WASHINGTON (HUNS) – Tucked away in the back corner of L’Enfant Plaza, the District Department of Motor Vehicles Adjudication Services sits apart from the buzz of the mall. Here, people pay or contest their traffic tickets. Outside of the center, barbers fade hair, children run around their parents and the smell of food drifts through the plaza. Inside, the tone is subdued.

The red and grey interior is lined with brown wooden panels and a lone pumpkin wearing a witch hat ahead of the Halloween season. Sighing and groaning, people desperately wait for their number to be called, shuffling paperwork in their hands. An automated voice comes over the speaker, “Now serving B238 at counter 8.”

It’s a familiar scene for many D.C. residents: a quiet room full of people paying for small mistakes behind the wheel.

In Washington, D.C., Automated Traffic Enforcement (ATE) is a leading tool for regulating driver behavior. Over the past few years, the number of cameras monitoring drivers across the District has expanded rapidly — and so have the fines.

The Human Cost Behind D.C.’s Automated Tickets

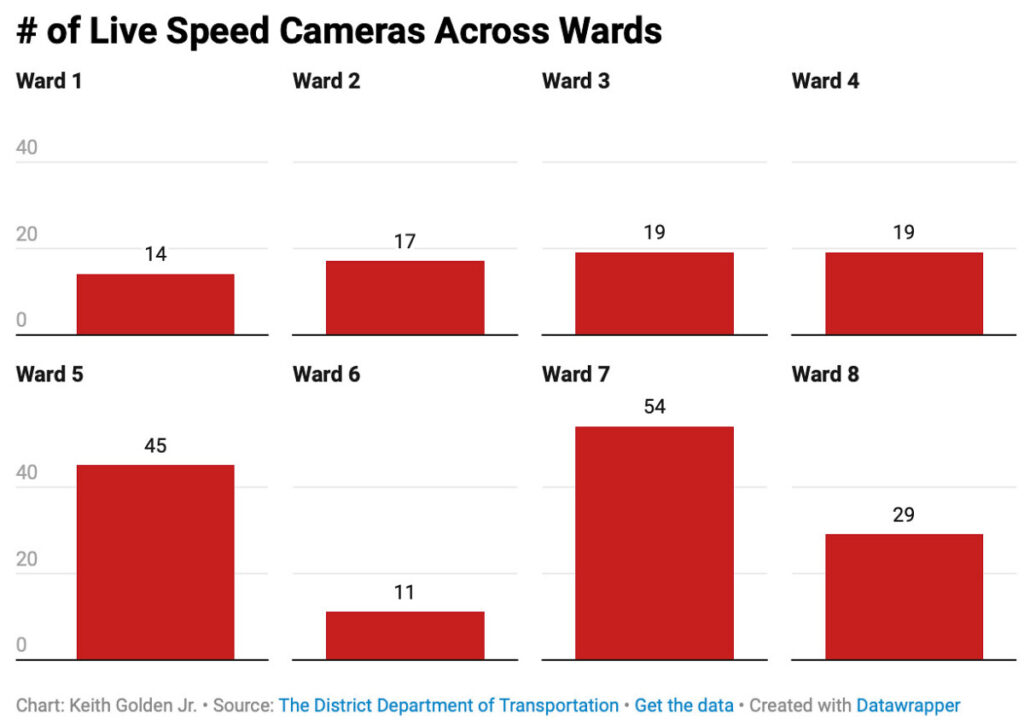

In 2023, drivers and pedestrians could find 145 cameras along the streets of the district. Of that number, there were 109 speed cameras, seven stop-sign cameras and 29 red-light cameras. That number has since more than doubled.

By December 2025, the District Department of Transportation (DDOT) had noted 546 cameras, including those for clear lanes, school buses and truck restrictions.

But the consequences of that expansion have not been felt evenly.

Trisha Nicolas, a resident of Upper Marlboro, Maryland, takes the Suitland Parkway every week to enter the District to do grocery shopping and visit her family. As soon as she crosses into D.C., the cameras are waiting to catch her.

“I’ve paid over a grand in traffic tickets and right now I owe $1,440,” Nicolas said. “It’s scary. Now I’m thinking, when I go to the city, let me be aware of where I park my car, so they don’t tow me. If I ever got stopped in the city, are they going to see that and take my car?”

