Ahmari Anthony, Reimagined Futures for Howard University News Service

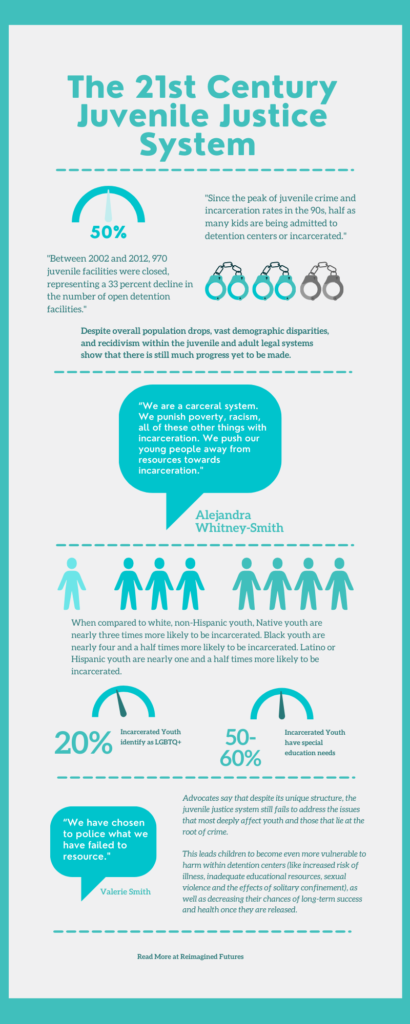

Since the peak of juvenile crime and incarceration rates in the ‘90s, half as many kids are being admitted to detention centers or incarcerated, reflecting the overall trend of drastic decreases in the number of justice system-involved youth.

The Annie E Casey Foundation’s Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative (JDAI) published their findings in the JDAI at 25 Report. Their insights showed a 49 percent decrease in juvenile detention facility admissions over the last quarter of a century. Additionally, 85 percent of juvenile detention facilities reported a lower detention population than 25 years ago. These facilities also reported committing 57 percent less youth to state custody each year.

Other organizations, such as The Sentencing Project, have reported even more staggering data. Their “Trends in U.S. Incarceration” Fact sheet said the number of youth committed to juvenile facilities has plummeted from about 75,000 in 1997 to just under 27,000 in 2017.

Additionally, between 2012 and 2002, 970 juvenile facilities were closed, representing a 33 percent decline in the number of open detention facilities.

“The hallmark of the juvenile justice system,” according to Marc Schindler, executive director at the Justice Policy Institute, “is that young people are amenable to change and there’s a great opportunity to work with them and get them on the right track. Historically, the juvenile justice system has focused on rehabilitation, on treatment, on confidentiality…and also that it’s individualized as much as possible. Those are quite different than the adult criminal justice system.”

With these numbers and those intentions, it would be easy to believe that these goals are being achieved. But despite the promising statistics and rapid transformation in the field, the changes are still leaving thousands of young people behind, failing to serve the purpose of the system and the needs of children and families.

Alejandra Whitney-Smith is a staff attorney at the School Justice Project, a legal services and advocacy organization that serves students involved in DC’s justice system who also have special education needs. She sees this disconnect in the mission of the juvenile system and the outcomes everyday in her work.

“Even though the language we use around the juvenile legal system is rehabilitative, it’s not. It’s punitive,” she says.

She points to recidivism rates as a glaring evidence of the system’s current failures.

“The reason why the juvenile legal system can be so harmful is because as soon as you touch it, we know from statistics that once you’re involved in the juvenile legal system, the chances of you being involved in the adult criminal legal system is ten times higher.”

Valerie Slater, the executive director of RISE for Youth, agrees, citing recidivism rates of nearly 70 percent in Virginia, where she works with and advocates for youth.

“We are better at passing kids from one system to another prison system than actually creating whole children, rehabilitating children,” she says. “It’s very frustrating that that’s our legacy.”

On paper, the public, the law, and children and families affected by youth incarceration all want the same thing: improvement.

According to a national poll on youth justice reform conducted by Youth First.“Americans overwhelmingly favor a youth justice system that focuses on prevention and rehabilitation (78 percent), while only 22 percent favor focusing on punishment and incarceration. The poll also finds that 62 percent of Americans favor closing youth prisons, up from 57 percent in 2019.” Support increased to nearly three-quarters when for-profit prisons are specifically mentioned.

Science also supports the rehabilitative goals of the juvenile system. Studies like ‘Brain Development in Adolescence’ have challenged commonly held ideas about delinquent and deviant behavior in the criminal justice field, asserting that “typically, adolescents seek diversion, new experiences, and strong emotions, sometimes putting their health at serious risk” and “reveal that a fundamental reorganization of the brain takes place in adolescence.”

Jennifer Ubiera, a Staff Attorney at the Georgetown Juvenile Justice Clinic, and advocate with Law for Black Lives DC, said the current rates of incarceration are of concern and the use of other punitive approaches (like family separation and court surveillance) should be replaced with truly rehabilitative practices and supports.

“If I’m telling you that someone’s brain is not all the way formed, you can’t think that that person is going to remain how they were as a child. They need the opportunity to grow and develop and get better,” she said.

The juvenile justice system is not really one entity, but instead a complex, variant process that utilizes a web of interconnected agencies that respond to youth accused of breaking the law. Only about half of juvenile cases are formally processed in court. Many young people are put on probation or monitoring systems, referred to the child welfare system. Juvenile records are also, generally, sealed at the age of 18.

