Gun Violence

All Photos by Alexa Spencer, HUNS: Adia Granger, far right, and scores of Baltimore students came to the march on buses sponsored by Baltimore Mayor Catherine Pugh.. Spencer said her cousing was shot while walking home from work.

WASHINGTON — Adia Granger knows gun violence intimately. The 16-year-old lives in Baltimore, the city with the highest murder rate of any major city in America.

Of the 343 people killed in Baltimore last year, 295 died by gunfire, more than New York City or Los Angeles, cities with more than 10 times Baltimore’s population. Gun-related deaths accounted for 88 percent of the city’s homicides.

Many of the victims were young. Markel Scott, 19, shot six times. Steven Jackson, 18, shot in the head. Shaquan Raymone Trusty, 16, shot multiple times in the upper body. Tyrese Davis, 15, and Jeffrey Quick, 15, shot in same neighborhood within blocks of one another.

Adia’s own cousin was shot while walking home from work. Like her cousin, most all of them victims were black.

Tameka Garner-Barry brought her sons, 2, 5, and 11, to the march to “reclaim”

their schools and their community.

Their deaths were the reason she and a group of classmates from Western High School were among the more than 800,000 who rallied in the nation’s capital to demand more action to deal with gun violence.

“I came here to represent Baltimore,” Adia said.

Adia was among several bus loads of students sent to the march by Baltimore Mayor Catherine Pugh. For them,, gun violence is not new. It is a longstanding issue.

Adia, a high school junior, joined the national movement for gun control sparked by the Parkland shooting by marching out of her school in March, Like many other protestors, she said she wanted the federal government should do more to address the issue.

“It’s unacceptable what is going on,” Adia said, “and Congress has not done anything about it.,”

Adia was many black citizens that were present to protest not only against mass shootings, but also police brutality and gun violence that plagues neighborhoods of color.

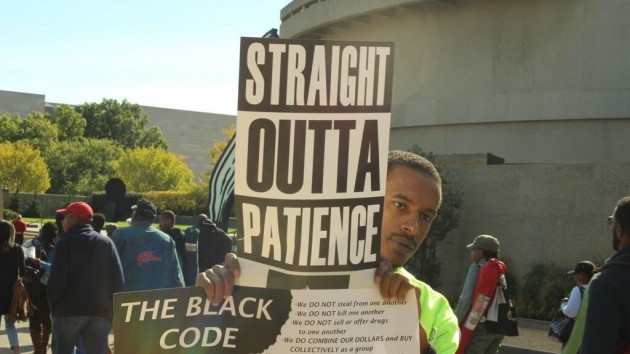

Frederick Shelton, 43, stood aside the packed streets, holding a sign that read: If the opposite of pro is con…what is the opposite of progress?”

The message of his sign, Shelton said is “We’re not moving forward.”

“It’s just a matter of time before any of us get shot, because our federal government is not doing anything,” he said. “We’re all just sitting around waiting for the next mass shooting. It could be you. It could be me. And that’s a horrible way to live.”

Shelton teaches English as a second language to immigrant students in Washington. He said his students are uniquely affected by gun laws and said he participated in the march to make their lives better. He suggested the federal government reserve guns for military personnel only.

“I believe that there is no place for guns in our society,” he said. “Guns are for the military.”

Tameka Garner-Barry, 38-year-old mother of three, brought her sons, 2, 5, and 11, to the march to “reclaim” their schools and their community. Her children, though young, have recognized the problem and wanted to be at the march to speak out.

“These are issues and concerns that they’ve had, so it’s only right that they come out and voice their opinions and let their voices be heard,” Garner-Barry said.

Fred Shelton, who teaches English as a second language to Latino

students in Washington, said guns should be limited to the military.

Standing at his mother’s hip, 5-year-old Bryson chipped in his feelings.

“I feel like people have to stop the violence,” he said, “because people are getting hurt.”

Garner-Barry said she wanted to see the removal of guns from the streets and heightened security in school.

“I want Congress to know that we do control the vote, and that we take these issues seriously,” she said, “and I want the NRA to be dismissed altogether,”

Nia Smith, 21, a graduating senior film production major at Howard University from Chicago, was also at the march.

Chicago had the highest number of murders two years in a row. In 2016, 771 were killed. The number declined to 650 murdered in 2017, still higher than the number of murders in Los Angeles and New York City combined.

“Gun violence has always been a part of my life,” Smith said. “I have had family members that I’ve lost to gun violence.”

Though the march addressed gun violence, including some speakers who tlked abut gun violence against African-American men and women, she said she felt as though certain forms of gun violence, such as police brutality, were overlooked by protesters because of class and race.

“They fail to see that gun violence is gun violence, period…the police and the perpetrators of the classroom shootings,” Smith said.

To fully combat the issue, there must be support across racial lines, she said.

“I don’t think they should be separated,” she said. “I think white people should march the way they marched today for the Black Lives Matter movement. They all died the same way. They all died by a bullet.”