Her experience is not unusual. From 2016 to 2020, an analysis of D.C. enforcement records by the Washington Post showed 62% of all fines issued by automated systems and D.C. police totaled $467 million. These fines were concentrated in neighborhoods where at least 70% of residents are Black and the average household income is below $50,000.

Predominantly white and more affluent neighborhoods accounted for $95.9 million of those same types of infractions. Revenue data also shows that specific camera sites generate a large portion of the city’s fine income.

In 2025, 88% of the residents in Wards 7 and 8 identify as African American.

Residents who drive through the District say they feel that expansion every day. One non-profit organization is currently rethinking the approach to traffic camera fines and penalties throughout the nation.

Founded in 2018, the Fines and Fees Justice Center (FFJC) said they are dedicated to ending what it calls “the criminalization of poverty.” Referring to the widespread practice of imposing fines and fees across the nation, the group is a leading voice in national debates regarding how cities impose and enforce penalties.

A Movement to End the Criminalization of Poverty

Shanelle Johnson, the senior policy counsel at FFJC, collaborates with jurisdictions to align their policies and practices with the organization’s research on criminal justice fines and fees, as well as traffic system fines and fees.

“ATE is just an automated way of ticketing people. So, if humans ticket Black and brown people disproportionately, cameras that are designed and installed and managed by humans are just a more efficient way to do that,” Johnson said.

The organization attacks the issues of fines through three major approaches: creating an advocacy framework that states can adopt, maintaining a national hub that tracks and shares information for ongoing reform and offers direct support to on-the-ground organizations who are aligned with their mission.

While policymakers debate how to restructure D.C.’s traffic enforcement system, FFJC has emerged as a clear guide for communities searching for accountability. Johnson said the organization has positioned itself as a movement and a blueprint for driving local action.

FFJC maintains national databases, tracks state-level legislation and examines how cities utilize fines and fees to generate revenue. It also produces detailed toolkits that show residents how to uncover local data and document their experiences with disparities.

For cities like D.C., where the government does not fully report its fines and fees data, FFJC attempts to fill a critical gap.

According to FFJC’s national analysis, only 24 states currently report their fines and fees revenue; D.C. is not one of them. The group said the lack of disclosure keeps communities in the dark.

“People need to know how much is being assessed and how much is being collected because that’s really where a lot of this starts,” Johnson said.

She added that in many cases, the issue is not intentional secrecy but structural dysfunction.

“Sometimes it could be governments trying to hide the ball, but I think, unfortunately, a lot of them just don’t know,” Johnson said. “If you don’t have your system set up to track fines and fees in a productive way, sometimes it’s hard to actually figure that out. If your systems don’t have someone dedicated, or it’s not something they’re actively working towards or looking at, it can be hard to say.”

FFJC argues that the national fines and fees total is higher than reported because more than half of the states do not share comprehensive data. The nonprofit estimates that state and local courts collected at least $14 billion from fines and fees. FFJC believes the national figure is far more likely to be higher when including states that do not provide data.

When Tim Curry, the policy and research director at the Fines and Fees Justice Center, looks at D.C.’s automated traffic enforcement system, he sees something familiar.

Curry previously worked at the National Juvenile Defender Center, challenging harmful financial penalties and pushing reforms addressing identity-based disparities. Before that, he practiced defense and supervised third-year clinical law students.

Not because he’s worked in the District for over a decade, but because the patterns mirror what the organization has documented across the country: cities that begin with safety-driven intentions, but quickly grow dependent on revenue from fining their residents.

Curry said this trend motivated FFJC in the first place. After the U.S. Justice Department released its 2015 investigation into the Ferguson, Missouri, police department and found that the city, “budgets for sizeable increases in municipal fines and fees each year” and was exhorting

police and court staff to deliver revenue increases.

One of the most concerning conclusions, Curry said, was that fines and fees had become “a kind of hidden tax,” disproportionately used to extract money from Black and brown residents to fund local governments.

“People in the criminal legal system knew this wasn’t limited to Ferguson,” Curry said. “Our founders decided that no one was taking this on exclusively as an issue and that’s why we created the Fines and Fees Justice Center.”

Today, the FFJC works nationwide to reform fine structures that the community feels are unfair.

In D.C., FFJC’s research and advocacy framework underpinned the local argument in Parham v. District of Columbia, which challenged the city’s Clean Hands Law, once allowing the District to withhold driver’s licenses from anyone owing more than $100 in traffic fines.

