<script language=”JavaScript”>var uslide_show_id = “74eb6925-7230-4936-9a9b-a28659071adc”;var slideshowwidth = “350”;var linktext = “”;</script><script language=”JavaScript” src=”/embedslideshow”></script>

The picture of black children playing, the image of black men and women at work, and the smile on Duke Ellington’s face as he sits at a piano are just a few of the photos that capture the black movement that occurred in many northern cities during the 1920s known as the “Harlem Renaissance.”

These are the kinds of images that Addison Scurlock and his sons, Robert and George, sought to capture from their studio in Washington, D.C.

The Scurlock Studio and its photographic work are the subject of an exhibit at the Smithsonian’s Museum of American History, which runs through Feb. 28.

The exhibit is the first of many that the <A href=http://nmaahc.si.edu/>National Museum of African American History and Culture</a> is displaying at the American History Museum before its new home is permanently installed along the National Mall in 2015. As the introduction to the exhibit states, the gallery “focuses on Washington, D.C., through the lens of the Scurlock Studio.”

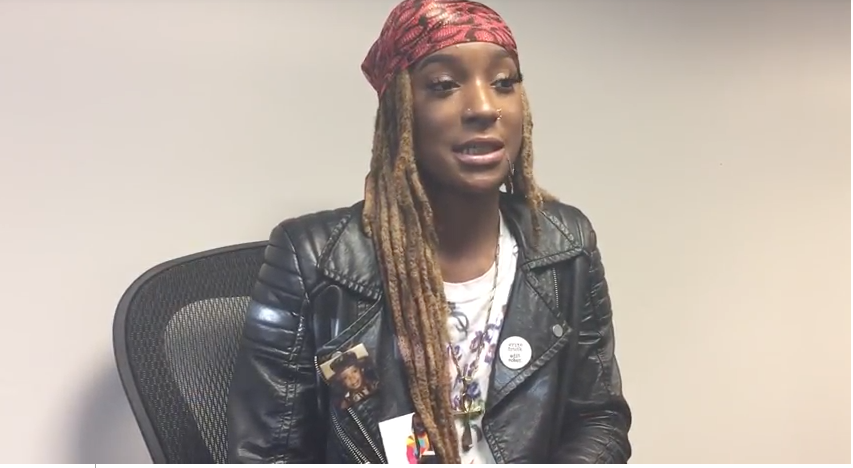

“It is so beautiful to be a part of this,” said Summer Brown, one of the exhibit’s architects. “Hopefully everyone who visits it will get the same look, feel and appreciation for the aesthetics.”

With its dimly lit area and soft music that is featured in the exhibits-only video component, the exhibit provided a contrast from the museum’s other exhibits, which tended to incorporate more patriotic themes and less somber undertones such as the “Americans At War” exhibit or the Abraham Lincoln exhibit.

As visitors experienced the exhibit’s quiet ambiance, whispers could be heard throughout the gallery’s many corners. Visitors praised the Scurlocks’ use of soft focus and described how the soft facial lines in some of the portraits made them just right. Gloria Kirk, a District resident and long-time photographer, was one of the visitors who praised the Scurlocks for the artistic quality of their work.

“It’s a magnificent exhibit,” Kirk said. “I think it has been a long time coming.”

The exhibit takes you through a timeline of events from the year 1900, when Addison Scurlock first moved to the District from North Carolina with his family at age 17. Then, in 1911, when he opened his studio at 900 U St. N.W.

The Scurlock Studio saw black Washington at its very best and, also, during some of its most tense periods.

In 1919, the District erupted in violence as one of many responses to the wave of lynchings and violence toward blacks that was widespread throughout the country at the time. The violence was so bad in some instances that poet James Weldon Johnson labeled it the “Red Summer.”

One of the gallery’s rooms depicts the devastation of the riots of 1968 as white firefighters tried to quell the fire of those buildings that were set ablaze. Like a movie reel, it showcased the events as they unfolded. The caption read that Scurlock took the photos from the safety and vantage point of his studio.

The Scurlocks captured many facets of black life in Washington. They photographed the social, cultural, political and entrepreneurial side of black Washingtonians.

You had the sharp, crisp images of black men in their full military attire and black women socialites looking elegant and regal in their mid-1900s clothing. Some were standing alone, while others were accompanied by their spouses. Many were young, seemingly at the prime of their lives.

Kirk reminisced about her family’s encounter with the Scurlock Studio. “He took pictures of my parents wedding in 1942,” she said. “My father, God bless his soul, is still in possession of those photos.”

“They are truly treasures to me,” she reiterated.

Images of black men and women hard at work were interwoven throughout every grouping of photographs. Most of them were seemingly proud of the work that they were doing, and proud of their culture and heritage.

“It’s good to see black Washington,” said Sara Twyman, an Ohio native and Hampton University alumna. “You always hear of D.C. being Chocolate City, but you never see it.”

“It makes me proud,” said Lygunnah Bean, a Mississippi resident who is visiting the District with the National School Board Association. “It shows young people that back in the 40s and 50s there were positive blacks out there. I’m glad to see the exhibit have a place in the Smithsonian.”

According to the exhibit, after Mordecai Johnson became president of Howard University, the first black to hold that post officially, Scurlock Studios became the premier photographic studio of the university. Scurlock photographed many of the university’s presidents, vice presidents and faculty. These pictures and others can be found on the <A href=http://sirismm.si.edu/siris/top_images/acah.top.05_2007.htm> Smithsonian Institution Research Informations System Web site</a>.

Addison Scurlock retired in 1963, selling the business to his sons. Together, the sons continued to run both Spurlock Studios and Custom Craft Studios, an establishment founded by Robert Scurlock in 1952. Metro construction during the 1970s disrupted the business, ultimately forcing the Scurlock Studio to shut down.

Today, the location that once housed the Scurlock Studio is now a sports bar.

“That greatly disturbs me,” Kirk said. “So much could have been done with it.” She would have rather seen it become a historic landmark or a place to educate others, she said.

“It’s sad that the city has money to do everything else, but can’t use it to preserve history,” Kirk said with a sigh.

For more information about the exhibit and other programs sponsored by the National Museum of African American History and Culture, visit the virtual museum at <A href=http://nmaahc.si.edu/> http://nmaahc.si.edu/</a>.