WASHINGTON (HUNS) — At just nine years old, the bruises on Taeyana Davis’ body marked the first disruption in her education journey.

Growing up, Davis lied to her principal about how she got bruises on her back — a result of abuse from her mother — out of fear of being separated from her family, even if it meant suffering abuse in her mother’s home.

It wasn’t until her younger sister spoke up that the siblings were taken out of the house and moved to an emergency youth shelter in Columbia, Missouri. This place of refuge came with more abuse and neglect.

As she continued through middle school, Davis was given an Individualized Education Plan (IEP) for her learning disabilities. Soon after being diagnosed with ADHD, ADD, PTSD and bipolar disorder, Davis was placed on medication — but even with medication, stability was something she rarely had.

“I was always far behind. I remember being in a fifth grade class with a third grade reading level,” she said.

Studies show that foster care youth often have lower reading levels than their non-foster care peers. In 2014, foster youth aged 17 to 18 were reading at a seventh-grade level on average.

By the time students like Davis even consider college, they are often further behind their counterparts. The college senior, like many others, did not have established support to hold her hand through the process of applying for and moving into college. Those are the gaps that organizations like Move-In Day Mafia are trying to close.

Move-In Day Mafia (MIDM) is an organization that moves students into dorms at historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs). The program targets students who have aged out of the foster care system.

For many students like Davis who do not receive the opportunity MIDM provides, college is a dream that is difficult to attain.

“If college already isn’t made readily accessible to you, let alone an HBCU, Mafia offers a beautiful pipeline and bridge to that gap.”

Alexis Rodriguez, current Move-In Day Mafia scholar at Howard University

Davis attended Southeastern Community College in Iowa and later transferred to Harris-Stowe State University, an HBCU in St. Louis, Missouri, where she is finishing her last year of undergraduate studies.

When it came time for her move-in process, Davis said she had no support system. She said a friend’s mom, who later came to help her, cried when seeing how alone Davis was.

“I do feel like my experience would have been better if I had Move-In Day Mafia’s help,” she said. “Being in the foster care system takes away the joy a kid is supposed to have and I feel like [their help] would’ve been the first experience of real joy.”

