Everyone fears something. Sometimes you see it at night while you’re trying to sleep. However, you find comfort in knowing that when you open your eyes again, you realize it was just a nightmare. But what if your most significant nightmare turned into your reality?

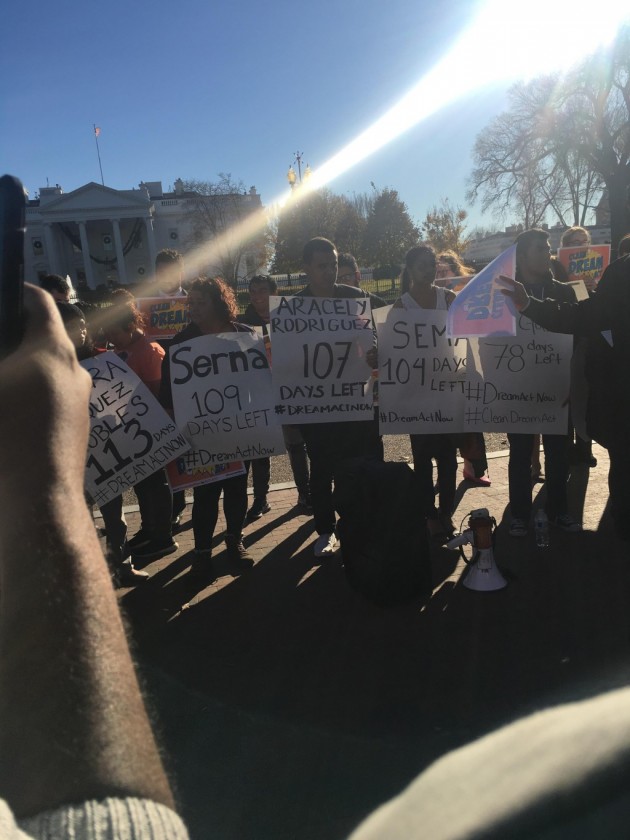

Many children under the Deferred Action For Childhood Arrivals (DACA) known as “Dreamers” are dealing with just that.

On Sept. 5, President Donald Trump announced the ending of an Obama-era program that protected thousands of undocumented immigrant children brought to the United States by their parents. For many of these undocumented young adults and children, America is the only home they know. In some cases, English is the only language they’re fluent in, and they fear the unknown.

However, the Dreamers do have an ounce of hope left in the hands of Congress. President Trump has given lawmakers six months to act before he takes things into his own hands. For Maria Mantilla of Washington, the end of DACA could change a lot. “I moved to America when I was six years old…I’m 31 years old now. I’ve been here for 25 years. This is all I know.”

Like most DACA recipients Mantilla has spent most of her life in the United States. Nearly 75 percent of DACA recipients are under the age of 25.

“I knew once the DACA orders came out that I’d be able to apply, I had just finished my first degree…and I’ve never committed a crime; I knew it would be a great opportunity for me,” she says.

According to the American Immigration Council, nearly 1,000 DACA recipients live in the District, and undocumented immigrants comprised 4.9 percent of the District’s workforce in 2014. A study by the Pew Research Center found that there are 25,000 undocumented immigrants living in D.C.

Throughout his presidency, President Trump has made many accusations against undocumented immigrants in America. He has called Mexicans crossing the borders "rapists," and said they were bringing drugs to the U.S. The Trump administration has taken an increasingly tough stance on legal and illegal immigration.

During the 2016 presidential campaign, Trump repeatedly led chants of "build the wall" at rallies, calling for a wall on the U.S. southern border with Mexico. His so-called "travel ban" — which bars nationals from six majority Muslim countries from entering the U.S. has been characterized as xenophobic. The Supreme Court on Dec. 4 allowed the third version of the travel ban to take effect.

However, Mantilla thinks differently. “There are people who are saying we’re taking jobs from people and we’re taking advantage of being here and not paying any cost…but every time I get a check or an advancement I have to pay taxes and social security, and I don’t get to see the benefits of that. I’m here because I love this country, I pledge allegiance to its flags and everything the country stands for if I could apply to become a full citizen, I would.”

Now a mother, Mantilla fears the overturn of DACA. “My daughter was born here and is an American citizen. If I were to have to go back to Mexico, it would be extremely hard on her and me…we’ve had the opportunity to visit Mexico to see my grandmother but two weeks is not like moving there," she says.

However, like her government nickname precedes her, Dreamer Mantilla is hopeful that this nightmare will soon be over. I have a good job here [in Washington DC]; my daughter is getting her education. It’s important that we stay here,” Mantilla stresses. “We aren’t bad people…its tough…there are people who don’t want us here. But we pledge to this country. For us, this is our home too.”