By Airielle Lowe

Howard University News Service

For years, fast food has been a highly convenient alternative to cooking at home for the average individual who is too busy to purchase ingredients at a grocery store and then return home to put them together.

Although it’s easier (and in some cases, cheaper) to buy a quick meal, the consequences in the long run can be hazardous. Fast food is commonly known for its high sugar/sodium content and processed meat, but what may not be as obvious are the harmful chemicals found not within the food itself — but in its packaging, according to a new study from Consumer Reports.

This is a widespread problem given that over 36.3% of children and adolescents in the U.S. consumed fast food on a given day, according to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey for 2015-2018. Similarly, data from 2013-2016 revealed that 36.6% of adults consumed fast food on a given day, and fast-food consumption was highest among Black adults in comparison to Asian, white and Hispanic individuals.

A “Forever Home” in Bodies

Consumer Reports — an independent, nonprofit organization with the intent of testing and researching products with the consumer in mind — recently published the results of an investigative study that tested various fast-food products for “forever chemicals,” also known as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS).

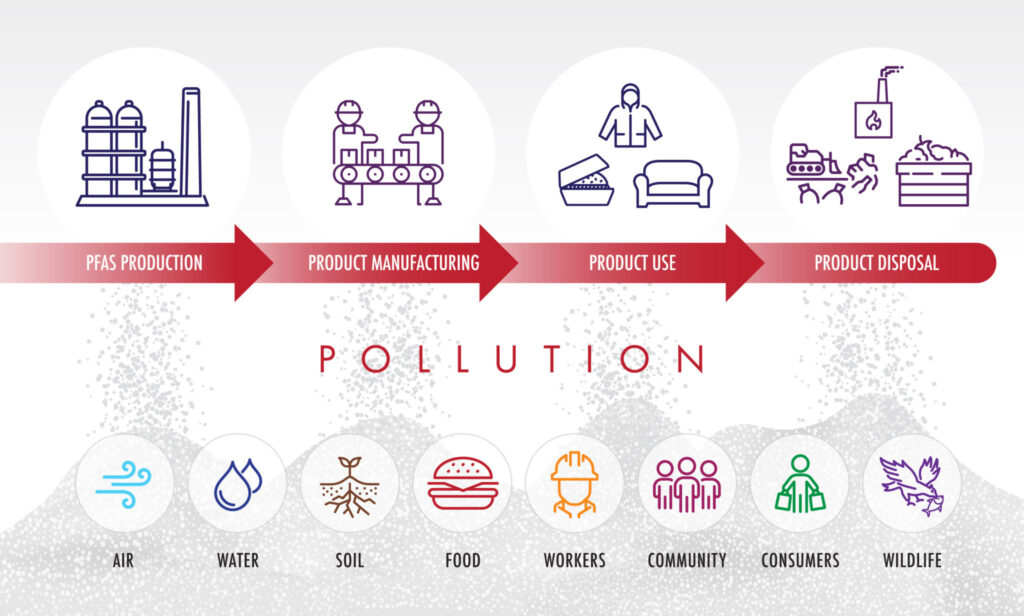

Although there are many different types of PFAS, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) describes them as a group of manufactured chemicals that “break down very slowly and can build up in people, animals and the environment over time.” PFAS can be found in nonstick pans, waterproof gear, certain household products, drinking water and grease-resistant food packaging such as fast-food containers and wrappers, pizza boxes and microwave popcorn bags.