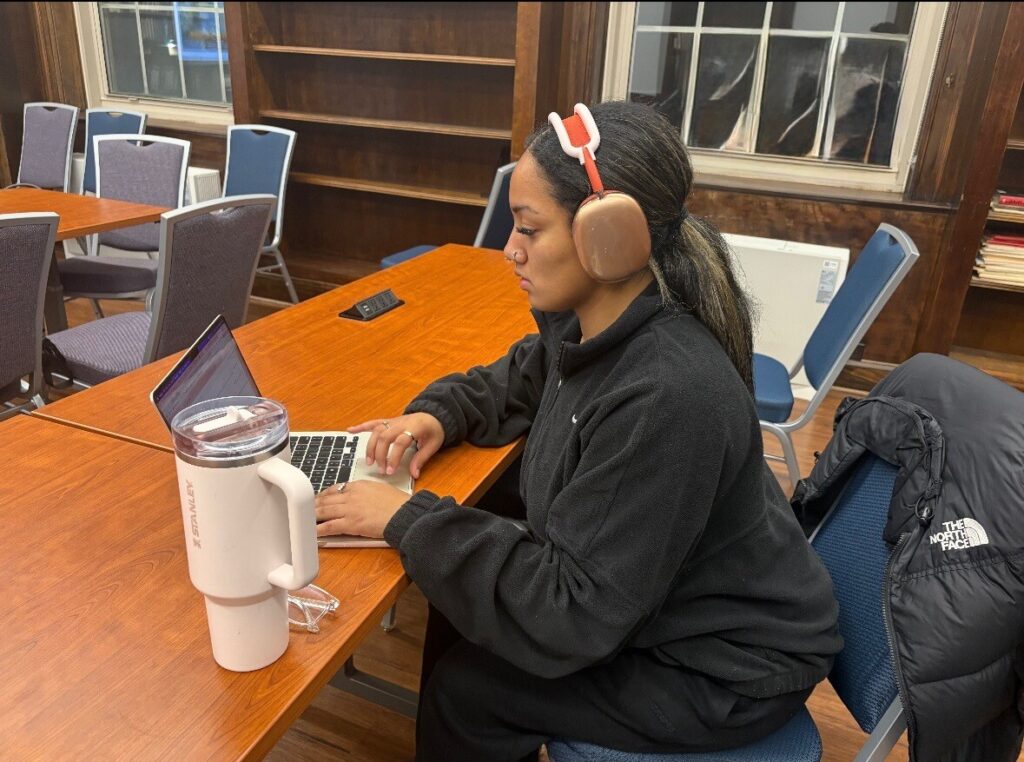

Alexis Rodriguez, a junior at Howard University, an HBCU in Washington, D.C., is a beneficiary of MIDM’s programming. She said with the support of the organization, she is more confident.

“The [MIDM] community I’ve been able to build is what’s helped me been able to stay [at Howard.] …It’s just a great experience knowing that I don’t have to suffer in silence and knowing that there are people who are happy and super excited to help me out,” said Rodriguez.

How did Move-in Day Mafia come to be?

In 2020, TeeJ Mercer found her calling to assist former foster care youth move into college after she met a student who had aged out of the system and had very little support, she said.

Most youth age out of the foster care system from ages 18 to 21 depending on the state they live in.

The student told Mercer that her social worker dropped her off empty-handed at Albany State University in Albany, Georgia, right before the start of the semester. This was the catalyst that inspired her to start the organization — a divine calling, she said.

Mercer, who graduated from Howard in 1994, said she understood that the move-in process is not like that for most students.

“That was not my reality at Howard, that was not my experience and I just knew I needed to do something about it,” Mercer said.

Two years later, Mercer turned to social media to ask for support, wanting to help these students move into their dorms and provide a decorated space designed for them.

In 2022, MIDM was established. Mercer said the organization is learning as it goes, how to best support their students.

Their first year, MIDM worked with Paul Quinn College, an HBCU in Dallas, Texas. There was no application process then. The college handpicked the students who would receive assistance moving in.

Since then, MIDM created an application and interview process where students explain why they need support and provide proof of their dorm assignments.

Mercer knew, after their second year, that the organization could do a lot of good.

“We can be the backbone of students who don’t have family to rely on [or] a support system to rely on,” she said.

MIDM began working with Prairie View Agricultural and Mechanical University to get scholars in the program during the fall 2023 semester before it began working directly with students. Mercer said working directly with colleges is more difficult.

“My focus primarily is to make sure we have money to take care of the students that we’ve promised,” she said. “Reaching out to schools is a whole secondary level.”

A faculty member at the Texas institution’s student affairs office dedicated to kids who are aged out of foster care, asked Mercer if the program had room for one more scholar — a senior who was in foster care her whole life.

“When we interviewed her, I was struck by the fact that she finally was like, ‘Well, I’m a senior and I don’t want to take a spot from a freshman,’” Mercer said. “They will sacrifice for each other and that just makes me want to go harder for them because they are so kind.”

This is one experience, Mercer said, that influenced the opening of the program to all classifications instead of just freshmen. That year, MIDM moved in 31 students at five HBCUs. To date, they now have supported over 100 students across 26 HBCUs.

MIDM now has a 92% retention rate and has seen three of its scholars graduate.

Mercer said her favorite part is watching how each student reacts to someone caring about them — even if it takes nine hours in one day to do so.

“The room is beautiful, but the tears would start when they saw we bought them packs of their favorite maxi pads or packs and stacks of their favorite candy,” she said. “That’s when they were touched and I realized these are things that I take for granted.”

