Greer Jackson, Howard University News Service

When the Mars rover Opportunity was retired by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration in 2019, 8 months after it was caught in a huge dust storm on the Red Planet’s surface, a sentimental interpretation of the robot’s final data dump went viral on social media: “My battery is low and it is getting dark.”

The rover, designed by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, was only supposed to carry out a 90-day mission to explore Mars’s surface for signs of past life. In a historic feat of modern science, “Oppy” drove on the planet’s surface for 14 years after it’s 2004 landing, fittingly ending it’s mission in “Perseverance Valley”. NASA called Opportunity’s work “one of the most successful and enduring feats of interplanetary exploration”.

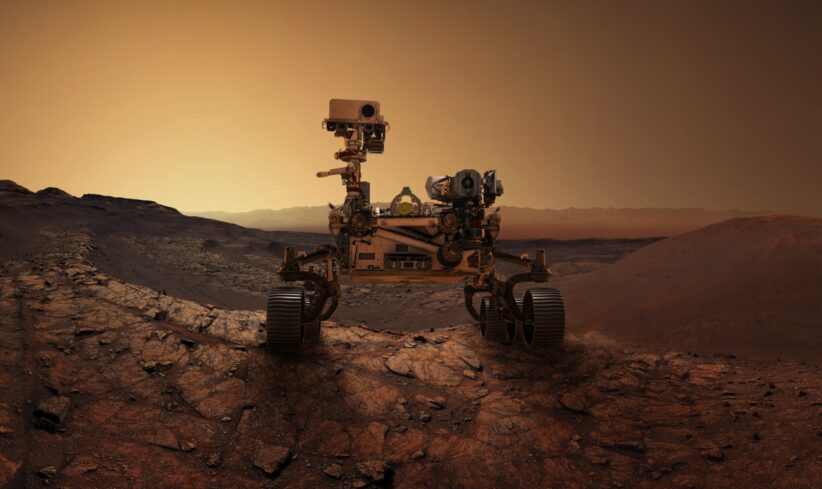

The latest milestone in this interplanetary journey has come to us in the form of NASA’s Perseverance rover, beginning, in name at least, where “Oppy” ended. On Feb 18. Perseverance became the fifth of NASA’s robotic vehicles to land on Mars, after a 7-month journey from the Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida. It joins its predecessors Sojourner, Spirit, and Opportunity, which have all ended their missions, as well as Curiosity, which is still active today. Video footage of Perseverance’s entry, descent and landing is unlike anything ever seen from that vantage point.

Mankind’s curiosity regarding the universe is reflected everywhere: space themes permeate everything from cinema and art to games and advertisements. For a long time, this curiosity has been the driving force behind space exploration.

“The space program satisfies the desire to compete, but in a safe and productive manner, rather than in a harmful one,” writes American physicist and aerospace engineer Michael Griffin in an Air & Space Magazine piece. “It speaks abundantly to our sense of human curiosity, of wonder and awe at the unknown. Who can watch people assembling the greatest engineering project in the history of mankind – the International Space Station – and not wonder at the ability of people to conceive and to execute the project?”

Perseverance’s mission represents another step in our quest to determine whether past life existed on Mars, as well as the viability of inhabiting the planet in the future – a quest that Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei probably only dreamed of when he made the first telescopic observation of the planet in 1610.

Since then, the idea of life existing on the planet has been questioned by laymen and scientists alike. In the late 19th century, when Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli observed the planet’s surface through his telescope, he began mapping and naming areas on Mars. Decades later, after several failed attempts by both U.S. and Soviet Missions, NASA’s Mariner 4 conducted the first successful flyby of the planet on July 14, 1965, capturing the first close-up image of the planet: a black and white depiction reminiscent of an ultrasound. In 1997, the Mars pathfinder, another U.S spacecraft, was the first to land a roving probe on the planet: little Sojourner.

Mars rovers, which are remotely controlled by scientists and engineers here on Earth, have been instrumental in telling us what we now know about this planet that was named after the Roman god of war: Curiosity, for example, found that ancient Mars had the right chemistry to support living microbes; “Oppy” has discovered signs of water once existing on the planet and has studied the formation of craters during its time on Mars. Scientists hope that Perseverance will continue this fact-finding mission.

“Perseverance is the first step in bringing back rock and regolith from Mars,” said Thomas Zurbuchen, NASA associate administrator for science, in a press release.” We don’t know what these pristine samples from Mars will tell us. But what they could tell us is monumental – including that life might have once existed beyond Earth.

According to NASA, the Mars Perseverance mission is the most sophisticated one yet. The 2,260 pound, 10 foot long rover is equipped with 19 cameras – more than any other before it- and travels with a companion: a helicopter named Ingenuity, which is the first aircraft to attempt powered, controlled flight on another planet. Perseverance also boasts pioneering technology such as the Mars Oxygen In-Situ Resource Utilization Experiment.

“The MOXIE instrument is a demonstration mission designed to prove that we can produce pure oxygen on the surface of Mars,” said NASA JPL engineer Jim Lewis, in a Youtube video. “If it’s successful, NASA may send a dedicated mission to produce oxygen for humans to use in the future.”

With Perseverance, NASA has also continued a tradition of adding a commemorative human touch to missions that are otherwise solely scientific. The rover was named by Alex Mather, an 8th grader from Fairfax, Virginia. It is fitted with a few special objects and messages, a practice that NASA calls ‘festooning.’ Some of the objects affixed to Perseverance’s body include a placard containing over 10.9 million names of people who participated in NASA’s “Send Your Name To Mars” campaign, as well as a COVID memorial plate which pays tribute to the perseverance of the world’s frontline workers.

“The Mars 2020 Perseverance mission embodies our nation’s spirit of persevering even in the most challenging of situations, inspiring, and advancing science and exploration,” said acting NASA administrator Stever Kurczyk. “The mission itself personifies the human ideal of persevering toward the future and will help us prepare for human exploration of the Red planet.”

Even though the U.S. came up against competition from the Soviet Union in the 20th century space race, it spends the most of any country on space exploration today, accounting for 30% of the operational spacecraft in orbit around the earth. In 2018, the government spent approximately $41 billion on space programs. In comparison, China followed with $5.83 billion, and Russia with $4.17 billion.

While there has been continued debate surrounding the value of spending billions of dollars on a sector whose findings may not benefit us as much as tangible solutions to social, economic and environmental issues here on Earth, some people believe that exploration is engrained in who we are- and this belief has spanned decades. Shortly before his death in 1996, Carl Sagan, one of the most influential planetary scientists to live, recorded a message for future explorers.

“Maybe we’re on Mars because we have to be, because there’s a deep nomadic impulse built into us by the evolutionary process — we come, after all, from hunter-gatherers, and for 99.9% of our tenure on Earth we’ve been wanderers,” he said. “And the next place to wander to is Mars. But whatever the reason you’re on Mars is, I’m glad you’re there. And I wish I was with you.”

With every successful rover landing, this message becomes more poignant.