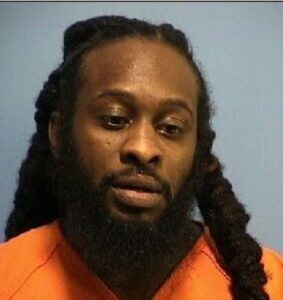

WASHINGTON (HUNS) — Damon Landor, a Rastafarian who took the Nazarite vow to grow his hair in locks, was moved to Raymond Laborde Correctional Center to serve the last three weeks of his sentence.

Landor brought proof of his religious accommodation at two prior facilities and a copy of the court ruling that Louisiana recognized this religious practice under the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act of 2000 (RLUIPA).

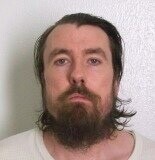

Landor presented these papers to a guard, who threw them in the trash and called in the prison’s warden, Marcus Myers.

Myers asked to see documentation of Landor’s religion, but Landor no longer had it.

Two guards carried Landor into another room, secured him to a chair with handcuffs and shaved his head.

Once Landor completed his sentence, he sued the Louisiana Department of Corrections (LA DOC), the prison, Myers and the department’s secretary, James LeBlanc, in their individual and official capacities for violating RLUIPA. Twenty-two parties including a range of religious groups, former correctional officers and the United States filed amicus briefs supporting Landor.

The U.S. Supreme Court heard oral arguments for Landor v. LA DOC on Monday to determine whether someone may sue government officials in their individual capacity for damages following RLUIPA violations.

The Louisiana Department of Corrections and Public Safety said the claims against officials’ individual capacity are barred. Zachary Tripp, Landor’s attorney, argued that RLUIPA clearly states damages are available.

Associate Justice Amy Coney Barrett said it was hard to see that this is clear, since the district court and 5th Circuit agreed with Myers and LeBlanc before an appeal brought the case to the Supreme Court.

According to Tripp, RLUIPA states that in the case of violations there will be appropriate relief against the government, which includes individuals acting under the state.

Joshua McDaniel, director of Harvard Law School’s Religious Freedom Clinic, which filed a brief in support of Landor, said Landor’s case against the employees in their official capacity will most likely be dismissed because of a previous Supreme Court ruling that barred suing a state as a sovereign entity and state authorities in their official capacity.

“I think no one can deny that this is a really egregious violation of the law and also an instance of prison guards thumbing their nose at a binding court precedent,” he said.

“What’s at stake in this case is when prison officials knowingly and blatantly violate what they know to be federal law, is there any remedy that the prisoner plaintiff has to have his rights under federal law vindicated?” – Joshua McDaniel

McDaniel added that because Landor is no longer in the prison, he cannot receive injunctive relief, such as getting a court order that forces the defendant to take some kind of action or to stop taking some type of action.

“So, the only remaining remedy that he could possibly get would be the individual capacity damages remedy,” he said.

McDaniel said the clinic sees this problem in nearly every case it litigates.

“I think it’s safe to say that in the vast majority of prisoner cases where there is a violation of their religious freedom, they would ultimately be left without a remedy under RLUIPA because the prisoners are frequently transferred or their claims are over and done with,” he said.

Steven McFarland, director of the Christian Legal Society’s Center for Law and Religious Freedom, agreed.

“If the warden and officers here are not individually liable for their grotesque violations of Mr. Landor’s rights, then the federal law that is at issue here is functionally toothless when it comes to people who are incarcerated,” McFarland said.

“So, if the state’s argument wins, then there is no remedy,” he explained. “Congress passed a law that has no teeth for when it comes to inmates. And that certainly cannot be the right, the correct ruling, the correct reading, the correct enforcement of an act of Congress.”

Benjamin Aguinaga, attorney representing the corrections department, argued that suing the respondents as individuals does not work to protect federal dollars, because officers aren’t direct recipients of federal funding and did not receive notice of liability.

To receive federal funding, state prisons agree to comply with RLUIPA. When the statute is violated, the federal government is not getting what it paid for, Tripp argued. He added that though the officers don’t directly receive federal funding, the state prison only acts through its officials.

Tripp said recipients of federal funds must follow RLUIPA and officials sign up for this when accepting the job. Some former correctional officials agree.

Daren Zhang, an associate at Kellogg, Hansen, Todd, Figel & Frederick PLLC, is a counsel of record for former correctional officials who worked in state prisons.

Zhang said support from former prison officials for Landor shows how egregious the religious violations are here and why the Supreme Court should rule that RLUIPA allows monetary damages against individual officials.