Mafia works with the Nikki Klugh Design Group to design all of their scholars’ dorms. CEO and Principal Designer Nikki Klugh said since the dorm makeover is a surprise, students are treated just like regular clients and fill out an extensive questionnaire so the team can gain an understanding of the students’ likes and dislikes.

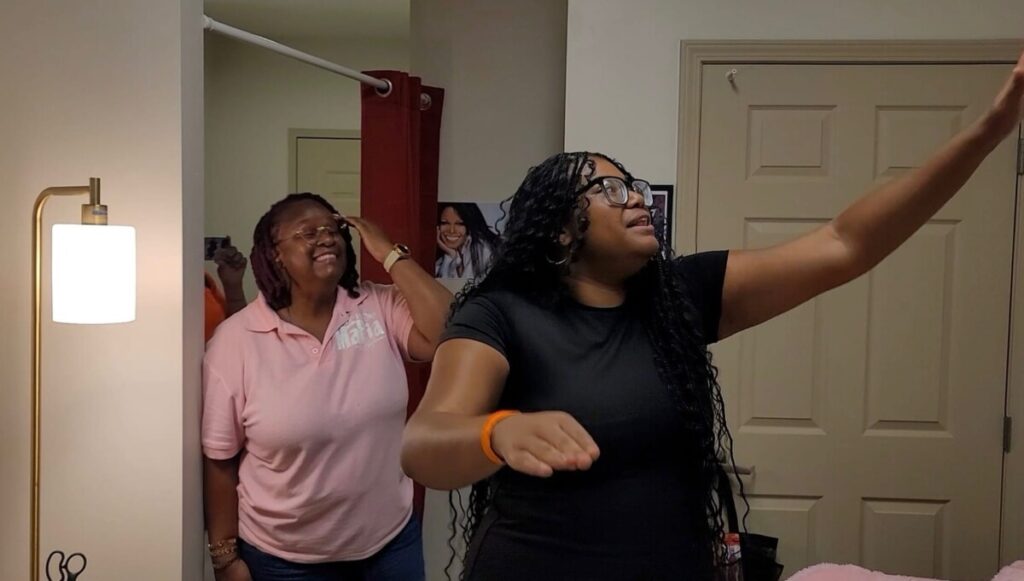

She said during one of the installations, one of the scholars was jumping up and down and repeatedly opening and closing her closet that the team had just installed velvet drapes in front of.

“Just that one little touch really made her day, so it’s just fun to see,” Klugh said.

MIDM volunteers like Stephanie Wilbourn also get to see this impact firsthand.

She decorates dorms and delivers monthly care packages to scholars at Lane College in Jackson, Tennessee. This year, she does monthly deliveries for four students.

“All of their packages actually come to my house. …Once everything comes, I box everything up and I’ll contact the students and let them know when I’m on campus,” Wilbourn said.

Over the years, Wilbourn said, she sees how impactful the deliveries are for the students. For example, one student was able to request a tattoo chair to support her tattoo business.

“When I went to deliver …she hugged me for at least three to five minutes. …I don’t just deliver the stuff…we’re both building a trusting relationship,” said Wilbourn.

Impact on scholars

Rodriguez entered the foster care system as a two-year-old and was placed in kinship care — when youth live with their extended relatives full-time. At 14 years old, she met a mentor figure — her high school history teacher that she now endearingly calls ‘mom.’

“At that point in time, I did not have a lot of trusted adults in my family. I had a lot of overlooked trauma and she was the first human being that I felt was willing to take the extra step to not only activate my potential but show me what forgiveness and grace looks like,” she said.

Although the two had a close relationship, they could not formally complete an adoption while Rodriguez was a minor, since she went to the school that her mentor taught at. Today, they are in the process of finalizing paperwork for an adult adoption.

Rodriguez said she is often met with preconceived notions, including ideas that she is an orphan, was abused, does not know who her parents are and had to grow up around and sleep in strangers’ houses. While this may be true for some, that is not her entire story, she said.

