Arfie Ghedi Howard University News Service

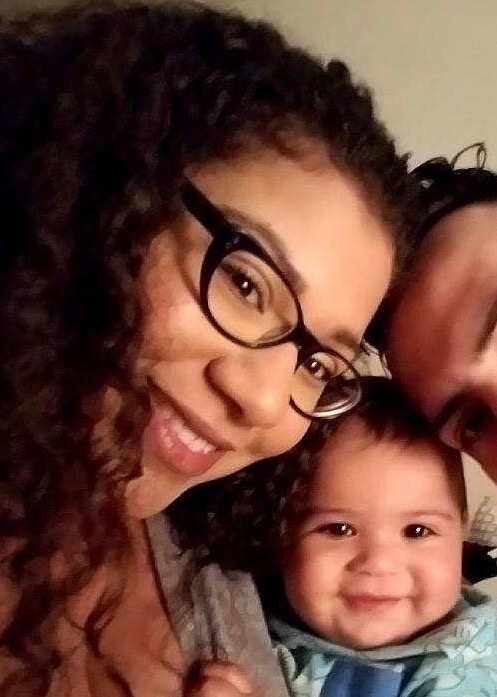

Washington, D.C.– Christena Nataren felt a nervous joy as she returned for her third appointment with her OBGYN at Georgetown Medstar Hospital. It was a combination of emotions she expected, one she’d been saddled with for the past few weeks of her pregnancy with her first child, a son named Thiago. What she didn’t expect, however, was for the doctor she’d been regularly seeing to forget her name.

“I feel like a pregnant woman is pretty memorable,” she said. “It made me realize how big D.C. is, and how many other patients she probably had. It didn’t seem personalized, and that was very scary to me. I didn’t feel safe.”

The 27-year-old had moved to D.C. five years prior from her hometown in Ohio. She worked as a web developer but had two other jobs to cover the high expenses of living in the city. At one of her jobs, waitressing at a restaurant in Woodley Park, she spent her days lifting heavy boxes and running from table to table on the main floor. Her bosses were uncooperative, even docking her pay by relegating her to a hosting position after she’d complained. Nataren’s story—a young woman piled down by stress, both financial and otherwise, having to deal with medical overworked professionals who can’t remember her name let alone the details of her pregnancy—is one that is all too common in the city. It is also a story that very often has a traumatic ending.

Nataren soon moved over to Community of Hope’s Family Health and Birth Center in Northeast, a clinic that primarily serves black women in Wards 7 and 8. “I was about 20 weeks along, I had dealt with so much by then. It was a better experience, a safe haven.”

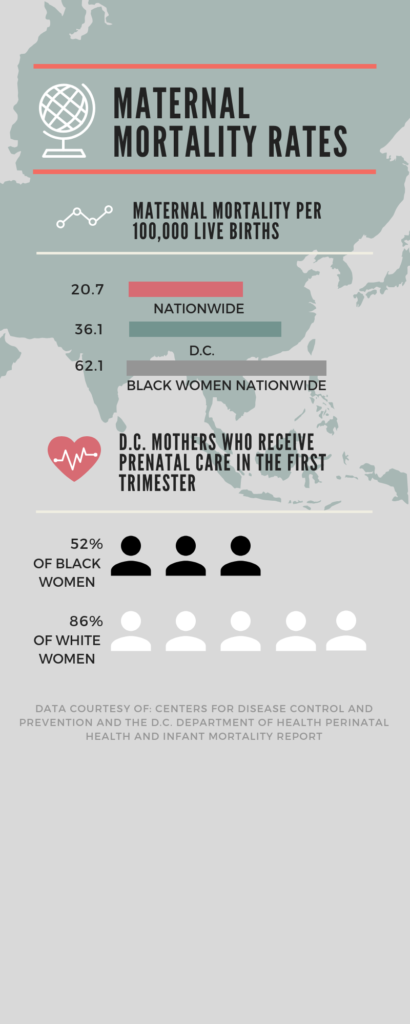

Safe havens in the labyrinth pregnant women face are rare in D.C. In 2017, the city’s rate of maternal mortality, women dying in pregnancy, childbirth, or in the year that follows, is staggering. According to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the rate in D.C. is 36.1 deaths per 100,000 live births while the nationwide average is 20.7. The CDC also finds that black mothers in the U.S. die at three to four times the rate that white mothers do—making black women 243 percent more likely to die from pregnancy or childbirth-related causes.

This disparity in healthcare for black women is the main reason why the maternal mortality rate in the U.S. is one of the worst of all developed countries. Expectant and new black mothers in America die at about the same rate as women in countries like Mexico and Uzbekistan, according to estimates by the World Health Organization.

In October 2017, as most of this data emerged, D.C. also saw the closure of two maternity wards that served predominantly black and low-income women: Providence Hospital in Northeast and United Medical Center in Southeast. Issues such as improper handling of patients were to blame. The ward closures have left many women living east of the Anacostia River without access to care, and have thus stretched other hospitals thin, making experiences with doctors like the one Nataren had at Georgetown Medstar much less pleasant.

