Black History Month: Eugene M. Deloatch:

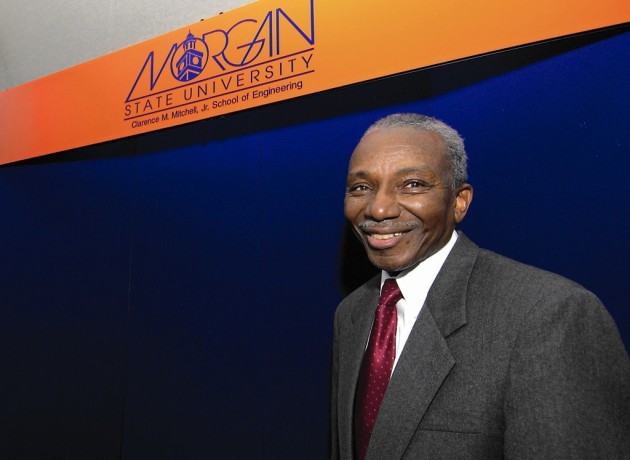

Courtesy Photo: Eugene Deloatch, founding dean and dean emeritus of the Morgan State University Clarence Mitchell School of Engineering, was named Black Engineer of the Year recently for his work training more African-American engineers, more than 2,300, than anyone on earth.

WASHINGTON — Most people have never heard of Eugene M. DeLoatch, but all over the world, they have seen the fruits of his labor, across the United States, in Puerto Rico, the Middle East, Japan, Germany, Korea — across Europe, Africa and South America.

The people he trained have built buildings and other structures, molded rivers, solved problems and created solutions that provided relief and sustenance to millions of people in virtually every part of the globe, from Alaska to Zaire.

DeLoatch is the founding dean and dean emeritus of the Morgan State University Clarence Mitchell School of Engineering, creating the Baltimore school in 1984 at a time when few believed it was possible to train so many black engineers.

Additionally, he has trained more African-American engineers than any person on the planet. Those students, more than 2,300 by last count, have helped reshape the world.

Amidst numerous challenges, in the face of skeptics and with limited funding to historically black colleges and universities, DeLoatch led the Morgan State University engineering program to success.

Former President Obama acknowledged his work in a personal letter, calling DeLoatch the “best of the best” in the field of engineering. Just last week, he was named the 2017 Black Engineer of the Year during a ceremony in the nation’s capital, a title awarded after his more than 30 years dedicated to the betterment of black engineers.

DeLoatch said when he took on the task of creating the school, he saw challenges, but he also saw an exciting opportunity.

“When you’re able to start the school and hire the people and set the programs… it’s a fun challenge,” he said.

His personal journey into engineering was almost accidental, he said.

When he was a sophomore in high school, his French teacher saw a magazine that talked about the deficit of African-American engineers, he said. The magazine said engineering could be a new opportunity for “the negro.” The teacher asked the young DeLoatch if he had ever considered becoming an engineer.

“That question stuck with me,” he said, “I didn’t know why she would ask that. Engineer wasn’t in my vocabulary at that time.”

DeLoatch grew up in a small, mill town in New York called Piermont. He attended Tougaloo College, a historically black college 10 miles north of Jackson, Mississippi. DeLoatch earned dual degrees in mathematics and electrical engineering from Tougaloo and Lafayette College in Pennsylvania.

It was during college that DeLoatch said he experienced raw segregation for the first time.

“In Mississippi is where I got introduced to signs that said colored only and riding in the back of the bus,” he said.

After earning his engineering degree, he became an engineering instructor at Howard University, a historically black college in Washington.

He stayed with the university on and off from 1960 to 1984 while earning a master’s and doctorate degree. DeLoatch spent his last nine years at the university as the chair of the Department of Electrical Engineering.

In 1984, DeLoatch he began the Morgan State University engineering program. One of his first challenges was that the building set to house the engineering program did not have classrooms. The state of Maryland determined that Morgan’s campus already had enough classroom space.

Additionally, many people questioned whether black students who could handle a rigorous engineering program. DeLoatch decided to ensure that his students would be prepared for the program by creating a summer transition program. Almost from the start, Deloatch disproved his skeptics.

In just seven years from its start, the program had awarded 76 percent more engineering degrees to black people than the entire sate of Maryland did just a decade before. More than 40 percent of the bachelor’s degrees in engineering awarded to all black students nationwide were earned at the university.

Deloatch said he credits the program’s success to the young people who enrolled and later graduated.

He can point to graduates like civil engineer Dale Ann-Marie Duncan, civil engineer Adrian Devillasee and electrical engineer Delray Wylie. The three, all members of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, volunteered to go to Afghanistan to help rebuild the struggling country following the U.S. invasion and the protracted fighting that destroyed many of its cities.

Meanwhile, Keysha Cutts-Washington is a project manager with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in the European Division. And there are thousands more.

“The young people who’ve come to study, they are the success,” he said. “To see them come in and go do tremendous thing is what gives me the greatest joy.”

DeLoatch began to be recognized for his work in 2002 when he became president of the American Society of Engineering Education, making him the first African-American to hold that position.

DeLoatch encourages young people to reach for their dreams, no matter the odds.

“You have the talent within you," he said, "If you are willing to spend the time and money, you can do practically anything that is possible.”