One of the facilitators in reforming the Clean Hands Law is Tzedek DC, a nonprofit founded in 2017 with a mission to safeguard the legal rights and financial health of D.C. residents with lower incomes, who often face the devastating consequences of debt collection and credit-related obstacles.

The organization provides free, direct legal and financial counseling services, working in coalition to effect systemic change and offering multilingual community education.

Ariel Levinson-Waldman, founding director of Tzedek DC, emphasizes that their work is deeply rooted in community experiences gathered over years of conversations with residents affected by fines and fees.

“The largest source of fines and fees problems in D.C. has been from parking and traffic-based fines and fees,” said Levinson-Waldman. “D.C. fines our residents more dollars per capita than any city in the country. New York City is number two, left behind by a significant margin.”

Tzedek learned from their community conversations that, under the former Clean Hands Law, residents were not only having their driver’s licenses suspended but also their occupational and small business licenses. Some residents need these licenses to legally work within the District.

These suspensions affected more than 125 occupations, representing over 48,000 workers – including barbers, cosmetologists, nurses, social workers, plumbers, HVAC cleaners, food vendors and more.

In response, they launched a three-part strategy to counter these concerns. One is sharing the testimonies of community members for the public and decision-makers to see. Next, they work with elected officials and policymakers to understand the problem. Lastly, create a sense of urgency for legislative change. They realized that their community’s problems needed to be addressed now, especially in the aftermath of the pandemic.

“We had people who needed to be able to drive lawfully to get medicine, to get food, to get to a job interview, to get to a job. They needed to be able to sell their hot dogs or their pupusas, but they had lost their occupational licenses to do that,” Levinson-Waldman said. “They needed to be able to work.”

He said there were some wins, but more needed to be done. When it came to the issue of driver’s licenses, the legislation seemed to stall, which caused a problem with Tzedek, their partners and their clients.

“We had clients who needed relief right away and we thought that the rule in place was unconstitutional,” he said. “So we brought suit and the federal judge agreed with us, [then] issued an order barring the district immediately from applying the current rule.”

This lawsuit effectively ended elements of the Clean Hands Law. The founding director believes that balancing the city budget to incorporate more money from camera fines isn’t a good strategy.

“We don’t think that’s a healthy plan,” Levinson-Waldman said. “It also creates incentives just to maximize penalties for revenue without any relationship to public safety benefits. There can be public safety benefits to enforcement, but we think it’s important that the District’s financial plan not depend on maximizing traffic camera penalties.”

Tzedek has worked with FFJC, leveraging the organization’s research and educational frameworks to inform their local campaign. Curry explained that while the center focuses on broader policy and research initiatives, including driver’s license suspension reform, local partners like Tzedek handle the on-the-ground advocacy.

“We were partners with them in the driver’s license suspension reform,” Curry said. “Then they took that a step further in trying to get occupational license suspension reforms for court debt as well. They’ve been doing great work in all these things.”

Levinson-Waldman added that Tzedek DC’s coalition has long emphasized that true safety comes from better roadway design, such as clearer signage, speed bumps and eliminating long, highway-like stretches of roadway with high speed limits, rather than relying on escalating penalties.

“Seeing that the legal system is being used both for private mass debt collection as well as public mass debt collection through fines and fees in ways that made the problem worse, not better. Lawyers and people who supported change could play a role in making the system make more sense,” he said.

D.C. is not alone. Cities like San Francisco and New York experienced debt from fees due to traffic camera violations and losing licenses however, with FFJC, those cities have found ways to mitigate harm.

FFJC’s successes

Through campaigns like Free to Drive, End Justice Fees and Counties for Fine and Fee Justice, the organization says it fights to end excessive fines, eliminate unfair collection practices and enforce penalties equitably.

Johnson said one of its most notable victories was its role in eliminating debt-based driver’s license suspensions in San Fransico and New York. They credit their national ‘Free to Drive’ campaign for influencing 50 percent of the U.S. States, including D.C., to regulate debt-based license suspensions.

Before these reforms, millions of Americans lost their driving privileges due to unpaid fines, which made it harder for them to maintain their jobs or access healthcare.

FFJC worked with the state legislature in New York to pass the Driver’s License Suspension Reform Act, which ended the automatic suspension of licenses for unpaid traffic debt. The city now offers drivers’ payment plans tailored to their income. That change restored driving privileges to hundreds of thousands of residents who had lost them for nonpayment.