D.C.’s maternal health care epidemic is not a new development. According to data from the CDC from 1987 to 1996, the District had a maternal mortality rate of 22.8 deaths per 100,000 live-born infants, once again higher than any other in the country. In April 2018, the DC Department of Health released its Perinatal Health and Infant Mortality Report which showed that black mothers, particularly those living east of the Anacostia River, were at a major disadvantage. Only 52 percent of black mothers received prenatal care in the first trimester compared to 86 percent of white mothers. The city’s response to these figures has been scant, especially when compared to the severity of the issue.

In late 2017, Charles Allen, Ward 6 Councilmember, introduced the Maternal Mortality Review Committee Establishment Act. Its mission was to review all pregnancy-related deaths occurring in the city. However, Dr. Tamari Baker of Community of Hope’s Family Health and Birth Center says that mortality is only a small fragment of the larger issue at hand.

“You could say it’s the tip of the iceberg,” he said. “There’s insurance, stress, hospital segregation, and morbidity.”

Morbidity, as defined by the World Health Organization, is any health conditioned that’s aggravated by pregnancy and childbirth, thus having a negative impact on the mother’s wellbeing. Hospital segregation and drastic differences in healthcare for black people can attribute to morbidity amongst black mothers. Disproportionate rates of chronic illnesses like heart disease and hypertension within black communities have been widely studied. What hasn’t, however, is the idea that health deterioration is a symptom of stress, in the case of black Americans, the stress that comes from racism. “Weathering” is a term coined by Arline Geronimus, a professor at the University of Michigan’s School of Public health, in a study about this idea.

She writes that weathering causes health vulnerabilities and can increase the susceptibility of infection, as well as the early onset of chronic diseases like hypertension and diabetes. Her research also suggests that weathering can accelerate aging at a molecular level. In regards to pregnancy, this means that as women get older, childbirth gets more dangerous and if that happens at 40 for a white woman, it would happen at 30 for a black woman.

“Pregnancy is the most physiologically and emotionally complex time in a woman’s life,” said Carla Henk, Chief Medical Officer at Community of Hope. Weathering has profound and dangerous implications during this time. Stress has been named as one of the most common pregnancy complications and can often lead to preterm birth. In a study funded by the March of Dimes, black women are 49 percent more likely than white women to deliver prematurely.

Christena Nataren’s life is a textbook example of the type of stresses that make black women in D.C. susceptible to pregnancy issues. She’s a professional, a college-graduate, and currently working on another degree in computer science, but the strains of affording a cost of living in D.C. have stretched her thin. She grew up in Youngstown, Ohio, a small Rust Belt city forced into decline with the loss of the major steel industry plants. In the decades that followed, Youngstown became synonymous with crime, both organized and otherwise, and was named by the Morgan Quitno Press as the 9th most dangerous city in the U.S. More recently, however, Youngstown became another casualty in the nationwide opioid epidemic, something Nataren has firsthand experience with.

Even before motherhood, she was already a caretaker. “Before I moved here, I spent my college years taking care of my mom who struggles with addiction, opiates specifically. My father’s currently incarcerated, and he has been for a while,” she said. It was stressors like these that gave her brief bouts of PTSD and anxiety, something she thought she’d overcome by the time she got pregnant.

“I had to be sedated at one point,” she said of her time in labor. “I had a huge, major panic attack and I was out for a few hours. When they woke me up, it was time to push and I barely remember it. I would have liked to have been present for it.” Her panic attack was initiated by the loss of feeling in your lower body that comes with taking an epidural, something that she wasn’t made aware of before being administered it.

When it comes to what Nataren thinks should have been done differently, she shifts the blame onto herself at first, “Next time, I’d do more research,” she said, then, after a moment, “No, actually, I don’t think I could have been more prepared. Next time, I’d hope there are better ways to empower people who get pregnant during that process, better systems of operation, I guess.”

The lack of agency black mothers experience through childbirth is common, and has been the topic of debate due to celebrities like Serena Williams and Beyoncé speaking out about their pregnancy horror stories, particularly citing being ignored by doctors when they voiced their concerns. This, according to Dr. Baker, is also why it’s important to have medical professionals who understand. “There’s not many doctors or hospitals that account for the specific struggles of black women,” he said.

Dr. Baker works at a Community of Hope clinic in Southeast which also predominantly serves black and low-income mothers. “This is an added layer of vulnerability that you have to be aware of especially when it’s a matter of life or death.”

Places like Community of Hope are vital in providing this comfort to black mothers in D.C. Instead of dealing with being rushed in and out of a hospital and doctors who aren’t able to find time to treat them as an individual, advocates exist for pregnant women. “Finding someone you can trust–they just don’t want to let us go,” said Henk, laughing. “It’s a special bond.”

For now, Community of Hope is where Christena Nataren and her son Thiago get their healthcare. “Things get hard, insurance and all of that,” she said. “Mainly, I just want to raise my kid and not feel like I’m being punished for that.”