread to cities nationwide. Each chapter operates independently but follows the same guiding principle: using athletics as a bridge between law enforcement and local youth.

As PAL chapters expanded, the need for a unified system became clear. In the early 1940s, the National PAL was created to establish consistent standards, train officers and provide a national platform for youth engagement.

National coordination allows chapters to share best practices, measure social impact and expand programming beyond sports into education, life skills and community service.

“PAL has always been on the forefront of creating environments where police and young people can learn from each other,” Duncan said.

Duncan is a product of the Detroit PAL program, which he first joined as a child after visiting an arcade with a friend. His friend was already in the program and introduced him to one of the officers and the basketball coach running it, who invited Duncan to play.

After serving in the Army Reserve and building a career in basketball as both a player and coach, Duncan eventually returned to PAL for a professional role.

“It’s just ironic that I get a chance to work for one of the organizations that I participated heavily in as a young person,” Duncan said.

He spends much of his time overseeing these initiatives and designing new resources to help youth and their communities grow stronger mentally and emotionally.

As PAL continues to evolve nationally, Duncan said the organization works every day to improve its systems and create better opportunities for youth development.

“We’re even getting better at being able to deliver things that other childcare or youth leadership organizations can’t,” Duncan said.

Duncan said the organization’s success is tied to the increased exposure and comfort youth have with local law enforcement.

“It would be great to have people who are emotionally sound, well-trained and understand their communities eventually come back and become police officers themselves,” Duncan said.

He said positive community policing begins with people who care about the safety and well-being of the places they reside in.

With PAL implemented in cities across the country, he said, a new generation is growing up with police mentors and realizing they, too, can give back through public service.

The Shared Goals and Differing Resources of PGC and DC PAL

In neighboring Washington, D.C., the number of juvenile arrests has increased annually since 2020, with more than 2,000 juveniles apprehended in 2023 and 2024.

The Metropolitan Police Department (MPD) is the primary law enforcement agency for Washington.

Taariq Cephas, a sergeant for MPD, is the community outreach supervisor. His role entails supervising community outreach officers in the sixth district. MPD community outreach collaborates with DC PAL to host events for the youth.

In the summer of 2024, a DC PAL youth basketball camp was hosted in Washington.

The annual camp was created with the vision of building camaraderie and trust in the kids, along with “bridging a gap between law enforcement and the community while also teaching [the kids] how to play a sport,” said Cephas, who helped host the basketball camp.

As a child growing up in Delaware, Cephas participated in the Delaware PAL (PAL DE).

Through this experience, he learned team-oriented and leadership skills, engaging in sports such as baseball and basketball.

Cephas credits this experience for teaching him how to be a young adult.

The exposure to law enforcement and athletics that he received from PAL DE influenced the trajectory of his professional career.

“[As] I grew up…a child…participating in the police athletic program, I knew that I did want to be a police officer,” Cephas said.

Once he became an officer in Washington, he noticed that there was no police unit dedicated to PAL and sports.

Through Cephas’ personal experience participating in PAL DE as a kid, he understands the impact the organization can have on a city.

He also views the DC Police Foundation Police Activities League (DC PAL) programs as his opportunity to make an impact on the community of Washington.

“We could bridge the gap between the police and the community through sports,” Cephas said.

PAL helps youth familiarize themselves with police officers on a personal level, seeing them as people, rather than a uniform and badge.

“We try to build positive and healthy relationships between police and youth…to show kids that police are human too,” said Patrick Burke, the executive director for DC PAL.

Along with establishing relationships between youth and police officers, the program uses sports initiatives to keep kids in school and encourage them to maintain their grades.

DC PAL, a nonprofit organization, provides financial and non-cash resources to MPD.

The name of the organization is a non-traditional PAL chapter name, but it engages with the youth in similar ways to PAL chapters across the nation.

“[The name] became a natural fit,” said Rebecca Schwartz, the director of development and operations for DC PAL. “Since we were already existing as the police foundation, we just made [DC PAL] our chapter name.”

Though PGC PAL and DC PAL share similarities, there is one thing separating the two leagues.