In San Francisco, the nonprofit worked to launch the Financial Justice Project, which also helped pass legislation to prevent the suspension of driver’s licenses for unpaid tickets. The initiative corresponds with the city’s Office of the Treasurer and Tax Collector. Prompting involvement from community groups and the courts, the objective was to identify which penalties were detrimental to low-income residents, so that more equitable alternatives could be developed.

FFJC believes cities such as San Francisco and New York’s laws caused deep financial harm to Black and low-income communities, along with ticket debt that trapped residents in situations of suspended licenses and court involvement.

San Francisco’s Financial Justice Project found that its lowest-income neighborhoods were disproportionately affected by traffic debt. New York uncovered similar disparities before passing its Driver’s License Suspension Reform Act.

Johnson explained that, as a 7-year-old organization, measuring success is complicated, but they approach it in various ways. FFJC tracks legislation passed, the number of their policies implemented and the spread of awareness around the harm of fines and fees.

She emphasized that the center is developing more precise ways to quantify its impact. They are working to put a number to legislative wins as well as the amount of money saved for individuals affected by policy changes.

“There were close to 300 automated traffic enforcement bills introduced this legislative session, but very few of them passed and became law. We even take that as a success, that the message is getting out. People are understanding the harmfulness of fines and the ineffectiveness of automated traffic enforcement as a solution to improving traffic safety,” Johnson said.

Qualitative interviews with individuals affected by fines are also part of FFJC’s ongoing work to capture the human impact of policy changes. However, these findings have not yet been made public.

“We do policy and advocacy, but really all of this starts on the ground with the people in the community. So, we love to uplift the voices and the stories of people who are directly impacted by these issues,” Johnson said.

From Detection to Citation: The Ticketing Workflow

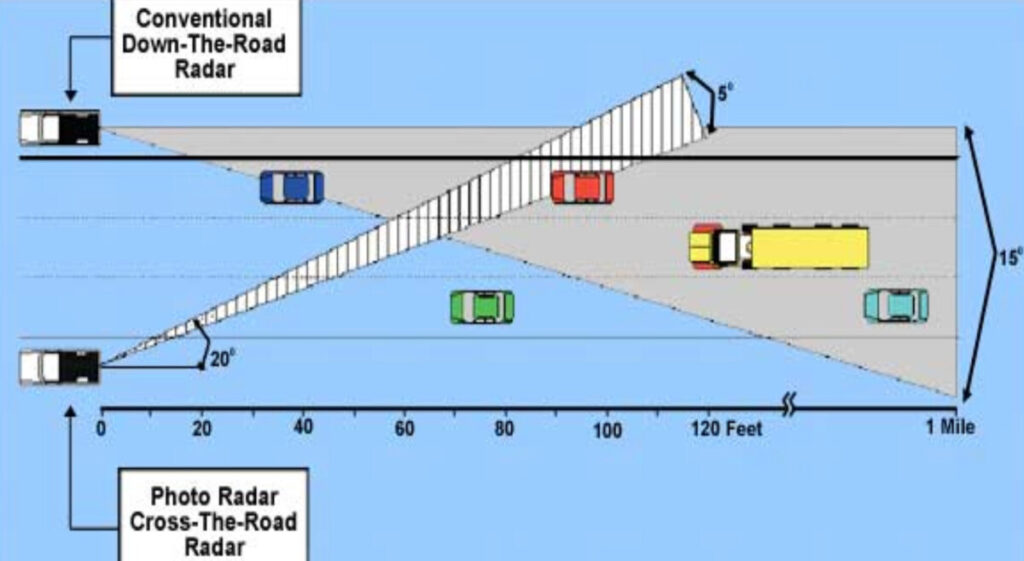

D.C.’s automated traffic enforcement cameras use Doppler radar to clock a vehicle’s speed by measuring the change in frequency as it moves toward or away from the device. Unlike handheld radar—where officers use a wide beam that can pick up multiple cars at once—ATE cameras rely on a narrow beam aimed across the road at close range, typically within 100 feet.

This design reduces the chance of capturing the wrong vehicle. When a car exceeds the speed threshold, the system automatically triggers two photos: one of the vehicle on the roadway and another of the license plate. The camera will not issue a citation if the radar or imaging system malfunctions.

