When Mississippi issued an evacuation order for its southernmost residents ahead of Hurricane Katrina, Tanya Plummer, 51, wasn’t convinced.

“You know we get rain all the time down here,” said Plummer, a Wiggins resident at the time. “Every week it’s a tornado, a storm or something else.”

“When they said we had to evacuate, I thought it was just another Sunday. Jesus, I was wrong.”

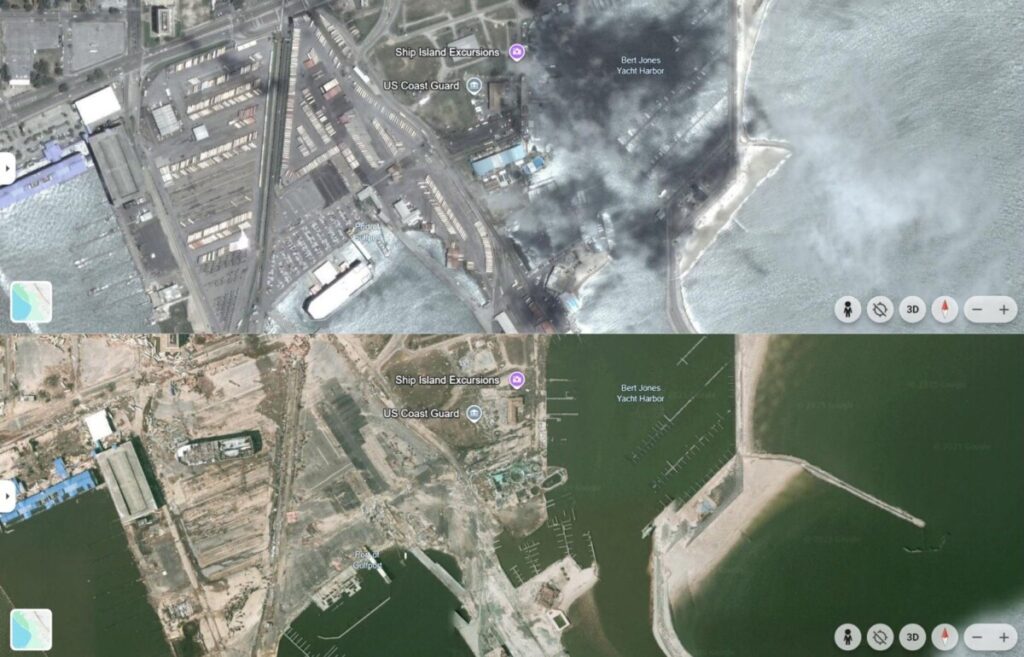

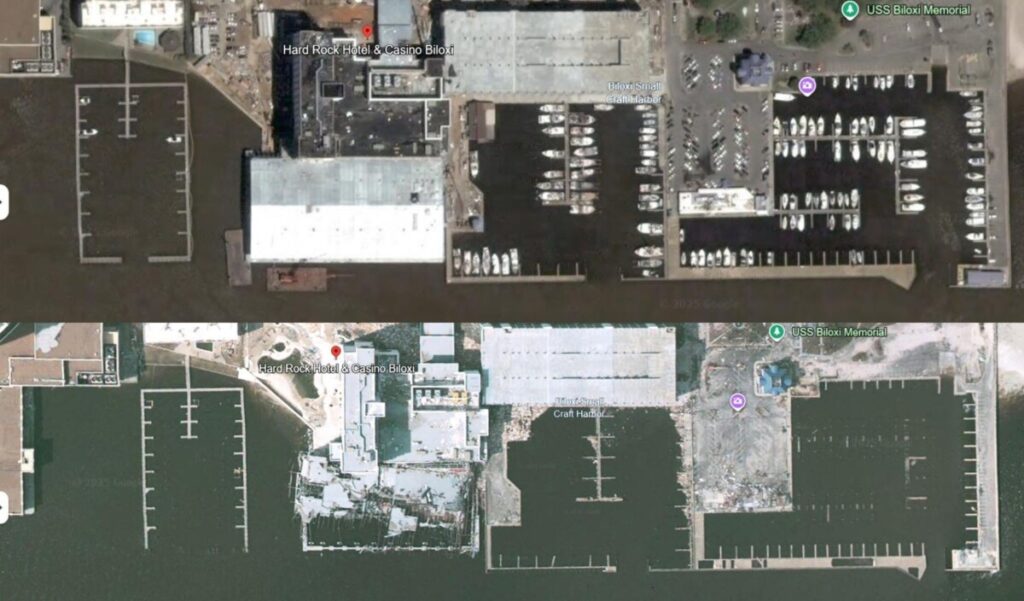

On Aug. 29, 2005, Hurricane Katrina slammed into the Gulf Coast with 125-mph winds and a 28-foot storm surge.

More than 1,000 people died in New Orleans, mostly due to massive flooding caused by levee failures. In Mississippi, 230 deaths were recorded following its encounter with the storm’s strongest section — the eastern eyewall.

