By Chrisleen Herard

Howard University News Service

In 2003, Evan Miller took a baseball bat and beat his neighbor, Cole Cannon, after robbing him with a friend for $300 and some baseball cards. Miller then set fire to Cannon and his home in an attempt to cover up his crime. He was only 14 years old at the time and was sentenced as an adult to mandatory life without parole — nine years later his case would become a landmark for the juvenile justice system.

“Mandatory life without parole for a juvenile precludes consideration of his chronological age and its hallmark features — among them, immaturity, impetuosity, and failure to appreciate risks and consequences,” Justice Elena Kagan stated in the case ruling. “It prevents taking into account the family and home environment that surrounds him — and from which he cannot usually extricate himself — no matter how brutal or dysfunctional.”

The first time Miller attempted suicide was by hanging himself at five years old, when he “should’ve been in kindergarten,” Justice Kagan wrote. This did not come without reason, however, as Miller fell victim to the violent abuse at the hands of his father in addition to the cold grasp of alcohol and drugs, like his parents did.

It wasn’t until Miller was 10 years old that authorities responded to his father’s domestic violence and he was put through the foster system before being brought back to suffer from the neglect of his mother’s drug addiction while increasingly succumbing to his own.

“When you kind of pull back some of the layers, people start to realize there’s a lot of factors that play into why young people may take some of the actions that they do,” said Courtney Ramirez, executive director of special projects for the Division of Youth in Family Justice in New York City’s Administration for Children’s Services.

“The reality is that there’s a very thin line between victim and offender these days, and a lot of the young people who find themselves facing the court with these types of sentences at times in their lives have been victimized. Our system has failed them, and so they’ve kind of taken matters of things into their own hands.”

And yet, Miller’s mental health nor his upbringing were taken into consideration prior to his sentencing. What was taken into account, however, was Alabama’s law that, at the time, mandated life without parole sentencing for juveniles who were convicted of murder.

Mandatory life without parole sentences for juveniles would eventually be overturned when Miller’s case was brought in front of the Supreme Court, so was the death penalty for juveniles in the 2005 Roper v. Simmons case and life sentencing for juveniles who committed non-homicide crimes in the 2010 Graham v. Florida case. The 2021 case of Jones v. Mississippi later reiterated that age may be a factor in sentencing, however it was ultimately left up to the states whether to give a juvenile a harsh sentence.

Though 25 states, along with the District of Columbia, have banned life without parole sentences for juveniles (some with the exception of murder convictions), life sentencing still remains permitted in all states and several hundred inmates continue to serve them.

“I think it’s interesting because a lot of people believe that [Miller v. Alabama] prohibited life without parole for juveniles, and it didn’t actually prohibit it,” Ramirez said.

“You could still have a young person who’s sentenced to life, which is pretty scary.”

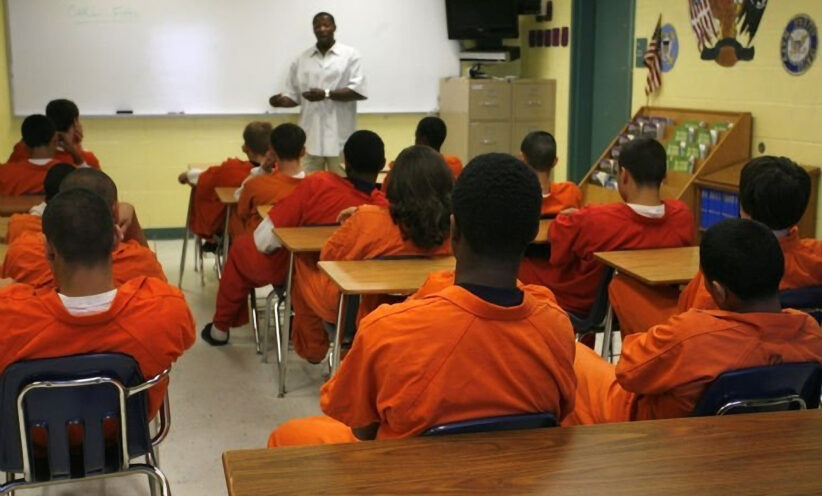

The United States is the only country that continues to sentence juveniles to life without the possibility of parole for a crime they committed before their 18th birthday. Additionally, juveniles who are later sent to centers or prison are not always receiving the support and resources they need in order to walk on a path towards rehabilitation.