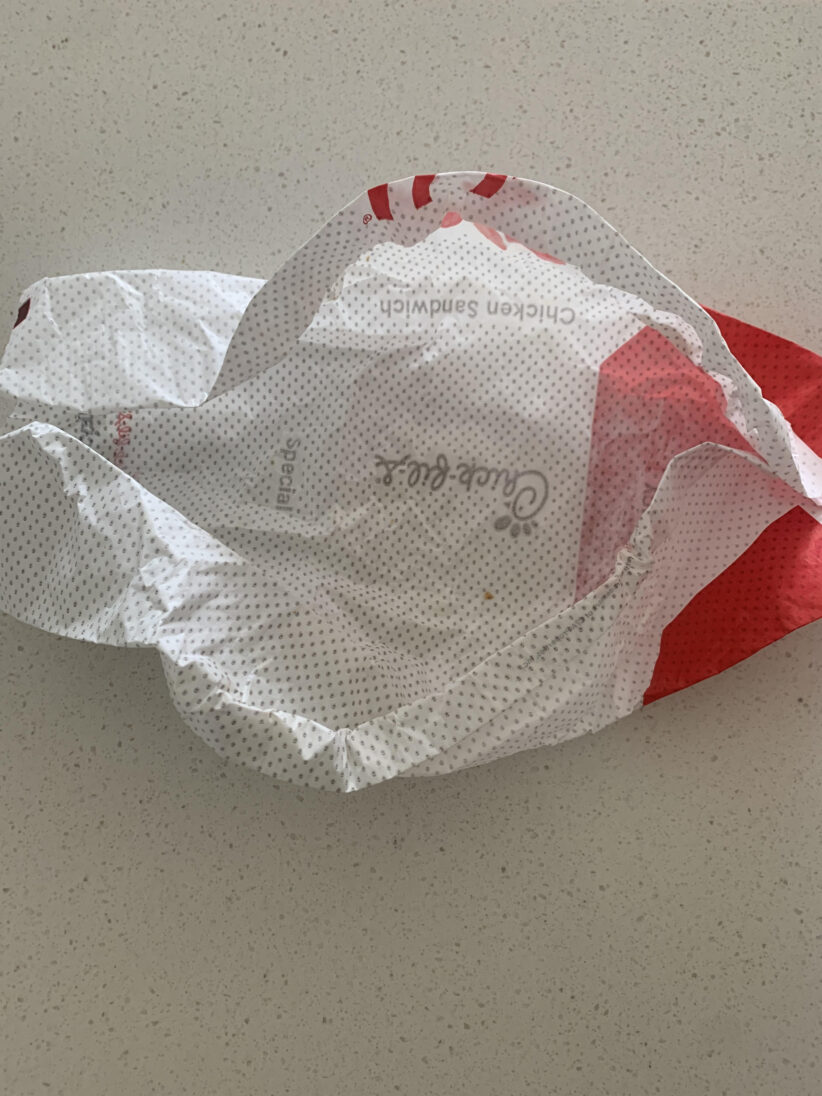

The Consumer Reports study tested numerous samples of 118 products for total organic fluoride content, reportedly contained in all PFAS. More than half of the food packaging contained the chemical, including a Whole Foods soup container, a Chick-Fil-A sandwich wrapper and a McDonald’s french fry paper bag.

“It’s shocking but it leaves me at a loss because I still need to use these things,” said Lydia Jewels, a recent Howard alumna. “It’s not like I don’t want to change the way I do things but how can I?”

As reported by the CDC, exposure to high levels of PFAS can reduce antibody responses to vaccines, increase risk of certain cancers and raise cholesterol levels. High levels of PFAS can also be detrimental to pregnant women, with the potential to cause small decreases in infant birth rates and increase the risk of pre-eclampsia (a pregnancy complication characterized by high blood pressure).

Additionally, the first study of its kind to draw a correlation between pregnant women, PFAS and adverse birth outcomes concluded that in its examination of over 300 pregnant Black women, “higher serum concentrations of PFOA and PFNA were associated with reduced fetal growth.”

In addition to fast-food consumption being highest among Black adults, the CDC report revealed that fast-food consumption was especially higher among younger and middle age adults, and those with higher income levels.

Further, although the overall death rate for African Americans reportedly decreased 25% from 1999 to 2015, African Americans ages 18 to 49 are twice as likely to die from heart disease as white Americans and Black Americans age 35 to 64 are 50% more likely to have high blood pressure.

Considering that Black Americans are more likely to consume fast food and that they are disproportionately affected by health-related diseases and adversities partly due to environmental factors, the presence of these forever chemicals, which may complicate pre-existing health conditions, is especially worrisome. In addition, African Americans are disproportionately located in communities contaminated by companies that make or use PFAS. Disposal of products with PFAS is also a problem.

Solutions? Or Possible Alternatives

Many states have already released legislation looking to ban or limit the use of PFAS in products. California passed a bill in 2021 prohibiting the use of high percentages of PFAS in products, and requiring manufactures of cookware to include a statement on the product label if PFAS were added. The bill will not take effect until January 2023, and some requirements will take effect even later in January 2024. Most recently, Washington state has announced plans to provide more transparency about PFAS usage and regulation, and gradually remove the chemical from everyday items.

However, Principal Toxicologist and Scientific Director at Toxicology Regulatory Services of the SafeBridge Regulatory and Life Sciences Group Craig Llewellyn and his colleague, Olive Ngalame share that PFAS may not be as big of an issue as it may initially seem. “All chemicals have hazards associated with them,” shared Llewellyn. “Hazard times exposure is where you get into risks.”

And according to the FDA, the organization’s testing of the general food supply has noted that “very few samples have detectable PFAS and those that do, have very low levels.” Food testing is still ongoing and monitored closely as well.

“Just because something is in the environment, doesn’t mean it’s going to migrate into all foods,” Llewellyn added. “When the FDA approves an ingredient /chemical to be used in food packaging as a food contact material, they take into account all the exposures.”

Toxicologist Olive Ngalame echoed similar sentiments, responding to the question of whether a person should be concerned about being directly exposed to PFAS as a result of food packaging. “Even though those chemicals are present in the food packaging, it doesn’t mean they migrate into the food.” This is due to the FDA’s food packaging regulation, which monitors the amount of chemicals in food packaging to make sure that this is not the case.

If you’re still feeling uneasy, individuals can take matters into their own hands and limit their contact with PFAS. Although PFAS are ubiquitous and show up in a variety of places outside of food packaging, as suggested by Consumer Reports, knowing what items generally contain PFAS and limiting contact with them can minimize high exposure.

Consumer Reports also suggest limiting fast food consumption or even not reheating your food in its original package. However, these are things that can be more difficult to unlearn and remember to do, especially when traveling with fast food back home or to some other location.