“I know the odds say I shouldn’t make it, but I’m following my own path and it starts with going to school. Sometimes people assume foster kids don’t make it far but I want to change that narrative.”

Adryan Peters, a former foster care youth from Virgina

“There is no singular experience in care. I didn’t have experiences where I was anxious about living with a person I never knew,” Rodriguez said. “I realized I had the ability to take control of my own narrative. If I didn’t want people to associate foster care with all of these things that didn’t relate to my story, I had to speak up about it.”

Rodriguez is Black and Filipino and while in kinship care, she predominantly stayed with her Filipino family members, including aunts, uncles and grandparents. She wanted to attend a HBCU, where the people around her would look like her.

“I felt like all the fingers were pointing in the direction that I needed to be. I applied to Howard early decision. I never even toured the school and when I came to visit after I submitted my [application], it was during homecoming weekend. I felt at home,” said Rodriguez.

During her sophomore year, Rodriguez officially became a Move-In Day Mafia scholar. Her move-in day experience was unique because while the Mafia volunteers were helping move her in, Rodriguez was also helping other students move in as a residential assistant.

“Being able to pour into them while also allowing myself to be poured into, it was just so beautiful because it made me realize how much I’ve grown,” she said. “I always felt like I just had to figure it out and do it myself and so even when I needed help and people would offer sometimes, I wouldn’t want to be a burden.”

Mafia scholars have the option to submit an Amazon wish list every month for basic essentials and self-care items. The wish lists from students are shared with donors so they can purchase the items and then volunteers give the items to students in person.

To address their monthly needs, MIDM has its Amazon wish list that is then posted on social media for donors to buy.

Each student is allotted $200 each month and chooses what they want to put that money towards. Mercer said some people express concerns about what the students are choosing for their monthly care package.

Rodriguez said MIDM is a unique foster care resource because she is able to select the products that she wants. She said for many foster care youths, they are expected to just be grateful to receive anything, but now she can actually pick out specific items, including Black hair care products, without remorse.

“Having that choice without having to be apologetic about it reinforces the humanity,” said Rodriguez.

One of MIDM’s donors that monetarily supports all of their scholars is Lovelace Lee II.

For Lee, the organization’s mission struck a deeply personal chord. Fifty years ago, he attended Hampton University, an HBCU in Hampton, Virginia. Lee calls the university his home in spirit, though his time there ended abruptly after he experienced depression for the first time and did not continue his matriculation.

Decades later, when Lee came across a social media post by Mercer describing the organization’s mission to support foster youth, he was moved to tears.

“By the time I finished reading [her] post, I had tears in my eyes,” Lee said. “Fifty years ago, I met a classmate who moved into his dorm with everything he owned in a pillowcase. When I read about Move-In Day Mafia, it hit me: he was probably one of those students who aged out of foster care and came with nothing.”

Lee, a film and media consultant in Chicago, has no personal connection or experience with foster care; he views his contribution as an act of faith.

“No one should move into a dorm room with their belongings in a pillowcase,” he said. “If it means people who look like us giving so these students can thrive, then that’s what we do.”

Beyond financial backing, Lee said access to basic tools and technology is necessary for student success.

“You can’t do the work if you don’t have the tools,” he said. “It exponentially increases their chances of graduating. We have to help those coming from foster care not just survive but thrive.”

His financial support to the organization, he said, is an extension of his mission to raise awareness and ensure young people never feel as isolated as he once did.

Rodriguez also said MIDM is unique because it supports former foster care youth who go to college out of state.

“A lot of the resources that help kids in care transition to college and the stipends they receive, they don’t extend out of state a lot of times. They’re limited to the county you live in [or] the state you live in,” said Rodriguez.

“Mafia [is] bringing foster youth to HBCUs… [This is] a really beautiful experience because college alone is not accessible unless it’s pushed on you—HBCUs especially,” she said. “If college already isn’t made readily accessible to you, let alone an HBCU, Mafia offers a beautiful pipeline and bridge to that gap that exists.”

