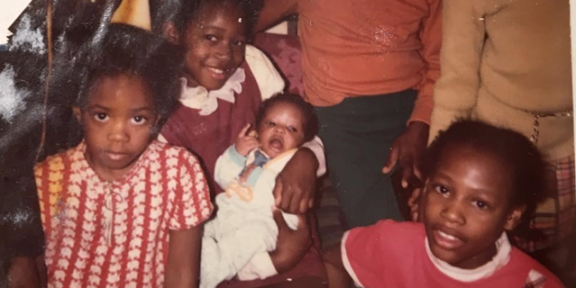

Brenda Carpenter gazed out the living room window of her white two-family home in Southeast D.C., painfully describing how drugs and HIV/AIDS have inflicted challenges on her family. At 73, Carpenter is raising 13-year-old granddaughter Shanntanee and 10-year-old grandson Lamont.

Carpenter left home and began using dope at the age of 9. Her hands are swollen from the side effects of the medication she is taking, since she is HIV positive.

“When I first found out I was diagnosed with HIV, I was in jail locked up for writing illegal prescriptions and taking them to the pharmacy,” she said. “I called my mother and told her I was going to die.”

Carpenter’s oldest son died from AIDS at the age of 29 in 1993. Her eldest child and only daughter died at the age of 45 in 2002 from an overdose of cocaine.

Kenneth, 42, and Mike, 32, are the only children she has alive. But, Mike is serving life in prison without parole for murder, and Kenneth has been in a rehabilitation center for alcohol addiction.

Carpenter believes Mike is innocent. “He’s too young to be locked up for that long,” the heart-stricken mother said. “I pray for God to bring him home everyday. I don’t know, but He’s the only one that can turn all that around.”

Mike is the father of Shanntanee and Lamont. The children’s mother has full-blown AIDS and is in care at a nursing home.

Carpenter has been clean now for 12 years and has been taking care of both children since 1999. She received full legal custody of Shanntanee in 2003 and has had joint custody of Lamont with the children’s mother since 2005.

It hasn’t been easy raising them, especially Shanntanee.

“We don’t talk,” Carpenter said. “We don’t laugh no more. Her brother don’t want her to come home, because he knows it makes me sad. But I still pray and I ask the Lord to keep her safe.”

Shanntanee’s behavior has become uncontrollable. She comes home at all hours of the night and doesn’t want to do chores. Carpenter worries whether she is attending school everyday and doing her homework.

“When Shanntanee was younger, she was smart.” Carpentar says trouble began when Shanntanee began stealing money from her at a younger age and sending threatening emails to a classmate.

“I warn her of the crazy world out there,” Carpenter said weeping. “I know, because I’ve been there before.”

According to the U.S. Census Bureau as of 2007, Carpenter is one of the 8,183 grandparents in Washington who are raising their grandchildren; 90 percent are African-American. Her grandchildren are among the 16,723 children in D.C. who are living in grandparent-headed households.

According to a 2007 report by the Kaiser Family Foundation, Carpenter is also part of the estimated 1,881 adults living with HIV in Washington, one of the hardest-hit cities in the nation.

Balinda Cunningham, 58, who is also HIV-positive, has been raising her 9-year-old granddaughter, Tierra, since she was a baby. Cunningham’s 29-year-old daughter, whom she would not name for privacy reasons, is unemployed and homeless.

“I have a court case coming up against my daughter for full custody of Tierra,” Cunningham said. “My daughter had family members coming to court in the past saying that I just wanted to use my granddaughter for money. This has broken my family apart.”

Cunningham has guardianship of her granddaughter, and they live comfortably in a Fairfax Village apartment in Southeast D.C. She said things are going pretty well for them now, but things weren’t always this way.

“We got evicted from our old apartment because my daughter didn’t want to help pay the rent. So my granddaughter and I had to move into a shelter. There were mice crawling everywhere. One crawled on my granddaughter while she was sleeping, and they wouldn’t do anything about it.”

Eventually Cunningham was able to move to her current residence with the help of the Shelter Plus Care Program, which is run by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

While she was living at the shelter in 2007, she met Michelle Parmer, a director at the time of the Family Ties Project in Ward 5.

Sally Altland, project director at Family Ties, says the organization’s main focus is assistance in life planning for families affected by HIV/AIDS. “We provide counseling, help with obtaining housing, budgeting skills, as well as support groups.”

The support group, which meets twice a month, includes about eight to 10 older women who have families. Family Ties also provides youth empowerment and partners with Pediatric AIDS/HIV Care Inc. to work with infected children.

“Family Ties helped me with legal issues, food vouchers, transportation and also helped my granddaughter Tierra with medical assistance,” Cunningham said.

Carpenter has also been part of Family Ties since 2003. She and Cunningham have both advocated on Capitol Hill with Family Ties for the Grandparents Caregivers Pilot Program directed by the D.C. Child and Family Services Agency. It provides older people who are raising grandchildren, great grandchildren, grandnieces and grandnephews with money to help take care of them.

Carpenter passionately advocates and speaks out about her life story. “I’ve done presentations at George Washington University and other colleges. I also educate older individuals about HIV/AIDS. It’s my way of helping someone else.”

As an artist, Cunningham is part of the Ward 7 Arts Collaborative and helps teach teens about the harms of substance abuse. She received an award from Councilman Tommy Wells of Ward 6 for Outstanding Community Service.

“I don’t get paid for this, but God blesses me a lot.”

She is also battling cervical cancer. However, Cunningham has hope for the future. “God is good because my cancer is in remission, and my HIV is undetected.”

Her granddaughter, Tierra, has been the perfect companion.

“She said since I took care of her when she was a baby, she’s going to take care of me now,” Cunningham said. “She washes the dishes, helps me remember to take my medication and does the laundry. I thank God for her.”

Carpenter has also found comfort in her many pets including a cat, dog and snake. Her grandson, Lamont, is also a spring of hope. Carpenter said her grandson was just removed from special education last year and is now in regular classes. When she got him, he was 9 months old. She later noticed that he had speech difficulties as a young child.

“Grandma, I finished all my homework; may I please go outside?” Lamont asked charmingly. He wants to go to his friend’s football practice nearby.

“You better be back to come with me to my meeting,” Carpenter replied. “Yes Grandma,” he said obediently with a smile.

“I tell Lamont all the time to have respect and manners,” Cunningham said, “because that’s what’s going to get you far in this life.”