Hundreds brave cold, wind to honor former Mayor Marion Barry

Former Mayor Marion Barry was often spotted outside City Hall at Pennsylvania Avenue and 13½ Street where his office ersided. He is now honored there with an 8-foot-tall, bronze. Courtesy D.C. City Council

WASHINGTON—Marion Barry was different things to different people.

For more than 40 years, Barry was the best and worst of Washington, D.C., politics as a member of the school board and the City Council and as the controversial mayor of the nation’s capital for four terms.

He was a convicted crack cocaine user, an abrasive womanizer, but he was also a tenacious fighter for the rights and lives of African-Americans as a civil rights activist and the reigning politician in D.C. for a generation.

He was an abomination to some Washington residents and a hero to most.

Those who cherished their fallen champion gathered outside of City Hall in downtown of the nation’s capital on a cold, windy day this past weekend for another chance to honor the man a local newspaper dubbed “mayor for life,” a phrase that ultimately became his moniker.

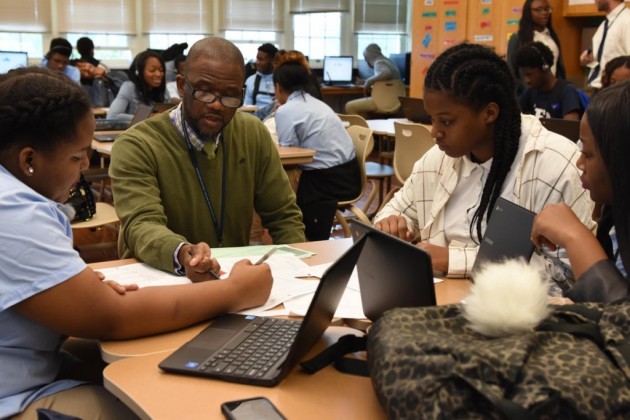

Hundreds came ouit on the cold, windy day to take photos of the statue

and to honor Barry's legacy as mayor, City Council member and activist.

Photo by Amiyah King, HU News Service

The city unveiled an 8-foot tall, bronze statue of Barry in front of the place that was his second home for so long. Barry died of heart disease in 2014 at age 77.

Hundreds, including residents of Ward 8 that Barry represented on the City Council for 15 years, filled the area at Pennsylvania Avenue and 13½ Street, the site of the statue. Many wore T-shirts and sweatshirts with Barry’s picture on them. D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser, all 13 City Council members, former city leaders and other personalities attended and gave speeches during a two-hour presentation.

Many praised Barry for his establishment of the Marion Barry Summer Youth Employment Program, which has provided thousands of jobs to high school students for over 35 years. They noted his other employment efforts that gave many Washington residents their first-ever jobs.

“He got my nieces and nephews their first jobs, so I would volunteer every time he ran for office,” said FIRST NAME Green, one of those gathered to honor Barry. “Nobody else, just him.”

They touted his battles with federal and city officials to make Washington more equitable for African Americans, who made up most of the city’s population during his tenure.

Bowser, a life-long resident of D.C.’s Ward 4, was a council member in Barry’s last days on the City Council after having grown up with him as the mayor. She talked about Barry’s influence on the city and her.

“His roots run long and deep across this country,” she said. “Uplifting people doesn’t just happen. You have to make it happen. Marion Barry made that happen for people all over Washington.

“In the last days of his life, he passed on all the knowledge he had to me. Now he wants us to grow with the needs of his city.”

In between speeches, the crowd chanted Barry’s name as fierce winds whipped through the celebration.

“Barry! Barry! Barry!”

Rock Newman, host of the popular radio program, The Rock Newman Show, and for 30 years one of the nation’s biggest boxing promoters, shared his love for the former mayor.

“Why do we love him?” Newman asked the crowd rhetorically, “because of his undying and quintessential dedication to service.”

Council chairman Phil Mendleson emphasized the symbolic and historical importance of the statue.

“There are no statues commemorating African Americans on Pennsylvania Avenue,” he said. “This is the first.”

D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowserr, second from right, talked herrelationship

with Barry as memberes of the City Council and his impact on the city.

Photo by Amiyah King, HU News Service

Even as speaker after speaker praised Barry, many who were not there, particularly white America, remember him differently.

To them he was the D.C. mayor videotaped smoking crack cocaine. He was ultimately arrested by the F.B.I. and convicted and sentenced to prison on drug charges.

To them, he was the city councilman who pleaded guilty to drug crimes and tax evasion and sentenced to probation after a mandatory drug test during an IRS investigation found cocaine and marijuana in Barry’s.

He was a scofflaw, who was being constantly arrested or hauled into court for a plethora of issues, thousands of dollars in parking tickets, driving while intoxicated, tax evasion.

He was the corrupt politician with so many shady dealings that in is waning years his fellow City Council members unanimously voted to strip Barry of all committee assignments, in essence making him politically powerless.

To most of the city’s African-American residents, however, he was the man who brought his years of civil rights activism with the NAACP and as first chairman of the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee into their city and later the mayor’s office. While mayor, they say, he unabashedly spent years uplifting black residents up by cutting them in on their share of the economic pie and righting the wrongs they had endured for years.

The city’s black residents had known Barry long before he became mayor. In 1967, he co-founded Pride, Inc., a Department of Labor-funded program to provide job training to unemployed black men, and provided jobs to hundreds of teenagers to clean littered streets and alleys in the district.

Current and former political leaders, Ward 8 residents, media and others crowd around the statue to get selfies and candids. Photo by Amiyah King, HU News Service

After the riots following the assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968, Barry created a program with Giant Food supermarket to distribute free food to poor black residents whose homes and neighborhoods had been destroyed in the rioting.

He also became a board member of the city's Economic Development Committee, helping to route federal funds and venture capital to black-owned businesses that were struggling to recover from the riots

In the 1970s, he was elected to the Board of Education later to the City Council, where he was immediately voted by other members as chairman.

Barry began his term as DC mayor in 1978. His first four Barry's first four years in office were characterized by increased efficiency in city administration and government services. He instituted his signature summer jobs program. Barry insisting that any firm wishing to do business with the city have minority partners, created legislation requiring 35 percent of all city contracts to go to minority-owned firms.

Later, Barry's combatted unemployment by creating government jobs. The city government's payrolls swelled so greatly that by1986, nobody in the administration knew exactly how many employees it had.

By his third term, speculations of drug use and domestic abuse swarmed Barry’s administration. Ultimately, they proved his downfall, and he was sentenced to six months in prison. Undeterred, Barry ran for City Council after he was released and won in 1992. His slogan read “"He may not be perfect, but he's perfect for D.C.”

Barry was re-elected mayor two years later, and served from 1995 to 1999. After his final term, Barry was elected repeatedly by Ward 8 residents to the City Council until his death.

Ronnell Barnes, who works in hospitality at a D.C. hotel said what a lot of people in the crowd felt and many in the city still feel about Barry.

“Regardless of if he did crack, he was the best mayor the city ever had for black people,” Barnes said. “He was our mayor when whites didn’t care…You’d have to be a Washingtonian to understand what I’m saying.”

.