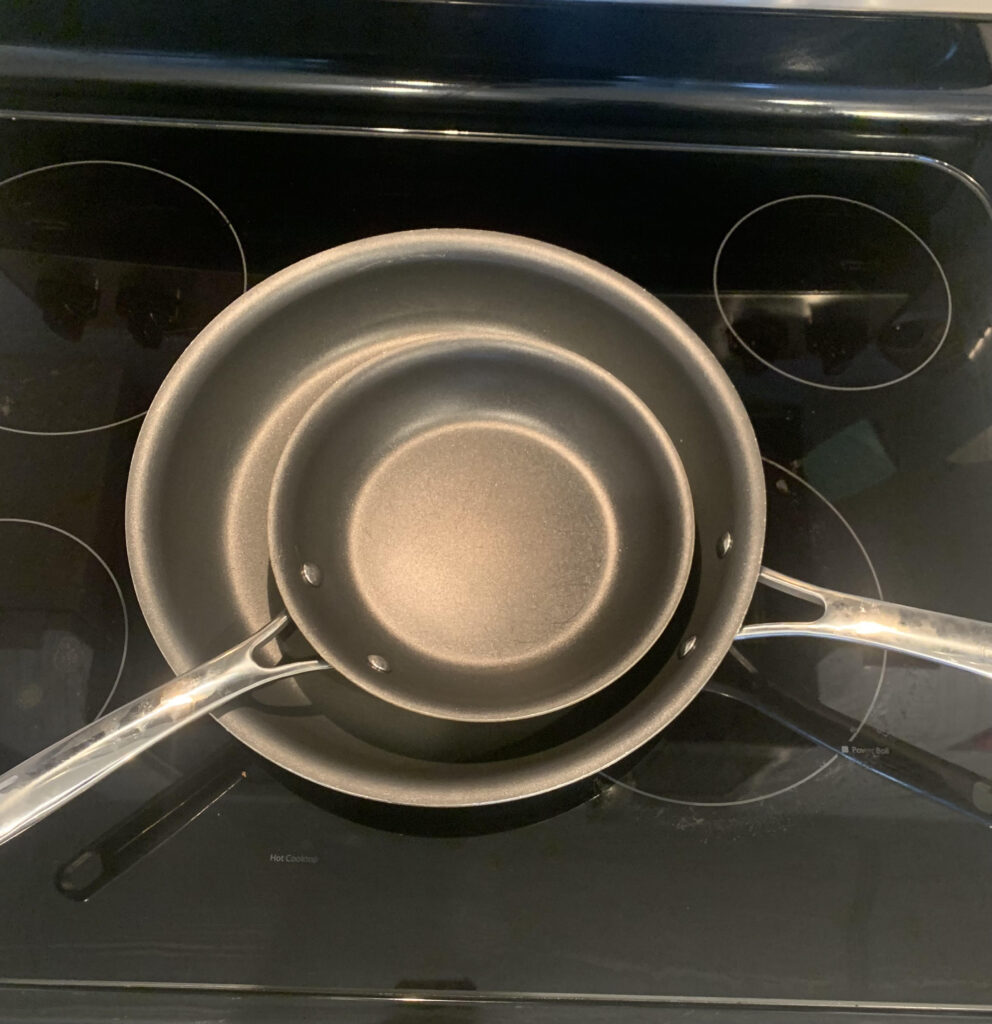

One manageable way to limit PFAS exposure is to switch out nonstick pans. A study from the Ecology Center found that most nonstick cooking pans and some baking pans are coated with PTFE, which creates that nonstick feature convenient for cooking and cleanup. PTFE is typically described as a polymer form of several hazardous PFAS.

Although Ngalame and Llewellyn agreed that nonstick pans are generally safe, Llewellyn cautioned those who may use these appliances incorrectly on a day-to-day basis.

“Using metal utensils to cook with or scraping that coating off,” Llewellyn shared, can increase the risk of exposure. “A chemical is not what is regulated, it is the use of a chemical that is regulated,” shared Llewellyn. If nonstick pans are used in there intended way, the exposure is likely to be minimal.

Nonstick pots and pans coated with PTFE are also known to release hazardous chemicals when overheated, especially to temperatures ranging from 400 to 500 degrees Fahrenheit. Anyone who uses these appliances regularly, are cautioned not to do so with high heat.

Researchers in the Consumer Report and Ecology Center also suggests switching out nonstick pans for stainless steel, copper, glass and cast iron, which are deemed much safer for cooking.

However, Llewellyn also cautioned that certain types of stainless steel appliances can also pose there own unique set of risks.

Ceramic coating is also safer to use and provides similar nonstick properties, though generally has a shorter shelf life. The Green Science Policy Institute, an independent organization that seeks to educate the public about the use of harmful chemicals, also has a list of PFAS-free packaging, clothes and cookware.

Airielle Lowe is a reporter for HUNewsService.com. She also wrote an article about a fertilizer plant explosion in Winston-Salem and other environmental issues in North Carolina for this Breathing While Black project.