HBCUs are known for their long history of graduating Black first-generation and low-income students. These institutions are the top producers of Black professionals in multiple careers, inclduding across STEM-related fields due to their rigorous curriculum and cultural connections.

Although the impact of HBCUs is high across the African diaspora, for former foster care youth, the impact may be harder to come by.

After aging out of the system, many former foster youths seek the support of state-issued tuition and fee waivers to pursue higher education. This greatly limits the accessibility to HBCUs because out of the 21 HBCUs across the country, including D.C. and the U.S. Virgin Islands, less than half are public four-year institutions. Being a public or state-funded school is often one of the criteria a school must meet before being allowed to accept the waivers that some former foster youth have access to.

Impact of the foster care system

As a former foster child, Peter Mutabazi knows well of the challenges in the foster care system. Now, at 51 years old, over 34 children in the past nine years have called him their foster dad.

“To go to college, you don’t begin at the last minute,” he said. “Someone must have helped you in middle school [and] then in high school. So, if you haven’t been helped from the get-go, it’s really hard to overcome that.”

Mutabazi is also an adoptive father to a 21-year-old. With a dream to go to college, no one helped him with reading or to overcome his dyslexia — an eventual barrier to seeing the dream through to fruition.

“He didn’t [get to] go to college because of those big humps [one has] to jump to go. No matter how much you want it, you can barely read. You’re 16, you can barely read, how do you dream that far,” said Mutabazi.

Due to barriers including limited housing, unreliable technology and an overall lack of support to navigate the college system, only 20% of foster youth who aspire to go to college actually enroll.

“Sometimes they will give up on a dream because no one came alongside [to support them] and that’s why it’s important that we don’t wait until they are 16 or 17 to help,” Mutabazi said.

It is important, he said, to have families and agencies who cheer for children in foster care earlier while also not giving up on the older kids.

Adriyan Peters spent his freshman and sophomore year in foster care. Education, he said, became his “anchor.” His experiences in the system shaped his motivation to pursue higher education.

Although Peters said that his upbringing sometimes left him unmotivated to do work or go to class, he said going to college has “always been the plan.” He calls Richmond, Virginia — home.

“I want to get away from this area. There’s a lot of emotions here and I feel like going to school is a fresh start,” he said.

Even though Peters said his education experiences have been troubling so far, he said the college application process was easier than expected.

“It’s been easy, I thought it would be harder … [but] foster care gives you a lot of [monetary] incentives for being in the system. There’s [a voucher] that’s going to help me pay for college,” he said.

The Educational Training and Voucher program is a federal program that provides financial assistance to eligible youth in foster care to help cover the costs of college or vocational training including tuition, books, housing and other educational expenses. In Virginia, the program offers additional state-level support for students pursuing higher education.

Peters applied to Howard University, Norfolk State University, Virginia State University and Hampton University. He plans to major in sociology as a first-generation HBCU student.

“I know the odds say I shouldn’t make it, but I’m following my own path and it starts with going to school,” Peters said. “Sometimes people assume foster kids don’t make it far but I want to change that narrative.”

Once Peters receives an acceptance letter and has a dorm deposit receipt from an HBCU, he will be able to apply to become a MIDM scholar.

Rodriguez also said that her and other former foster care youth that she knows grew up being conditioned to believe that they had to “perform to perfection in order to receive affection.” Over time, she has grown to think differently, she said.

“When I got older, I had to teach myself how to advocate for what I [needed],” said Rodriguez.

For Juliet Alozie, another Mafia scholar, asking for help is not easy, but like Rodriguez, she said she’s learned that reaching out can open the door to the support you need.

“Don’t be afraid to tell your story because there will be people that will be there to help you and that’s what Move-In Day Mafia was for me,” said Alozie.

When Alozie was 13 years old, she and her brother lost their parents in Nigeria, leaving them to move in with family in the United States.

