WASHINGTON (HUNS) — The Voting Rights Act now faces its largest threat yet, after more than 50 years as a cornerstone of civil rights law.

On Wednesday, the U.S. Supreme Court reviewed Louisiana v. Callais and Robinson v. Callais, a pair of consolidated cases that could determine whether it’s constitutional to use race to create voting districts — even though the aim of the Voting Rights Act is to ensure fair representation for minorities.

The justices’ decision could significantly reshape how lower courts interpret voting practices. At stake is Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, which “prohibits voting practices or procedures that discriminate on the basis of race, color or membership.” A ruling against Section 2 could narrow its provisions immensely.

In March 2022, Louisiana enacted a new congressional map under House Bill 1, known as HB 1, which included only one majority-Black district. Congressional maps divide states into districts, with each district represented by one member in Congress.

Press Robinson and other plaintiffs sued Louisiana, arguing that the map violated Section 2 by diluting the voting power of Black citizens. Numerically, the map also did not reflect Louisiana’s Black population, which makes up about one-third of the state’s residents. Having only one majority-Black district cuts this population’s power in half.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit, which oversees federal courts in Louisiana, Mississippi and Texas, agreed. In January 2024, the court approved a new map under Louisiana Senate Bill 8 (SB 8), which created a second majority-Black district.

Not long after the bill passed, a group of self-described “non-Black voters” in Louisiana filed a separate lawsuit, representing Callais and arguing that SB 8 was racial gerrymandering. They claimed the map violated the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment, Section 1, by prioritizing race over traditional redistricting principles in the creation of the second majority-Black district.

If the Supreme Court agrees, Callais’ representation calls for a new map to be drawn before the 2026 elections.

But the implications go far beyond Louisiana. A ruling in favor of the plaintiffs representing Callais could weaken Section 2’s power as a tool to challenge discriminatory voting maps.

SB 8 is a solution to be upheld, said Janai Nelson, president and director-counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund and the lead attorney representing Robinson.

“Louisiana’s creation of a district to remedy that discrimination and to ensure that Black Louisianans have an equal opportunity to participate in the process is constitutional,” Nelson argued.

Nelson highlighted that Section 2 is needed because it does not impose a remedy itself but identifies the need for one. This leaves states the flexibility to craft appropriate solutions. She also noted that the application of Section 2 has decreased over time due to effectiveness, not because it is no longer needed.

“Every justice in Louisiana has been elected through a Voting Rights Act opportunity district, and nearly all legislative representatives have been elected on those same districts,” Nelson said. “So, Louisiana alone is an example of how important it is to have Section 2 continue to be enforced to create these opportunities.”

Louisiana’s Solicitor General J. Benjamin Aguiñaga, Kansas City attorney Edward D. Greim and Principal Deputy Solicitor General of the Department of Justice Hashim Mooppan argued against SB 8.

Both Greim and Aguiñaga argued that race-based redistricting under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act is unconstitutional and should be redefined to be permissible only if discrimination is proved intentional. They criticized Robinson’s representation for its reliance on historical discrimination and claimed that the findings were vague.

Justice Elena Kagan said that Section 2 is not about intentional discrimination.

“It’s not intentional discrimination, because Section 2 is not about intentional discrimination,” Kagan explained. “Section 2 is about effects discrimination. It is about Congress saying, and specifically in response to a discrimination of this court, that intentional discrimination and the values behind that prohibition can only be vindicated if under Section 2, the state shows that the effects are not discriminatory.”

Justice Sonia Sotomayor also pointed out to Aguiñaga that the creation of the second majority-Black district was proved warranted on behalf of his state.

“Counsel, with respect, the last time the SG was here before us on behalf of your state, they said that race did not predominate just with your creation of District 6, because what you were trying to do and why it’s oddly shaped was to protect incumbents,” Sotomayor said

Mooppan, who served in the Department of Justice during President Donald Trump’s first term and has since rejoined the administration, proposed modifications to ensure that maps are based on “race-neutral” criteria. He claimed that Section 2 has been misapplied, citing Thornburg v. Gingles, a 1986 U.S. Supreme Court case.

“The problem with Section 2 and Gingles is not that it’s an effects test,” Mooppan said. “The problem with those — with the statute is, as construed in Gingles — it’s reaching far beyond anything that can reasonably present a risk of intentional discrimination as, in fact, making race predominant is requiring states to subordinate their principles to find a result.”

Thornburg v. Gingles is now utilized as a test to determine a Section 2 violation, which also should be modified to promote race-neutrality, according to Mooppan.