Even though detection is automated, human review is still required. After each deployment, certified technicians check calibration logs, verify the setup, and inspect every image before sending cases to the Metropolitan Police Department. Only after manual confirmation can a ‘Notice of Infraction’ be issued to the vehicle’s registered owner, who then has the same right to contest the ticket as they would after a stop by an officer.

Are Cameras Improving Safety or Filling Budgets?

While the District’s official message emphasizes safety, the financial burden of this story tells a more complicated truth.

In a written statement to HUNewsService.com, DDOT pushed back forcefully against the notion that cameras are positioned to generate revenue or disproportionately ticket Black communities.

“[DDOT] top priority is safety,” German Vigil, DDOT’s public information officer, wrote. “Our automated safety cameras are one of many tools we use to reduce speeds, prevent crashes and save lives.”

He affirms camera placements are based on data findings, such as crash history, speeding, safety concerns and community requests — not revenue or demographics. However, FFJC sees it differently.

“What we know about fines and fees in the criminal legal system and the traffic system is that the outcomes are disproportionately harmful to black and brown communities,” Johnson said. “These automated traffic-enforced cameras are harmful in a number of ways, but particularly for lower-income communities.”

For Miranda Anderson, a resident of Prince George’s County, Maryland, who commutes daily to D.C. for work, the cameras are a constant source of frustration. She says she’s received most of her tickets between Northwest and Southeast D.C.

“I feel that the automatic tickets are unfairly given. And so, because of that, I have challenged a lot of them and won 90% of them,” Anderson said.

She also mentioned that cameras were being used to catch the wrong vehicles and generate revenue for the government.

“When the picture comes, it’s not even my vehicle. It was the other vehicle that was next to me, but somehow it picked up my license plate number. It was actually the other person speeding,” Anderson said.

Anderson believes the government should be more transparent with residents on ticketing policies.

“The D.C. government must be more honest because they are revenue producers. The lack of transparency is why people disregard them,” she said.

She believes the city should reinstate an automated ticket amnesty program to provide relief for residents who have accumulated debt from tickets that doubled after 30 days. The previous amnesty program for outstanding tickets ended in December 2021.

The Ticket Amnesty Amendment Act of 2024, proposed by Councilmember Trayon White Sr., aimed to redefine the city’s “broken” penalty system. In doing so, ticket doubling would end.

While the bill did not pass, further momentum for reform was cultivated. The proposal sparked new conversations around how to build a fairer traffic enforcement system that still keeps streets safe without pushing residents into debt.

“I introduced the original Ticket Amnesty Amendment Act because I’ve seen firsthand how our city’s penalty system pushes too many working-class residents into a financial tailspin,” White said, in a statement to HUNewsService.com. “No other jurisdiction in our region charges people twice for the same offense. Doubling tickets doesn’t make folks pay faster — it simply traps families who are already stretching every dollar to make ends meet.”

This is why Councilmember White said he revived this effort with the ‘Ticket Amnesty Act of 2025.’ The bill would provide residents with a six-month window to pay their original fine for old parking and traffic tickets, with all late penalties waived. The bill was referred to the Committee of Transportation and Environment in October 2025.

“With the cost of living rising and economic uncertainty hitting our neighborhoods hard, this is the right time to offer relief,” he said. “Too many of our residents — especially those who rely on their cars to get to work, take their kids to school, care for aging relatives and hold their households together — are being crushed by a system that issues the third-highest number of tickets in the country and then penalizes them twice for the same mistake.”

He notes that the bill wouldn’t let anyone off the hook but restores fairness to the system.

“This bill is about equity and economic stability. It’s about giving our people a fighting chance instead of punishing them into crisis.”

Last summer, in partnership between Vision Zero, The Lab @ DC, The Lab @ DDOT and the DMV, a pilot program began to lessen fines based on individuals’ incomes. The pilot tested whether lowering fines for low-income drivers would decrease unpaid tickets and collections, which is an issue central to FFJC’s critiques.

Vision Zero Network, a nonprofit committed to ending all traffic fatalities, spearheaded the income-based fine pilot. The organization utilizes FFJC’s reports and data in its campaigns focused on equity in traffic enforcement, specifically promoting speed safety camera programs.

“We’re in conversation all the time,” Curry said. “Cities claim that they’re aligned with Vision Zero’s vision when they’re not. D.C. is an example of that. They always say that they’re following Vision Zero, but they do a lot of things that Vision Zero doesn’t advocate for.”