Now, 20 years later, Mississippi continues to remember the impact of the storm.

“I still remember that drive, leaving,” Plummer said. “There was so much traffic. I left before the sun went down, and I didn’t make it until late, late that night.”

“I was lucky enough to stay with my family. It was still bad up there though. We didn’t have gas, water, power for over a week. I remember the Red Cross had to be out here to giving out drinking water. Just normal things you take for granted, all gone. It was horrible.”

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, nearly 940,000 people living in southern Mississippi were located within the imminent flood area, and the state recorded the largest land area impacted by Hurricane Katrina.

Gloria Manning, 82, of Ocean Springs, Mississippi, decided not to evacuate.

She remembers looking out of her bedroom window, roofs flying from houses and a large oak tree in her backyard lifting out of the ground.

“All of the homes on the beach, they had looked like a bomb had hit down there,” she said. “All of those big live oaks were uprooted.”

Manning said her community received help, but most of it came from people who traveled in from out of town.

Volunteers from across the country traveled to sites that were devastated by the storm. Among them was Porcia Reaves, 41, from Winston-Salem, North Carolina. Reaves traveled to Mississippi and Louisiana with a relief group during spring break at North Carolina Central University. Students helped residents clean up their ruined homes.

Seven months after the storm, Reaves said the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) was visible. She remembers being in a Biloxi neighborhood on the group’s second or third day when she met an elderly couple, Mr. and Mrs. Burke.

“They had a trailer that was parked in front of what was their home and just remembering just their state of confusion and sadness because they are literally looking at years of what they have built destroyed,” Reaves said.

In the following year after Hurricane Katrina, FEMA provided over 12,000 travel trailers and 9,800 mobile homes to house victims along the Gulf Coast, according to the agency in a case study of the Mississippi Alternative Housing Program.

The Burkes had the bare minimum, Reaves said, including food supplied by rescue missions, a few items of clothing and a couple pictures they managed to save and dry.

The case study reported that residents mentioned improvements to their mental health more frequently after receiving temporary housing than improvements to physical health.

“Living in a unit that ‘feels more like home’ and being able to resume pre‐storm activities, such as inviting family and friends over, created a sense of normality that was greatly valued by program participants,” the case study stated.

Reaves also remembers community members coming out of their homes to grill and feed the group of college students. It was a welcoming experience, she said.

“In Mississippi, I could really see the desire to get people back into the state and back into the city to regrow it or get back to some type of normal life as quickly as possible,” she said.

When she and the group were closer to New Orleans, Reaves said she noticed that it seemed more difficult for the residents there to move towards rebuilding since they were stranded and without help for longer.

“It almost felt like more than what we could assist with versus in Mississippi, I felt like we can at least get some things done.”

She continued that in Mississippi the group was assessing to see what was needed for residents to remain in their homes. For many people in New Orleans, nothing could be kept.

Since Hurricane Katrina, Mississippi has made steady progress in its recovery despite the road being long and costly.

In the immediate aftermath, former Gov. Haley Barbour, who served from 2004 through 2012, created the Commission on Recovery, Rebuilding and Renewal to assess damage and recommend policies to move the state forward. However, the RAND Gulf States Policy Institute reported that while building permits had been issued for 60% of storm-damaged units, the pace of recovery varied. Affordable housing and underinsured properties saw slower progress, and some communities struggled more than others.

Scott Simmons, director of external affairs for the Mississippi Emergency Management Agency, says that since the storm MEMA has taken effective precautions for the future.

“Billions of dollars were marshalled in the state from the federal government to deal with not only storm repair, but also for mitigation,” Simmons said.

Mitigation funds were used for preventative measures to allow the state to be better prepared for future storms.

“Around $500 million was used for mitigation, which helped make systems more storm resilient. That deals with water drainage, sewer systems, storm walls, elevating homes and things like that.”

In Gulfport, all water and sewer systems had to be replaced, including water lines, meters and stormwater infrastructure.

The storm’s impact was not just physical. People living in hurricane-affected areas experienced significantly higher rates of serious and moderate mental illness in the years following Katrina, compared to pre-disaster data, according to a study funded in part by the National Institutes of Health.

Manning, who stayed put in Ocean Springs, said the destruction in her community affected her mentally.

“I was depressed for weeks and weeks and weeks, months,” she said. Water and wind damaged Manning’s home and church. The storm destroyed her roof and led to the demolition of Macedonia Missionary Baptist Church, which was 133 years old at the time.

“It’s almost like you get PTSD from it, because everything was just destroyed. And you couldn’t believe what you were seeing. And then you couldn’t stop going back looking at it.”

Now, in 2025, survivors like Manning said she can see plots of land where homes used to be. Plummer reflects on the storm’s lasting impact.

“Katrina crosses my mind once a month,” she said. “It was such a dark time. It’ll stay with me forever.”

Belaynesh Shiferaw, who grew up in Mississippi, and Damenica Ellis are reporters for HUNewsService.com.