By Danielle HanksHoward University News Service

As history is being made with Barack Obama becoming the first black man to be president of the United States, I not only reflect on what this means for all citizens, but also on what it means to me.

Like Obama, I am biracial. My mother is white with an Irish/Norwegian background, and my father is African American. So what does that make me? Until now, I wasn’t sure. Although I had a great childhood growing up with my mother and grandparents on a farm with cattle and horses in the predominately white community in Puyallup, Wash., there was always something missing.

I wondered why no one else looked like me. I wondered why my mother couldn’t comb my hair without me crying while the comb seemed to just slide through the locks of my friends. I wondered why teachers in junior high school would come to me and ask if I would be comfortable reading the required text for class that dealt with racial issues, or if putting certain pictures up around the class would offend me.

I did not quite understand why I was always being singled out.

In hindsight, my situation seems parallel somewhat to Obama’s youth experience. In his 1995 memoir, “Dreams from My Father,” Obama mentioned struggling with his biracial background. He struggled with the fact that he didn’t look like either his Kenyan father or his white American mother. He mentioned that to cope with some of his issues and questions, he turned to negative outlets, such as drugs. It was unclear to him what he was, as my identity was unclear to me.

As I got older, things didn’t get clearer. My friends knew I was black. But, if they heard someone call me black, my friends, thinking they were standing up for me, would say, “No, she doesn’t act black or talk black. She is white, just like us.”

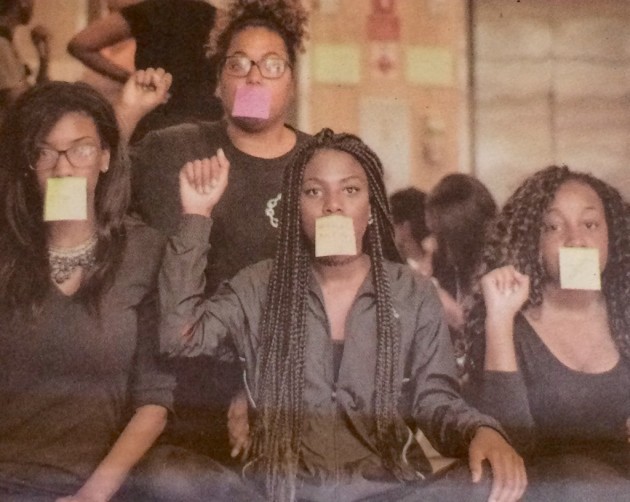

I would smile and agree with them, but it never felt right. In high school, I remember getting my hair braided and loving my new look. It made me feel strong and powerful, as if I was embracing a part of myself I never knew existed.

Yet that first day I walked through the halls of my school with my new braids, two boys yelled at me that cornrows belong in the fields, just like the ones beyond the school doors. It hurt me badly, and no matter how hard I try to forget that day, I can’t.

The old formula, “one drop of blood, you’re black,” held in Puyallup where the U.S. Census Bureau pegged the population at 38,000 with 2,000 people of those people claiming they belonged to two or more races.

Every day I would go home and wish to be white or pink, as I called it, like my mother.

Ultimately, I decided to leave Puyallup, a town that seemed blind to the rest of the world. I was accepted at Washington State University, a five-hour drive from home; Western, Washington , a shorter drive from home and at Howard University, clear across the country.

My high school counselor, one of the three or four black people at the school, suggested that I apply to Howard. He told me I should learn more about myself and where I come from other than what I knew about my mom’s side. My father endorsed the idea.

I enrolled in Howard University. My idea was to go somewhere where I wouldn’t feel that all eyes were on me every time I entered a room.

I was no longer the only black person in a room. But………

To my surprise, on freshman dormitory move-in day, I was again singled out, this time because of my light skin. I didn’t even know what that meant. I quickly learned that there was a division in the black community, too. Once again, I felt like I didn’t fit in, even at Howard. My new peers thought things came easier for me because of my lighter complexion, while in my old town I was singled out for being black.

Now I had a new layer of confusion.

Then I saw him. At the time, he was running to be the nominee of the Democratic Party for president. Barack Obama, a name that was unfamiliar to me, was about to speak at the Convention Center in downtown Washington, and my history professor was taking the class.

By the time we arrived, the room where Obama was to speak was filled. Security guards refused to let us enter. But a man who also wanted to get in distracted the guard, and as they argued, a girlfriend I sneaked into the room.

For the first time, I saw many kinds of people come together in awe of someone who was like me. He too came from a biracial family. I listened as the man inspired a room full of other people. Still, I felt he was talking directly to me.

Once I heard his speech, I was hooked on Obama, and because of him, I paid more attention to politics. The only hard part for me was taking this new attitude back to my home town. Both of my parents are Democrats, but my white grandparents, with whom I am extremely close, are hard-core Republicans, so much so, that on the refrigerator next to a picture of their grandkids was a Christmas card from the Bush family. Still, as I moved politically more towards Obama, it never affected the deep and warm affection between me and my white grandparents.

As I watched Obama’s campaign evolve, I felt the nation evolve. I was evolving, too. I felt a sense of hope, acceptance and tolerance begin to take hold, particularly after Obama became the Democratic nominee. That night, I hugged complete strangers. I high-fived a group of highly intoxicated people who were running down the street. I watched children and adults of all races and all backgrounds light sparklers and weave in and out through the stopped cars in the middle of a busy road. I witnessed my friends call their parents and grandparents and cry over the phone while repeating the words, “Yes, we can!” Through Obama and his campaign, I know what I am now. I no longer have doubts whether I fit in or not. We are all different and that’s the beauty of life. Obama opened my eyes and the eyes of many other Americans.

I am what Obama is. I am what every voter is.I am what every citizen is.I am an American.