By Josyana Joshua, Howard University News Service

As the prevalence of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) in Black and Hispanic children becomes more known, experts are urging further understanding of the impact that ACEs can have, especially on minority children.

ACEs are defined by the Center for Disease Control (CDC) as “potentially traumatic events that occur in childhood (0-17 years).” A few examples include: experiencing violence or abuse, having divorced or separated parents, or having a family member diagnosed with mental illness.

Vanessa Sacks, a research scientist at ChildTrends, who co-conducted a study on ACEs, described their prevalence in the United States as a “really critical public health issue.”

“Experiences can trigger what we call toxic stress, which can affect children’s development, and it has been associated in multiple studies with health problems and other problems later in life,” she said.

In May of 1998, the CDC and Kaiser Permanente partnered to conduct a study on the prevalence of Adverse Childhood Experiences. They issued a questionnaire to more than 13,000 adults which included seven categories of ACEs to identify: psychological, physical, or sexual abuse; violence against a mother; or living with household members who were substance abusers, mentally ill, suicidal, or ever imprisoned. This list of ACEs became the one most widely acknowledged throughout the U.S. over the years. More than half of respondents reported being exposed to at least one ACE on the list and one-fourth reported being exposed to more than two. This study also showed that people with six or more ACEs died almost 20 years earlier than those without any ACEs.

Patricia Logan-Greene, a professor of social work and researcher at University at Buffalo, pointed out a few discrepancies with the original study.

“The original set of ACEs were taken as the most common set among a sample of mostly privileged, middle or upper class white patients with health insurance, and this was way before the Affordable Care Act, and a lot fewer people had health insurance than do now,” Logan-Greene said. “That meant that it excluded lots of people with poverty and experiences of discrimination and things like that from being represented in the sample equally.”

Almost twenty years later, in February 2018, ChildTrends conducted a similar study, this time including eight ACEs, not the original categories which did not include some of the more adverse experiences, in their questionnaire based on information from the 2016 National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH).

Despite being a slightly expanded list of ACEs, this list still lacked some of the more toxic experiences, ones that are more likely to trigger a traumatic response.

The ChildTrends study looked at the prevalence of ACEs nationally by state, race and ethnicity. Sacks, noted that the study found, “nearly half of kids in the U.S. have had at least one Adverse Childhood Experience from the eight experiences that we looked at.” The key finding of the report showed that the prevalence of ACEs was highest among black and Hispanic children nationwide.

ChildTrends found the two most common ACEs nationally were economic hardship and the separation or divorce of a parent or guardian. When looking at the most common ACEs across all races, these two experiences stood out. For Black non-hispanic children, the next most prevalent ACE is parental incarceration and for Hispanic children parental incarceration and living with a parent with substance abuse was the next most common. For white children, it was living with an adult with mental illness and living with an adult with a substance use problem.

Both Sacks and Logan-Greene acknowledged the need for more reports, studying and discussing the impact of racism and discrimination on minority children. They also called for the list of ACEs to include more toxic experiences such as abuse and maltreatment.

“I imagine that these numbers that we put out in this report would be even higher if we were also including abuse and neglect and maltreatment,” Sacks pointed out. She noted that these experiences were most likely left off the NSCH, because the people filling the questionnaire were parents. Although the ChildTrend study included some of the more toxic ACEs, like experiencing violence in the community, the original study did not.

As time progresses and more research is made, different experiences are being added and considered as ACEs on the list.

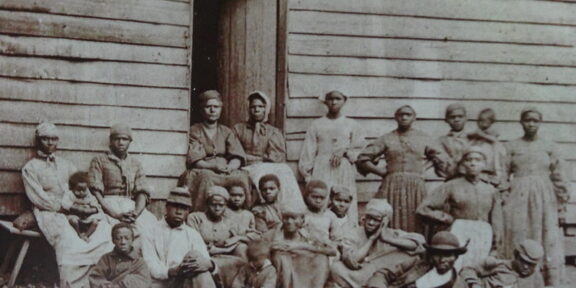

Jeanie Tietjen, director of The Institute for Trauma, Adversity, and Resilience in Higher Education at MassBay Community College said, “Thankfully, if the conversation is beginning to catch up to reality, we’re starting to look at how systemic factors such as racism [and] poverty intersect with issues of ACEs. So the individual sort of adversity. And we’re taking that original ACEs pyramid and adding to it, historical trauma and socio economic inequality.”

