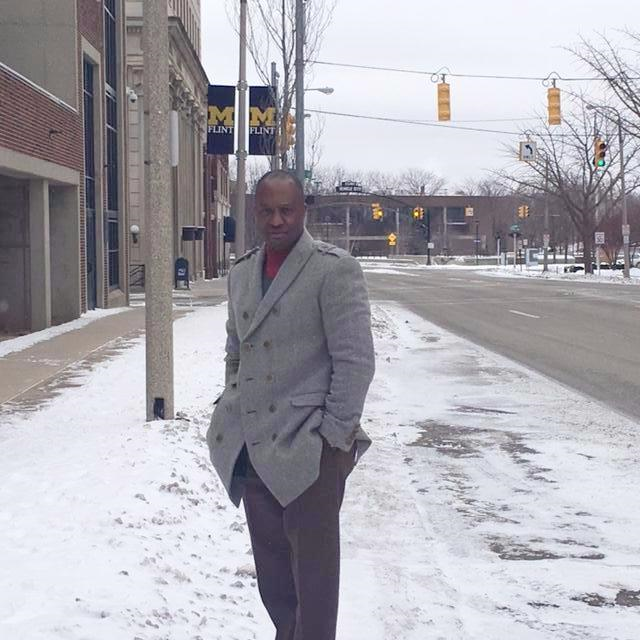

Black Chamber of Commerce President

U. S. Black Chamber President/CEO Ron Busby stands near the

Flint campus of theUniversity of Michigan,which he said was

working fine while black businesses suffered.

FLINT, Mich. — U. S. Black Chamber President/CEO Ron Busby stands near the Flint campus of the University of Michigan, which he said was working fine

while Black businesses suffered.

Ron Busby, president/CEO of the Washington, D.C.- based U.S. Black Chambers, Inc., has compared the Black-owned business community in Flint, Mich. to a “ghost town” amidst the city’s water crisis.

“If you visit Flint, it’s very noticeable that it’s the tail of two cities,” said Busby.

On a recent trip to assess the impact of the crisis on the Flint business community, Busby noticed that two colleges, University of Michigan, Flint Campus, and Mott

Community College were open and functioning normally through the water crisis while Black-owned businesses struggled.

“I was not able to speak with administration [of the colleges], but from my understanding, they made the changes necessary, early on in the conversation. So their issue has been corrected or at least addressed to the point where they are not facing the same challenges as other parts of the community,” said Busby.

Meanwhile, the Black business community “was almost a ghost town,” he said. “Many of them were either closed or didn’t have enough customers to open up for normal business hours.” Busby also noticed on his trip that the businesses and restaurants of downtown Flint were open and operating.

“If they’re getting clean, functioning water, where is the issue?” Busby said he asked himself. “Then you go to the communities of color, that’s where you see the biggest impact.”

According to Busby there was a cost associated with the necessary improvements. Therein lay the problem. Some businesses were able to take advantage of government support, he said, but others, “obviously, did not have the same opportunity.”

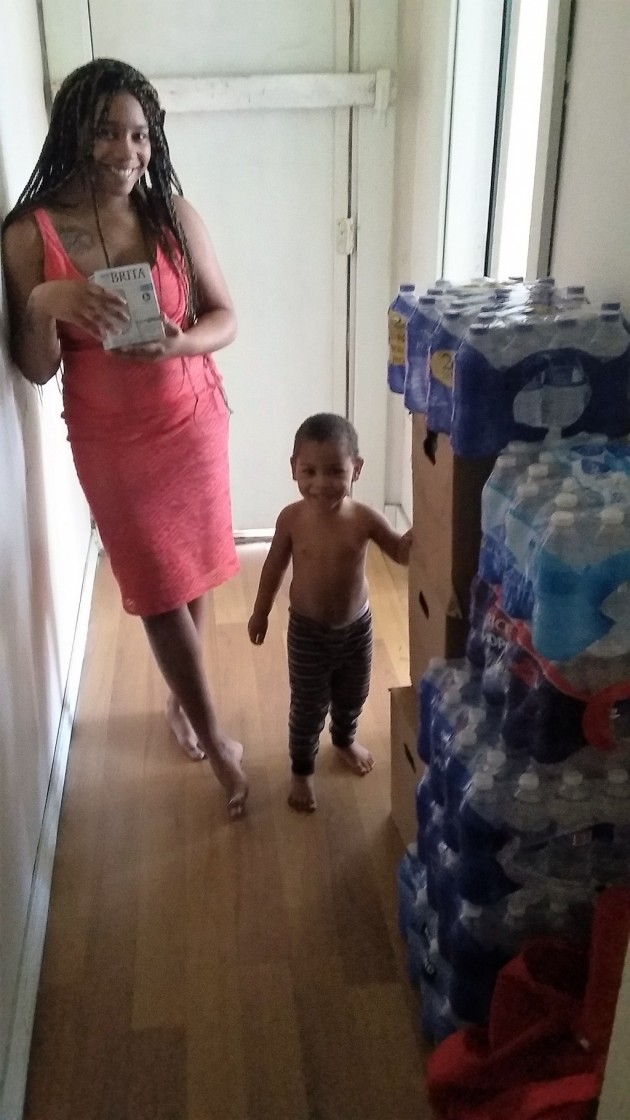

The tragedy in Flint, Mich. that began two years ago continues to unfold. In a nutshell, in April 2014, as a cost-cutting measure, Flint switched its water supply from Detroit’s water system to the Flint River. A group of doctors, led by Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha, urged the city to stop using Flint River as a water supply after high levels of lead were found in the blood of children.

Experts believe about 8,000 children were exposed to lead-contaminated water, according to the New York Times. The issue has now boiled into a national tragedy, drawing national media attention as well as the attention of political, civil rights and economic justice leaders. Most have resolved that the neglect was based on race.

According to the U.S. Census, more than half of Flint’s 99,000 residents are Black and 40 percent live below the poverty line. Historically, African-Americans were drawn to Flint to work for General Motors and other car factories. Flint was known for producing large quantities of vehicles earning it the nickname “Vehicle City.” Businesses opened in Flint to support the car production companies.

“When General Motors decided to leave, it left that city in an unfortunately almost bankrupt situation the day they made that decision,” said Busby. People were left in Flint without another source of income. Busby, whose USBC represents 250,000 small businesses, says Flint is the worst of tragedies, but racial disparities are widespread.

This “environmental racism” can be seen around the country, Busby notes. He said 75 percent of African-American businesses are located in areas that are hazardous or lack the ample amount of resources the business needs.

“Even with the snowstorm that hit Washington D.C. in January, businesses were addressed first in reference to snow removal, getting them back up. But it’s always going to be the communities of the majority that get the first resources. They get the most amount of dollars reinvested into their communities,” said Busby. “With our people, there are a lot of challenges forced upon them outside of our control, some of them being natural, some them being manmade.”

In a statement issued to the press after the Flint visit, Busby said, "We are saddened to see Black businesses and families suffer from the greed and mis-governance of local and state officials. Flint was once an epicenter of a thriving automotive industry which created wealth for the Black residents of Flint.

He concluded that the man-made crisis gives three “hard truths”: “Environmental racism is evident, the poisoning of Flint was entirely preventable and Poverty makes communities vulnerable to injustices. There must be a mass effort to increase wealth in the Black community through business ownership as a logical approach to alleviate vulnerability to injustices and man-made crises."