This initiative followed Mayor Bowser’s creation of a task force to address safety and justice in the ATE system, one of the recommendations being to establish this pilot program, aiming to reduce the cost of fines for individuals who receive food stamp benefits.

However, during the summer, fewer people applied than anticipated, leading them to change their course of action.

“We heard residents might not have learned about the program because they don’t always open envelopes with tickets if they feel they won’t be able to pay them,” said Katie O’Connell, the public information officer of The Lab @ DC.

The Lab pivoted, noting the envelopes to clearly display the discount and added a simple flyer. They expect results in early summer 2026.

Once the pilot is closed, they will measure if recipients got more or fewer future citations following the lottery result.

Anderson said she hopes this program challenges the D.C. government to help the community feel like the tickets are not just a money grab.

“If fines are going to be used as a for financial punishment, they should be proportional. They should be just. That is not what we’re seeing in a lot of communities around the country,” Curry said.

For cities hoping to reduce their dependence on enforcement, Curry said the first step is to be honest about the actual role automated traffic enforcement plays.

“What we try to get cities to do is to look at the goal of the automatic traffic enforcement regime that they have in place. Is it a money-making scheme, or is it really to improve safety? And if it is to improve safety, what are you doing that is actually improving safety?” Curry said. “I think DC is a perfect example of where this really is, in my opinion, racking up revenue.”

Revenue from tickets has become an increasingly important component of the city’s budget. Mayor Muriel Bowser explicitly pointed out that revenue from automated traffic enforcement was designated to balance the fiscal year 2024 budget, with the Chief Financial Officer certifying an expected income of $578 million.

“The city has done some really significant good in traffic redesign,” Curry said. “But if you’ve done the good work on traffic redesign that is going to create the safety change, why do you need to put a camera there too? That’s just to raise money.”

He also notes that the District often highlights individual intersections where crashes have fallen after cameras were installed, but added that those don’t tell the whole story.

“What happens with a traffic ticket is you get some notice of your bad behavior weeks or months later. That has no effect on actually changing your behavior in the moment. But these driver feedback signs do. So if safety is the priority, why don’t we have more of those in the city, in front of every camera?” Curry said.

He believes the underlying issue is the desire for more capital.

“They are addicted to cash. That’s the core problem,” Curry said.

Based on figures from October, a traffic camera in Southwest — northbound toward the city — ranked first in revenue, collecting over $1 million in 2025.

For many D.C residents, the fines are a financial strain that can spiral quickly. According to D.C. Municipal Regulations, speed tickets and photo-enforced violations start at $100 for speeding 11-15 mph over the limit.

The District’s Department of Motor Vehicles says after 30 days, the amount doubles automatically if unpaid. Late penalties can lead to suspended licenses, debt collection, vehicle booting and towing, as well as a possible bench warrant for arrest.

The general discontent towards profit-oriented enforcement and racial disparities is not entirely disregarded. Recognizing these concerns, local lawmakers and advocacy groups are seeking alternatives.

Before Mayor Muriel Bowser submitted budget proposals for the 2024 year, all revenue from traffic camera infractions was reinvested in the Automated Traffic Enforcement fund to ensure improved traffic and pedestrian safety.

Now, Bowser has redirected the revenue from safety funding to an unrestricted general fund, which is used for any range of unexpected events or purposes. The fund does not focus solely on one issue; it provides financial stability, allowing funds to be dispersed across multiple issues.

“We do a lot of research and research does not support the assumption that assessing a fine or even increasing a fine makes someone more likely to be a safer driver,” Johnson said. “People who can pay will pay and just continue to drive however they want. The people who can’t pay are the people who are negatively impacted by those fines.”

City Officials Defend Cameras as Safety Tools, Not a Revenue Engine

DDOT argues that transparency is built into the program. Residents can access a public online map to view every camera in the city and file complaints. New camera requests can be submitted through DDOT or by calling the non-emergency contact, 311.

The agency insists these tools are effective and that traffic deaths in D.C. have decreased by 50% this year, although full crash analyses are still ongoing.

Vigil continued to affirm that once Automated Safety Cameras (ASC) were moved to DDOT in 2019, their priorities were either to prevent a problem or to solve an existing one and that remains true. He said many factors determine whether an automated traffic camera is installed and where it will be located.

DDOT emphasizes that race or socioeconomic status is not involved in the placement of cameras. Some residents feel different.