“[PGC PAL has] a full division and [the] officers are devoted to those programs,” Schwartz said. “Their schedules permit that they can be devoted to [those] program[s].”

MPD and DC PAL are separate entities, but they often collaborate to host activities for the youth, including sports programs. Unlike PAL programs in other cities, DC PAL does not have a unit where police officers are specifically dedicated to staffing the PAL program.

“To make it short and simple, [MPD is] understaffed as a department,” Cephas said.

According to Sharde’ Harris, the commander of YFED, the youth outreach programs are the closest thing MPD has to its own PAL unit.

DC PAL also does not own a building dedicated to hosting PAL events. Instead, they go to schools, neighborhoods and host events at MPD’s youth and family engagement division (YFED).

YFED is a division of MPD. It partners with DC PAL to offer kids in Washington various activities, including educational and recreational programs.

YFED is made up of three organizational units: the youth investigative branch, the school safety branch and the cadet corps branch.

The school safety branch is responsible for the youth and engagement unit, which has youth outreach programs that are considered PAL programs.

“Some people, when they look at PAL, they think about…athletics,” Harris said. “Our PAL is not just athletics.”

Through offering structured activities and athletic programs, PAL provides the youth with a positive and productive way to spend their free time.

Youth are put at risk of becoming involved in juvenile crime due to a combination of factors, such as their home environment, lack of education and unsafe communities.

Police officers mentor youth through sports and become a support system for kids experiencing hardships in their personal lives, as some are the product of their surroundings.

“Challenges outside of school with neighborhoods that people live in, where there’s susceptibility to violence. Trauma that people see at early ages could cause some really lasting damage,” Burke said.

How Prince George’s County is Handling Juvenile Crime

According to the Maryland Department of Juvenile Services, juvenile complaints referred for intake have dropped by 76.5% since 2010. Officials attribute this progress to local diversion and prevention strategies designed to keep youth out of the system.

“There are many contributing factors… It is cooperative youth. It is more attention to the matter… It is more activities and school,” Prince George’s County Police Chief Malik Aziz told WTOP News.

His comments reflect a broader understanding that youth safety depends on more than policing; it requires consistent community engagement, parental involvement and access to positive outlets.

Maryland’s broader policies have also evolved. A recent state law now allows children as young as 10 to be referred to the juvenile justice system for nonviolent offenses.

At the same time, programs such as Children in Need of Support (CINS) and the Disproportionate Minority Contact (DMC) Committee offer alternatives to detention and aim to reduce racial disparities in the juvenile system.

Altogether, these efforts reflect a growing shift toward prevention over punishment.

Prince George’s County is investing in proactive, community-based approaches, from mentorship programs to youth sports initiatives, that build trust between young people and law enforcement while addressing the root causes of delinquency before they escalate.

Prince George’s County PAL Offering Families a Second Chance

In Prince George’s County, officers and community members say the program is helping the community in multiple ways and at a low cost.

“The whole point is to serve the youth of Prince George’s County and give them a positive outlet that parents may not be able to afford or enroll their kids in otherwise,” Cpl. Boyce said.

Antrum-Frank echoes support about cost and accessibility with PGC PAL, especially when it comes to helping youth in the community.

Like many officers and administrators of PAL, Antrum-Frank was also involved in PAL while growing up in Waterbury, Conn.

He said visiting the barbershop and meeting the woman wearing the Prince George’s County PAL T-shirt felt full circle, especially because of the dedication he remembered from his own coaches.

“My mother didn’t have a car, but they came to pick us up. They really invested in us,” Antrum-Frank said.

He is now entrusting the PGC PAL coaches to help his grandson with his growth and development as a young child, hoping he can build a better life than Antrum-Frank ever imagined for him.

Antrum-Frank’s son grew up in a two-parent household but still struggled and strayed and is continuing to find his path.

With his grandson, he feels that with the help of PGC PAL and support from the community, the child’s future will be different.

“My goal is to not let this one stray, and [his] siblings I have with me right now. It’s like God’s given me a second chance,” Antrum-Frank said. “That’s the way I look at it.”

Brandon Horton contributed to this story.

Armani Duncan, Taylor Swinton and Beverly Robertson are reporters for HUNewsService.com