“They recognize that without this remedy essentially, a lot of the time, there’s no recourse,” he said. “The officials themselves recognize that it’s a powerful deterrent. It’s a necessary remedy, and they recognize the importance of it.”

In their amicus brief supporting Landor, Zhang and his colleagues state that correctional officials have all expected to be sued for money damages.

Chief Justice John Roberts said he doesn’t think that when prison guards are hired, they ask to see the agreements with federal law. In response, Tripp says officials in these facilities do receive training to comply with federal laws.

Reactions to Arguments

McDaniel said he noticed some skepticism from the justices considered to be more conservative and a sense of support from the liberal judges.

“There may be enough cracks in the conservative wing of the court that you might get at least two other justices to side with the liberal justices in the case to rule for Landor,” he said.

Meredith Holland Kessler, an attorney with the Notre Dame Law School of Religious Liberty Clinic, said she was not encouraged by the session.

“One can never predict just from questions,” Kessler said, “but it did seem like Justices Jackson, Sotomayor and Kagan were clearly supportive of Mr. Landor’s position, and it seemed like the other six conservative justices were having problems with it.”

However, Kessler added that it’s promising that the court was willing to hear the case especially with the decisions of the lower courts. This suggests that the Supreme Court may disagree with the previous decisions, she said.

The number of supporting parties on behalf of Landor is another source of hope for Kessler, she said. Her clinic filed briefs on behalf of the Jewish Coalition for Religious Liberty, a Christian community and a Muslim advocacy group.

What’s Next and Big Picture Implications

“If Mr. Landor wins, it means that people who are incarcerated will have some protection for their religious freedom rights as Congress intended,” McFarland said. “If Mr. Landor loses, then wardens and state prison officers can violate federal law with impunity, because they know they can’t be personally touched. They have no skin in the game.”

He added that he believes the officials clearly knew that they were violating federal law when they trashed Landor’s documents.

“If Mr. Landor doesn’t win … then inmates will not be able to expect this federal law to be enforced in state prisons,” McFarland said. “That’s a big deal — and especially when you know, where the purpose, supposedly, of imprisonment is rehabilitation, and we want to reduce prisoner recidivism or returning to prison.”

“This kind of lawlessness in a state prison, especially where Congress has tried to stop it, is certainly going to frustrate, the purposes of rehabilitation.”

Zhang believes this case also has the ability to fix an imbalance between federal and state prisons. If the court rules against Landor, state prison officials will not have a deterrence against breaking federal laws, while federal prison officials will continue to be subject to money damages, he said.

“Those state prisoners will continue to suffer from religious violation that have no recourse,” Zhang added. “That will, in practice, be the effect and that’s horrible. And then I think that’ll continue.”

If the court rules with Landor, Zhang said they would be equalizing the treatment in federal prison and state prisons. They would also be implementing a remedy that Congress intended when they passed the statute to protect religious freedom in state prisons.

“I have a client in 9th Circuit, who is waiting for this case, for his religious violations, just pending and then waiting for the right decision so that he could move his rule to put the case forward,” Zhang said.

Kessler said there are possibilities in which the court doesn’t just side with the petitioner or defendant.

The Supreme Court could possibly decide Congress didn’t say clearly enough that the statute authorizes monetary damages, she said. If that’s the reasoning, then that’s an invitation to Congress to respond with their intention.

“If the court’s reasoning is that regardless of how clear Congress was, they just don’t have the authority to do this, then that’s obviously a more frustrating outcome for folks like Mr. Landor, who otherwise won’t get relief,” Kessler continued. “But they do have options through state remedies as well and so it hopefully will lead to more robust protections at other levels.”

Damenica Ellis is a reporter for HUNewsService.com.

Why Do Inmates Get Their Hair Cut in Some Prisons?

Prisons typically argue that grooming policies — including shaving heads and beards of those who are incarcerated — are needed for security, according to Joshua McDaniel, an assistant clinical professor and director of Harvard Law School’s Religious Freedom Clinic

“They might be worried about contraband being hidden, or they might be worried about identification of prisoners,” McDaniel said. “If a prisoner were to suddenly change their appearance, then it might be hard to identify them.”

However, the Supreme Court has considered these arguments in Holt v. Hobbs, a 2015 case involving a Muslim prisoner, Gregory Holt aka Abdul Maalik Muhammad, who wished to grow a short beard. In this case, it was decided that the prison’s reasons for grooming policies didn’t overrule the religious freedom rights of a prisoner.

“When you have this conflict between prisoner religious freedom and prison policies, you have the prison obviously having an important governmental interest in having a safe and secure prison, but being very rigid and inflexible in how they enforce that,” McDaniel added.

— Damenica Ellis