Justices Neil M. Gorsuch and Brett M. Kavanaugh both showed intrigue in Mooppan’s solution to redefine Section 2. Kavanaugh called Mooppan’s political objectives “the real innovation” of his briefs.

However, advocates argue that so-called race-neutral approaches fail to address the ongoing challenges faced by minority voters.

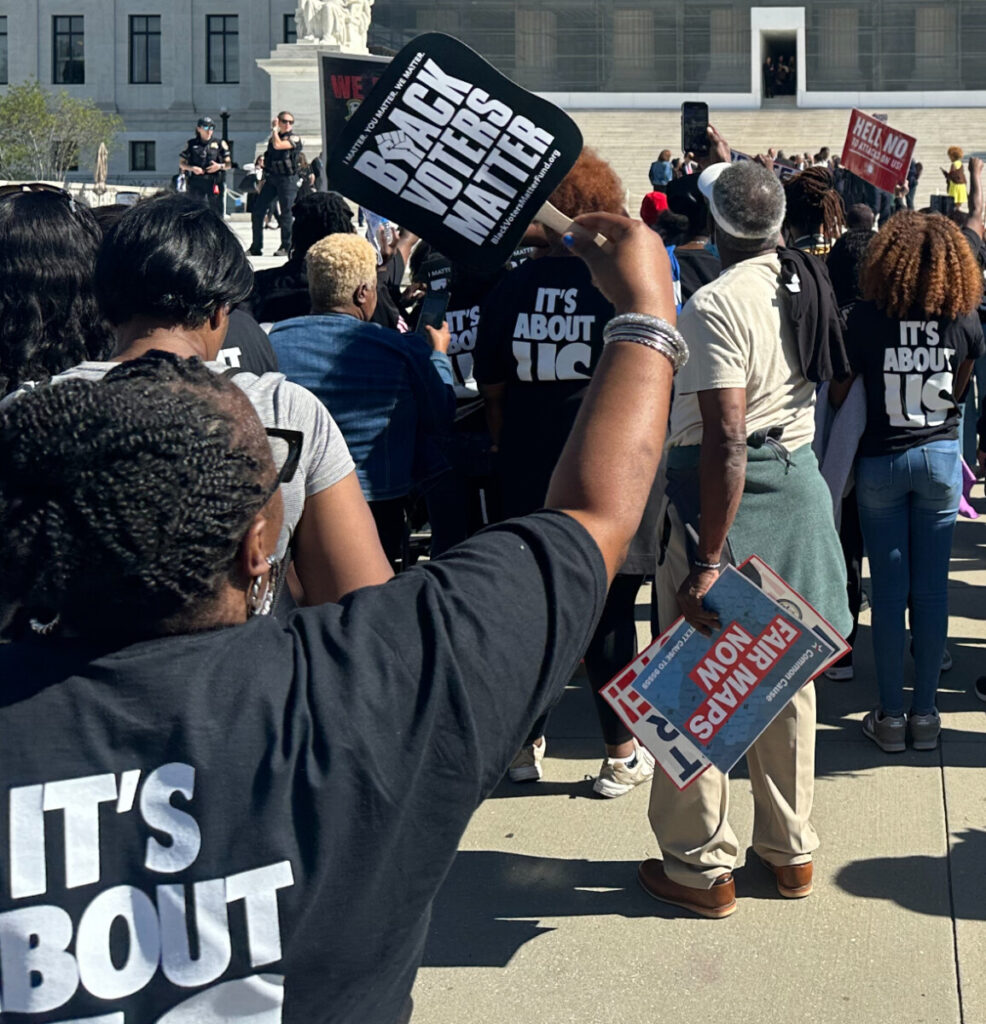

Wanda Mosley, deputy policy director at the Black Voters Matter Fund, says the case is ultimately about fair representation.

“All we want is equal representation. That’s it,” Mosley said, referring to “black, brown and marginalized communities.”

“That’s why we’re here today. We fight voter suppression in whatever form it shows up.”

Diana Brown, a voting advocate from Georgia, aligns the challenges that her grandmother faced to why this moment is so important for her.

“My grandmother is almost 100,” Brown said. “To see what she went through then and what we are going through now are the same. They want to contain our voting rights. It’s very important for us to go back and to educate on this. Let them know we are standing up like we have always done.”

It is uncertain whether the Supreme Court will issue an opinion next summer, along with those in other cases, or sooner. Louisiana has a primary election on April 19, 2026.

As the legal battle continues, Fort Valley State student Carlos Griffin stresses the persistence of the fight.

“We shouldn’t be having this conversation anymore. We’ve been through this already. But, still, every time, we’re going to unite and make our voices heard.”

Belaynesh Shiferaw is a reporter for HUNewsService.com.