ACEs have been connected to numerous issues not only through childhood, but also into adolescence and adulthood.

“We know that when students have their learning disrupted, either for environmental causes, such as being displaced from their homes, or their communities due to political violence or social and economic balance, financial violence, or family disruptions, or immigration or [the] list just goes on and on, went to see interruption in sequential learning, they are way behind when it comes to higher education,” Tietjen said.

She then described the findings of a report conducted by Massachusetts Advocates for Children in response to an increase in expulsion rates in Massachusetts K-12 public schools.

“They found that it was not income level, it was not race or ethnicity, it was not gender or sexual orientation. It was not religious practice. It was trauma,” Tietjen said. “So, the higher the level of trauma, the higher the ACEs scores, the more likely it is that K through 12 was seeing acting out behaviors that had consequential academic adverse impact.”

As an English professor, Tietjen described her students presenting and describing signs of trauma and ACEs when given certain assignments. She gave her classes, 22 students per class, an assignment of a narrative essay, tasking students with describing themselves while connecting it to larger themes.

“And on average, the potentially traumatic events are represented in those student essays somewhere in a proportion of between 18 and 20 per class,” Tietjen recounted. “What was striking was the proportion and also that usually it wasn’t just one adversity being described, it was two or three.” Reading all that her students wrote, provoked Tietjen to open the institute.

It is important to note that like most things that are not good for you, the more ACEs a child experiences, the more negative outcomes a child is likely to face.

According to The Center for Youth Wellness, a pediatric clinic founded by Dr. Nadine Burke Harris to respond to children exposed to early adversity, “experiencing 4 or more ACEs is associated with significantly increased risk for 7 out of 10 leading adult causes of death, including heart disease, stroke, cancer, COPD, diabetes, Alzheimers and suicide.”

The same outcomes people get from smoking, not eating well, not exercising, etc., children are facing the same risk due to circumstances out of their control.

“One of the things that stands out is just how much higher the percentage of children who have two or more Adverse Childhood Experiences is among Black non-Hispanic youth and among Hispanic youth than it is around among white, non-Hispanic and Asian Youth,” Sacks said.

Which in turn means Black and Hispanic children have a higher risk of developing health issues related to ACEs.

The ChildTrend study has garnered a considerable amount of interest since being published in 2018. According to Sacks, people are also doing as much as they can to learn more about ACEs and the impact and effects they have.

“There has been so much momentum on learning more about trauma and how systems and programs and people who interact with children can become trauma informed,” Sacks said.

In addition to raising knowledge, there has also been a drive to develop solutions. Trauma-informed care is one such solution when dealing with ACEs. There are movements to train more trauma-informed teachers, clinicians, and other professions. There has also been an increase in U.S. laws and policies attempting to confront ACEs. ACEsconnection.com, a website where people who want to learn about or inform others on ACEs, includes a map of state laws and resolutions that mention ACEs or trauma.

Despite growing efforts to treat ACEs, children still struggle with accessing treatment for ACEs.

Logan-Greene noted that many children do not get treated at all. “Depending on where you are, you may have access as a child to either excellent evidence based treatment or there may be nothing,” Logan-Greene said. Logan-Greene also mentioned that different areas that may be equipped to help children receive treatment, like schools, usually do not. “Different people have very different expectations of how traumatized children should be treated. A lot of systems, especially schools, are going to have a very punitive approach to children’s behavioral issues.”

Tietjen emphasized the fact that higher education is also lacking in giving students access to treatment for ACEs. “Awareness has not migrated in large part to higher education. It is just beginning to find an articulation in various pockets across the nation,” she said.

How can the impact of ACEs be prevented? The most important thing: the presence of a caring and trusting adult, Sacks said.

“One thing that we know that’s really powerful that can buffer some of the effects of childhood adversity is the presence of consistent and caring adults or having a trusted adult in a child’s life can really help ameliorate some of those later negative effects.” That can be anyone, not only just a parent or guardian. Another is to screen children early on. Families can screen a child on their own with websites like ACEstoohigh.com, which provides ways to help get your ACE score and then take steps to address it after.

“Screening doesn’t happen alone, so that any time you’re introducing screening for adversity, that there is a plan for follow up on whatever that screening turns up,” said Sacks.