Richard Ross, photographer for “Juvenile-In-Justice,” a project that sheds light on the injustice of the United States juvenile system, describes the kind of juveniles he comes across as he uses his camera to capture the stories of the incarcerated youth.

“I ended up photographing at the El Paso juvenile detention center,” Ross said. “There were six kids in a pod, their backs were all facing me, and then I started talking to them and my horrendous Spanish and realized that nobody was listening to them. I was the conduit for their voices and there was nothing else.”

“When they evaluate kids in terms of their background, they look at Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs). So that’s one way of quantifying things. If a kid has a parent or parents that are divorced, that’s one ace. You have a parent that’s a prisoner of addiction, two aces. If they have a parent incarcerated, three aces, and it goes on and on like that.”

“These kids all have multiple aces, so they all have Adverse Childhood Experiences, and rather than having the resources within the community to help them deal with this, they’re incarcerated. And it’s, they’re all tragedies.”

“It’s a system that’s pretty effective at what it does, which is to break children, it’s not really made to help them.”

Besides ACEs playing a partial role in juvenile delinquency, a 2014 study conducted by the Council of State Governments Justice Center found that the juvenile recidivism rate was up to 80% in some states within a three-year release. The center also noted that the “outcomes for youth on community supervision are often not much better.”

But even prior to release, a 2015 study from the National Institute of Justice, which was an update from previous research, showed evidence that there was a continued practice of maltreatment in juvenile correctional facilities, a factor that can explain high recidivism rates.

These practices include sexual and other forms of abuse, isolation, lack of resources to education and mental health treatment and more.

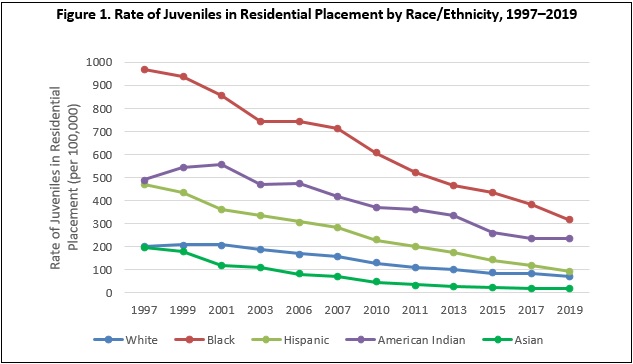

Furthermore, the racial disparities within juvenile convictions reflect those that occur in adult sentencing as well, where Black youth are over four times more likely to be arrested and charged than white juveniles.

“The juvenile justice system in America really, really is reflective of the huge problem that we have around racism and disparity here,” Ramirez said. “And I think it’s glaringly clear when we look in any aspect of the youth justice system in America, but particularly when we look in the deep ends of who’s in facilities and who’s in facilities for the longest terms. They’re almost exclusively Black.”

While the rate of juvenile crimes have steadily been on a decline since they were first reported in 1980, violent juvenile crimes have been on the rise since 2020 while the battle for juvenile justice and reform continues. But what could be done to ensure the rehabilitation of those who are, or have been, incarcerated, and what could be done to prevent future crimes?

“If the person involved is willing to understand the damage done to the community and look for ways that are alternatives to detention, then we will clean the slate for them. And that’s simply one example,” Ross said. “Another example is after school resources. Another example is helping the family and multigenerational situations, helping them escape poverty, and helping them feel like they have something to look forward to rather than continuing a multigenerational line of failure. But it takes political will. It takes societal will. It takes a willingness to say, ‘We can change this.’”

“How do you send a kid to die in prison?”

“The whole idea of the life sentence without parole really is a death sentence in itself. Right?” Ramirez said. “It means you’re never coming back home and [not] being able to even think about having another life.”

“They need to feel loved. They need to feel supported. They need to feel valued. They need to feel like they have the potential to change, to live a life, to grow, to take accountability for their actions and to have an opportunity for something at some point in the future.”

Miller’s case, along with almost 3,000 others, were reviewed after the Supreme Court’s ruling. Over 880 people who were sentenced to life without parole as juveniles were released. Miller was resentenced to life without parole.

Chrisleen Herard covers criminal justice for HUNewsService.com.