However, there are still seven states (Georgia, Michigan, Missouri, New York, North Carolina, Texas, and Wisconsin) with state laws that allow children as young as age 16 to be funneled directly into the adult legal system or be saddled with decades-long sentences. These practices aid in the process of criminalizing youth and inhibit the potential for rehabilitation according to some experts.

Status offenses are another way that youth are uniquely targeted by the legal system. This category of offenses is unique because the acts are only considered criminal if you are a minor. It includes things such as running away, missing school (truancy), staying out too late (violating a curfew order), underage possession of drugs or alcohol, and being unable to be controlled by parents or guardians (ungovernability). These laws have disproportionately affected girls, trans, gender non-conforming, and other LGBTQ+ young people.

Both issues, indicative of what some experts say is the overcriminalization of youth, have been targeted by advocates, with much success to show for their campaigns. The Justice Policy Institute’s Raise the Age report says that between 2007 and 2017, the number of youth who were automatically excluded from the juvenile court system because of their age has dropped by almost half. Similarly, there are on-going campaigns to decriminalize status offenses in local and state jurisdictions across the country, aiding in producing the significant decreases in youth detention and state custody cases.

And young people are made vulnerable to being prosecuted on these youth-specific charges just by coming into contact with the court systems, which can happen for reasons that have nothing to do with their own actions, according to Ubiera. “A lot of times, these children are dual jacketed. And dual jacketed is that they had an initial abuse and neglect case and then got court-involved,” she said.

This is especially common for things such as status offenses. Children who run away from home are significantly more likely to have experienced severe abuse, according to the National Institute of Health, and are also more at risk to experience further abuse or other health-compromising behaviors.

Whitney-Smith said responding to these issues with legal repercussions reflects on youth and our society at-large.

“We are a carceral system. We punish poverty, racism, all of these other things with incarceration. We push our young people away from resources towards incarceration. And I’m talking about young Black and brown kids,” she said. “There’s this dehumanization of young kids of color that often occurs.”

Despite the implementation of legislative action and diversion programs in and outside of the court systems, data shows that youth of color are still disproportionately present in the juvenile justice system, despite overall changes.

The Prison Policy Initiative found that Black youth are nearly 4.4 times more likely to be confined than their white peers. (In some states, the rates can vary up to 10 times more likely.) Native American youth are 2.8 times more likely to be confined when compared to white youth, and Hispanic youth are nearly 1.4 times more likely.

In order to address the issues at the root of youth incarceration, advocates call for a new focus on accountability and investment, not isolation and punishment.

“Decarceration is not enough,” says Ubiera. “Decarceration tends to focus on the least of these: the misdemeanor, maybe the lower level felony. But no, children do not belong in cages. There is no justification for that. Even when a child has committed a heinous offense. The approach that we take to them should be rehabilitation, support, and finding ways to ensure that they can be held accountable without having to believe in a lack of self-worth.”

Individualized solutions focused on healing and development are also critical, according to experienced advocates. “Trauma needs to be addressed. And trauma needs to be addressed by the law and it needs to be addressed in policy. There is not enough being done, both research and practice, around the trauma that youth who are court-involved have,” said Ubiera.

According to the JDAI at 25 Report, demographic-specific solutions are also necessary to get to the root of the disparities that exist and persist currently within the juvenile justice system, even as admissions fall.

The Vera Institute’s Initiative to End Girls’ Incarceration seek to address the marginalization of girls in the juvenile justice system, while the School Justice Project is one of the only organizations that works with its specific population.

“Fifty to sixty percent of young people that are committed or involved in the systems have special education needs,” according to Whitney-Smith. “We also know that, especially with education related issues and special education, that the vast majority of young people that come in contact with the juvenile legal system have unmet needs somewhere else. Whether it be special education needs, whether it be a background of trauma, [or] mental health. These are the issues that need to be solved and the juvenile legal system is not equipped to solve them.”

LGBTQ+ youth are also overrepresented in the juvenile system, with up to 20 percent of incarcerated youth self-identifying as LGBTQ+, according to the Movement Advancement Project.

On the policy side, juvenile justice issues do not garner much attention from the federal government, especially over the past 4 years.

“There was really no significant progress and unfortunately, there was backtracking including not good implementation of the federal Juvenile Justice Delinquency and Prevention Act [and] reducing in funding,” said Schindler.

The Juvenile Justice Delinquency and Prevention Act incentivizes states to participate and protect incarcerated children in a variety of ways, like separating youth from adults in adult facilities, only placing youth in juvenile facilities, and enforcing the Prison Rape Elimination Act to protect youth from sexual violence. (According to the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, 7.1% of youth report being sexually victimized in a juvenile facility, with a vast majority of those kids having been victim to staff abuse or misconduct.)

Schindler says that “There was no good enforcement of those protections nor working with states to help them be in compliance and have good guidance on how to protect kids.”

Above all, advocates say that the answer is strengthening families and communities.

“If parents had resources to have food on the table, have childcare, all of these things that are really important to making a happy and healthy child, we could prevent a lot of the repeating cycles that we see,” said Whitney-Smith.

“We have chosen to police what we have failed to resource,” Valerie Slater said.

Ubiera agreed.

“Poverty is violent. Mariama Kaba quoted Danielle Sered and said ‘Nobody enters violence for the first time by committing it.’ If you think about that, we have young people like I’ve mentioned before who have committed heinous offenses or alleged to have committed heinous offenses, and their offense is looked at first. As opposed to what has happened, where they came from. That is only taken into consideration later. That doesn’t make sense.”