“It would be great to know why cameras are placed in the areas that they are. Because I don’t feel like I see those types of cameras near Georgetown,” Nicolas said. “I absolutely think they seem to be concentrated in certain parts of the city.”

As many D.C. residents question the motive behind why DDOT places cameras in certain areas, Vigil clarifies the real intention of ASC.

“ASC is expected to change or even prevent poor and illegal driving behaviors,” Vigil wrote. “Decisions on the placement of cameras are not driven by the revenue. DDOT does not have access to this information, as this information is with the Office of the Chief Financial Officer,”

The placements of ASCs are regularly reviewed for effectiveness to ensure that they are improving safety. Additionally, engineering improvements are also consistently assessed.

“Sometimes, ASC may be installed as an immediate safety intervention while engineering improvements are determined and potentially designed and installed to avoid a fatal or serious injury crash,” he said.

Vigil understands that some may not be pleased with the placement of certain cameras. He wrote that if residents want to challenge specific cameras, they can reach out to DDOT’s customer service team.

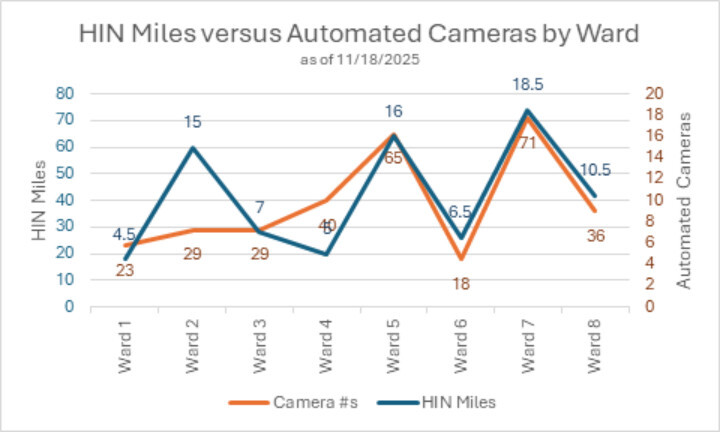

The two wards with the highest High Injury Network (HIN) mileage are Ward 5, with around 16 miles and Ward 7, at around 18.5 miles. HIN is a metric that determines streets with a high number of traffic injuries and fatalities.

The following graph, provided by Vigil, illustrates the HIN mileage by ward compared to the ASCs by ward.

In 2024, the ASC program was further developed by DDOT, and according to Vigil, it led to significant change.

“District-wide before-and-after studies are currently underway for the ASC program, with a focus on a select group of high-violation locations,” he said. “Findings are forthcoming.”

In D.C., advocates are pushing for reform. Organizations such as the Vision Zero Network and Tzedek DC continue to champion and implement initiatives that tackle this issue. FFJC has stepped in to provide reprieve to Black and brown communities.

Nicolas sees the true solution resides between a collaboration of the people, the government and organizations to find middle ground for reform.

“We just need to work together. I’m not saying that we don’t need to enforce because I think it’s important to have some type of regulations. You know, people do speed,” Nicolas said. “I’m not a speeder, but I think that there are other ways to tackle it. It would be great to find solutions to ensure that people are able to actually make these payments.”

Know the Difference: Here are the different types of traffic cameras

According to the Council of the District of Columbia, emergency legislation was passed in 1996, which became a bill in 1997. That bill became the Fiscal Year 1997 Budget Support Act of 1996 (D.C. Act 11-302). This legislation gave the mayor authorization to enable automated traffic enforcement cameras within D.C. The first red light cameras were introduced in 1999, speed cameras in 2002 and stop sign cameras in 2013.

Mobility has long shaped access and opportunity, but Black communities have historically faced restrictions on the road. During Jim Crow, segregation laws limited where Black Americans could travel and subjected them to heightened policing. Even after those laws ended, patterns of disproportionate enforcement persisted, with Black drivers often targeted for stops and fines.

Communities developed strategies to navigate these risks, such as relying on “The Negro Motorist Green Book,” which listed safe businesses and routes. But structural barriers extended beyond individual policing: highway construction frequently cut through Black neighborhoods, displacing residents and creating segregated corridors. These design choices set the stage for patterns of over-surveillance that continue today.

Keith Golden, Jr., Dru Strand, Madison Maynard, Jaiden Thomas and Amani Clark-Bey are reporters for HUNewsService.com