She and her younger brother were adopted by their uncle but what she hoped would be a new beginning soon turned out to be difficult. This resulted in Alozie and her brother being taken in by a family friend which provided the stability they needed.

Growing up going to a predominantly white high school, Alozie said she always knew she wanted a diverse college experience.

“I wanted to attend an HBCU because I wanted to connect with my people,” she said. “It felt like I was missing a part of me and I was missing something in my life.”

When it came time to go to college, she applied and was accepted at Fisk University, an HBCU in Nashville, Tennessee.

Before entering her freshman year, she applied to be a MIDM scholar and was accepted. She said this not only gave her assistance during the move-in process but also a group of people to depend on.

MIDM is a family, she said.

“It has really been a nice experience being a Move-in Day Mafia scholar,” Alozie said. “They have already been there for me throughout my college life. I feel like they are like the people I can really rely on if anything were to go on in my life.”

Struggles with the solution

While MIDM experienced steady growth since its inception, Mercer said after the 2024 move-in season, the program needed to be scaled down. The need surpassed their capacity.

Mercer said if she kept growing the number of scholars at the current pace, some would fall through the cracks. It is too soon, she said, to know how many students they will take in the 2025-2026 school year. Limitations in funding are great.

Getting each student to their respective schools is costly when flights are needed. Because of this, the program started working primarily with HBCUs that were a four-to-five-hour drive away from Atlanta, where the non-profit and Mercer are based. Mercer said she expects to keep it this way until they receive a hotel or airline sponsor.

It costs the organization $5,000 per student per year to cover move-in essentials and monthly care packages. Most of this funding comes from fundraising and corporate partners including Samsung and Best Buy.

Mercer was raised by a single mother. They were not rich, she said, but she received everything she needed. When she came to Washington, D.C. her freshman year, her mother and a family friend drove 12 hours to move Mercer in.

“I had everything I needed and that’s the other thing that always sits with me, because I remember being at Howard and knowing my mama’s payday was on Friday,” Mercer said, adding that she would ask her mother to put money in her account.

Many kids who age out of foster care don’t have that resource.

Mercer said she runs the organization with acute awareness that she does not know what it is like to have an unstable living situation or not have a place to go during breaks.

To try and bridge this gap, she said she ready and surrounds herself with people who are either former foster children or are social workers that work in the system.

“My whole team has the authority to pull my coattail if I’m doing something that could be a trigger,” she said.

On one occasion, Mercer wanted to give students significant attention on their birthdays. It was then brought to her attention that birthdays may dredge up bad memories for some students.

The organization now has a question on a get-to-know-you form that asks the scholars how they like to be celebrated.

Even with support from those with more understanding, there are times when Mercer feels helpless, she said, especially when she does not know what to say during some of the scholar’s hardships.

“I just navigate it with the best that I can [by] leading with my heart,” she said.

MIDM ensures their students have autonomy over their experiences.

“…We only have them for four years,” Mercer said. “They’ve already come out of environments where people are not giving them the top of whatever, they’re always just hand-me-downs. So for four years, I want to give them autonomy.”

By continuing to fundraise, Mercer hopes to increase the program’s monthly budget to include spending money for each student and even add a homecoming committee that can curate swag bags for that time of the semester. A recent corporate sponsorship may cover move-outs in the spring.

“The simple things that we take for granted — I want to fill those holes in the coming years,” she said.

Looking forward, Mercer said HBCUs are doing important work to support students from disadvantaged backgrounds and she wants to help aid that work.

“I’m not going to stop until we have a Mafia chapter on all 101 remaining HBCU campuses,” Mercer said.

The best part? The students know the rooms were created with them in mind.

“I love it when the first thing they do is just grab me and just bury their head in my shoulder, because I knew then that we nailed it,” she said.

David Thomas contributed to this story.

Damenica Ellis, Myla S. Roundy, Tia Pitts and Misha Bernard-Lucien are reporters for HUNewsService.com